What happens when a Muslim woman says no to the forced hijab?

What if that woman is not a secular activist or a Western journalist, but a religious scholar, a poet, and a former member of the Iranian Islamic parliament?

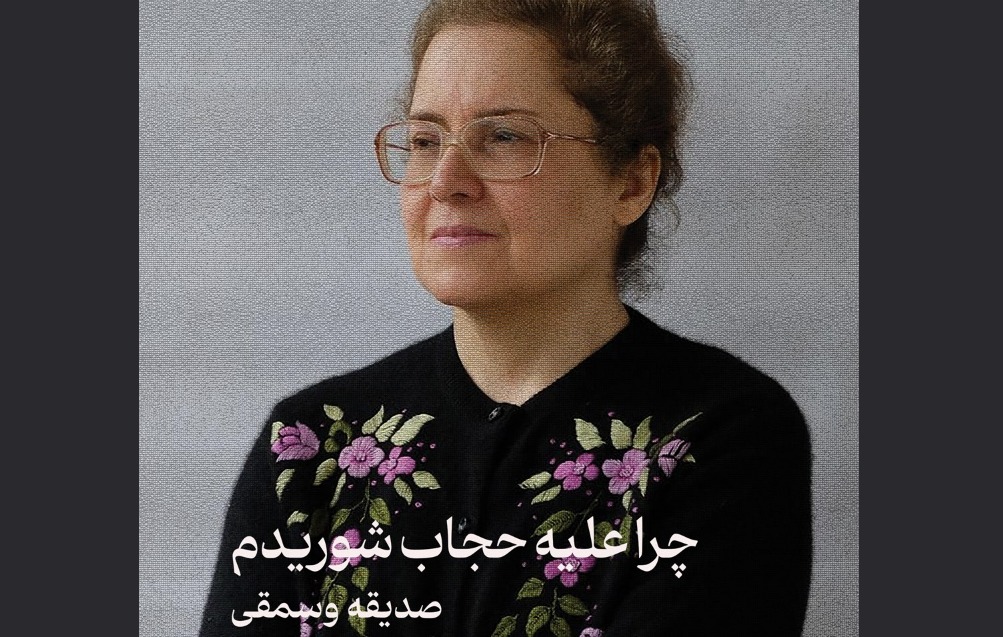

This article introduces a Persian-language book by Sedigheh Vasmaghi, a theologian, poet, and former Iranian parliamentarian who publicly removed her hijab in protest against the Islamic Republic. Her memoir, Why I Rebelled Against Hijab, is both a personal and political text that speaks from within the Islamic tradition—against the misuse of religion for authoritarian control.

But this is not just a book review. It is a call to recognize that inside Iran—and across the Middle East—there is a living, internal struggle over truth, freedom, and justice. These struggles are often silenced by the state or distorted by external narratives. They are not dictated by the West, nor are they symptoms of cultural betrayal. They are the work of individuals, often women, who engage critically with their own histories, beliefs, and communities.

Sedigheh Vasmaghi is not alone. In Egypt, Nawal El Saadawi challenged both patriarchy and state repression through decades of writing. In Lebanon, Joumana Haddad has used poetry and publishing to question gender, religion, and nationalism. Across the Kurdish regions of Iraq, Syria, and Turkey, women like Sakine Cansız helped build revolutionary movements rooted in gender equality.

These women—and many others—are part of a historical process: an intellectual and cultural evolution that can be compared, in some ways, to the European Renaissance. But this renaissance is not happening in peace. It is unfolding under surveillance, prison walls, torture, and constant threat. It is shaped by internal state repression, regional authoritarianism, and geopolitical confrontations that treat human lives as bargaining chips.

Vasmaghi’s book is a document of this evolution. It is not a plea for Western intervention. It is a demand that we, as readers—especially in Europe—listen without projecting our own cultural fantasies or Cold War binaries. The debates inside Iran are not East vs. West. They are struggles over dignity, freedom, and ethical life. They come from inside the society and deserve to be read with seriousness and respect.

What would happen if we treated voices like Vasmaghi’s not as exceptions, but as the beginning of a new tradition?

A Voice from Inside the System

Sedigheh Vasmaghi is not an outsider to religion or Iranian society. She studied Islamic theology, taught at the University of Tehran, and served as a member of the Iranian parliament during the reformist period. Her book Why I Rebelled Against Hijab shows that her fight against forced hijab does not come from rejection of Islam—but from deep belief in justice, freedom, and rational thinking inside religion.

In the first chapter, titled “The Path I Took to Remove My Headscarf”, Vasmaghi writes about her upbringing in a religious family. Her father, a traditional but open-minded man, taught her to think independently and never accept humiliation. She grew up with love for books and questions. Even as a young girl, she asked why women must cover their hair if the Quran does not clearly say so.

Her early decision to study Islamic law was not to become a preacher, but to search for answers. She writes that she was not satisfied with simple rules. She wanted to understand the meaning behind them. Over time, this search led her to a painful but clear conclusion: the command to wear hijab is not a divine order, but a human interpretation, shaped by politics and patriarchy.

Vasmaghi writes honestly about her own contradictions. For many years, she wore the headscarf—even while doubting it. She hoped that change would come without personal risk. But eventually, she realized that silence meant agreeing with injustice. So she took a stand.

From Research to Rebellion

For many years, Vasmaghi tried to work inside the system. She was a religious scholar who believed in reform. She respected faith but criticized how religious authorities used it to control women. In her academic work, she began to question the legal foundations of hijab. Why did clerics say it was mandatory? Was there real evidence in the Quran? Were the traditions (hadiths) reliable? Step by step, her research showed that forced hijab had no clear basis in Islamic law.

In the chapter “A Brief History of My Changing Thoughts About Hijab”, Vasmaghi explains how the word hijab in the Quran does not mean headscarf. It simply means a curtain or a barrier. The Quran never says that women must cover their hair. She also shows how early Muslim communities did not apply the strict dress codes we see today in countries like Iran or Afghanistan.

But the problem was not only religious interpretation. It was political. After the 1979 revolution in Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini promised freedom. He said women could dress as they wished. But soon after taking power, the regime made hijab compulsory. Vasmaghi writes that this was not a religious act—it was a tool to control and silence women.

In one of the most powerful theological sections of the book, she explains clearly: the Quran never states that women must cover their hair. The verses often used to support hijab laws refer to general modesty, and the Arabic words from Quran which clerics translate as “veil” or “scarf”, are open to different interpretations. These are not divine instructions. They are cultural interpretations that became legal obligations through political enforcement.

She further shows that early Muslim communities were not uniform in their dress. Many of the Prophet’s early followers came from tribal or nomadic cultures in the Arabian desert. They were often semi-naked, and there is no evidence that the Prophet ever forced women—or men—to adopt specific clothing. Covering the body was understood as a social custom, not a religious law.

This argument is not just academic. It directly challenges the ideological foundation of the Islamic Republic’s hijab laws. By showing that the veil is not a religious obligation but a cultural imposition turned into law, Vasmaghi removes the theological shield used by the regime to justify its violence against women.

By combining academic argument and personal experience, Vasmaghi’s book becomes more than a protest. It is a call for Islamic reform and legal honesty. She wants Muslim societies to separate belief from coercion, and faith from authoritarianism.

Your support helps keep this space alive but also ensures that these critical discussions remain accessible to all.

Jina/Mahsa Amini and the Turning Point

The murder of Jina/Mahsa Amini in September 2022 changed everything for Sedigheh Vasmaghi—just as it did for millions in Iran. Mahsa, a 22-year-old Kurdish woman, was arrested in Tehran by the “morality police” for allegedly wearing her hijab “improperly.” After a few hours in custody, she was dead. Her death sparked the biggest protests Iran had seen in decades. And for Vasmaghi, it broke the last barrier of fear.

In the chapter “Mahsa Amini’s Death: The End of Hijab in the Islamic Republic”, she describes how this tragedy gave her the final push to act. She publicly removed her own hijab and began speaking out, not only as a scholar, but as a witness. She joined mourning ceremonies, stood beside grieving families like those of Armita Geravand, and used her voice to condemn the violence done in the name of religion.

Removing her hijab was not just a symbolic act—it was a political declaration. In a chapter titled “The Path of No Return”, she writes: “You cannot dress a religious command in the clothes of law.” For her, forced hijab is not law, but religious authoritarianism pretending to be law.

Before her arrest, Sedigheh Vasmaghi had already faced another kind of confrontation—one that symbolized the Islamic Republic’s deep fear of educated, independent women: the classroom.

In a striking episode described in the middle of the book, Vasmaghi recounts how a senior cleric—who had no academic qualifications but held institutional power—entered the university classroom where she taught and tried to take over her course. Without warning or discussion, he sat in her chair and told the students she had “withdrawn” from teaching. It was a lie.

This was not just about one class. It was about control. The cleric believed that being a man, a mullah, and loyal to the regime gave him more right to teach—even though Vasmaghi held a doctorate in Islamic jurisprudence and had years of experience. It was a clear attempt to silence her, erase her authority, and assert the dominance of male religious figures over female intellectuals.

But Vasmaghi did not accept it.

She publicly challenged the cleric, informed her students, filed a complaint with the university, and refused to be removed. She writes that some of her female colleagues were too afraid to support her. But she pushed back—alone if necessary—because, as she says, “This was not just about me. It was about women’s right to exist and speak in spaces of knowledge.”

Her open letters to Iran’s Supreme Leader and her speeches at memorials made her a target. She was arrested, interrogated, and jailed in Evin prison. But even in prison, she did not stop. She continued to write, to argue, and to resist.

This part of the book shows the power of women who transform grief into resistance. Vasmaghi’s rebellion is not against faith—it is against fear.

Prison and the Price of Dissent

In the chapter titled “In the Prison of Tyranny”, Sedigheh Vasmaghi gives a detailed account of her arrest, interrogation, and months of imprisonment in Tehran’s notorious Evin prison. She writes not to complain, but to document what happens to women who speak the truth in Iran.

Her crime? Writing about the hijab. Attending a memorial. Saying openly that religion should not be used to punish. For this, she was taken from her home, denied legal rights, and placed among other political prisoners. In prison, she met women from different walks of life: students, workers, activists, mothers—all imprisoned for their opinions, protests, or even for simply choosing how to dress.

One powerful moment comes when she recalls a fellow prisoner’s last words to her as she was released: “Be our voice.” That sentence echoes throughout the book. Vasmaghi sees her writing as a form of solidarity—not only with women like JIna/Mahsa Amini, but with all Iranian women who are punished for thinking freely.

She also shows how religion is used inside prison to justify cruelty. Guards quote religious texts while denying medical care, or separating mothers from their children. For Vasmaghi, this is the deepest betrayal of faith.

Yet, despite the suffering, her voice remains calm, determined, and full of purpose. The prison chapters reveal a truth that goes beyond Iran: that authoritarian regimes often fear women the most—especially when those women speak from inside the tradition they are trying to control.

A Call to Rethink Faith and Freedom

In the final part of Why I Rebelled Against Hijab, Sedigheh Vasmaghi brings her reflections together in a direct appeal—not only to the Iranian regime, but to the wider Muslim world. She asks a simple but serious question: If God did not order the hijab, who gave people the right to force it on women?

Her answer is clear. The hijab, as enforced by the Islamic Republic, is not a religious duty—it is a political weapon. It is used to control women, limit their public presence, and suppress their voice. For Vasmaghi, the deeper problem is that many Muslim societies have allowed power-hungry clerics to speak in the name of God.

She does not call for an end to religion. On the contrary, she insists that faith can survive only if it respects human dignity. She argues that Islamic law (sharia) must be based on ethics and reason—not fear and punishment. Women should be equal in rights and responsibilities, not treated as passive bodies to be covered and controlled.

In the chapter “Why I Rebelled Against Hijab”, she writes with honesty and courage about the cost of change. She knows that many Muslim women still feel pressured—by family, by society, or by fear. But she tells them: “You have the right to ask. You have the right to choose.”

This book is not just for Iranian readers. It speaks to anyone who wants to understand how women are fighting back—not only against dictatorships, but also against the misuse of religion. Vasmaghi shows that rebellion can come from inside the tradition, and that real change begins with truth-telling.

Vasmaghi writes:“Since hijab has long been presented in our society as a religious and Sharia-based obligation, I believe that’s precisely why many people have avoided commenting on it or have been cautious about discussing it. Still, I think the role of religious reformists in opening up space for debate has been fundamental and foundational. Of course, many factors have contributed to this issue, and one of the most important has been women themselves—women who have always opposed compulsory hijab, resisted it, and never accepted it.

But because the hijab was framed as a religious matter, many political figures may not have seen themselves as qualified to intervene. Religious reformists, however, stepped into this debate effectively and played a deeply influential, structural role. Even when others took action, we can say that religious reform paved the ground for those efforts.”

Rebellion from Within

Vasmaghi is also the author of a jurisprudential book on women’s issues. “Woman, Fiqh, Islam” is a legal, theological, and social examination of women’s rights. In this book, she critically analyzes the views of certain Islamic jurists and their methods of deriving legal rulings. Topics such as polygamy, a woman’s right to leave the house, sexual autonomy, male authority over women, maternal rights and responsibilities, custody, maternal guardianship, divorce, age of maturity, women’s eligibility for judgeship, testimony, blood money, and inheritance are all scrutinized.

The author challenges the attribution of these rulings to Islam, arguing that they are based on cultural customs rather than divine law. She believes that legislation—including civil and criminal law—should not be treated as religious rulings unless they clearly contradict basic Islamic obligations or prohibitions.

Why I Rebelled Against Hijab is not just a memoir. It is a statement of political resistance, religious courage, and intellectual honesty. Sedigheh Vasmaghi is not an outsider to Islam or Iranian culture—she is a woman who lived within both, and now dares to challenge their abuses from within.

Sedigheh Vasmaghi formulates her critique from within Islamic history and jurisprudence—not from a position outside the tradition. Her challenge to the forced hijab and to gender-based legal discrimination is rooted in deep scholarly engagement with classical Islamic texts, legal methods (usul al-fiqh), and the lived realities of early Muslim societies.

For Vasmaghi, the concept of the Muslim woman is not a fixed cultural stereotype defined by veiling or obedience. It is not a matter of outward appearance or social behavior. Instead, she sees it as a subject shaped by interpretation, law, ethics, and agency. Her work insists that being a Muslim woman should not mean being reduced to symbols like the hijab. Rather, it should mean having the right to think, speak, interpret, and live with dignity.

In this way, Vasmaghi reclaims both Islamic knowledge and female subjectivity from the grip of authoritarian and patriarchal power, refusing to allow either theology or culture to erase women’s freedom of conscience.

Her book is a rare example of how personal experience, legal knowledge, and faith can come together in the fight for freedom. She does not ask readers to abandon religion. She asks them to question authority. She reminds us that even in the darkest places—in courtrooms, in prison cells, in religious schools—there are people still thinking, still resisting, still believing in justice.

For readers in Europe, and especially in Greece, this book offers an important lesson: Muslim women are not silent victims or simple symbols. They are thinkers, leaders, and rebels in their own right. Their struggle for dignity is not only a local fight—it is a global conversation about freedom, faith, and the meaning of equality.