In late July, a political gathering took place in Munich that brought together a wide range of Iranian right-wing opposition figures in exile under title of “National Cooperation to Save Iran.” On the surface, it looked like another conference of activists and politicians trying to present themselves as an alternative to the Islamic Republic. Yet, behind the stage lights, national flags, and emotional speeches, it revealed a great deal about the internal politics, power ambitions, and strategic weaknesses of the Iranian opposition abroad.

The event was organised around the presence of Reza Pahlavi, the son of Iran’s last monarch before the 1979 revolution. For his supporters, Pahlavi is more than a political figure — he is a symbol of Iran’s pre-revolutionary state, a living link to a period they see as one of national pride and prosperity. For others in the opposition, his role is more controversial. He has no official political mandate, but his name and family history give him a public profile few other Iranian exiles can match.

This conference was not just about giving speeches. It was a performance aimed at projecting unity, leadership, and a roadmap for Iran’s future. However, when examined closely, it also revealed deep contradictions, controlled messaging, and a reliance on symbolic gestures over detailed political planning. For observers outside Iran, understanding the dynamics of this event is important — not because it signals an immediate political change inside the country, but because it shows how exiled political forces imagine themselves as the future rulers of Iran, and how their strategies might repeat the mistakes of the past.

Your support helps keep this space alive but also ensures that these critical discussions remain accessible to all.

The Event: Setting and Atmosphere

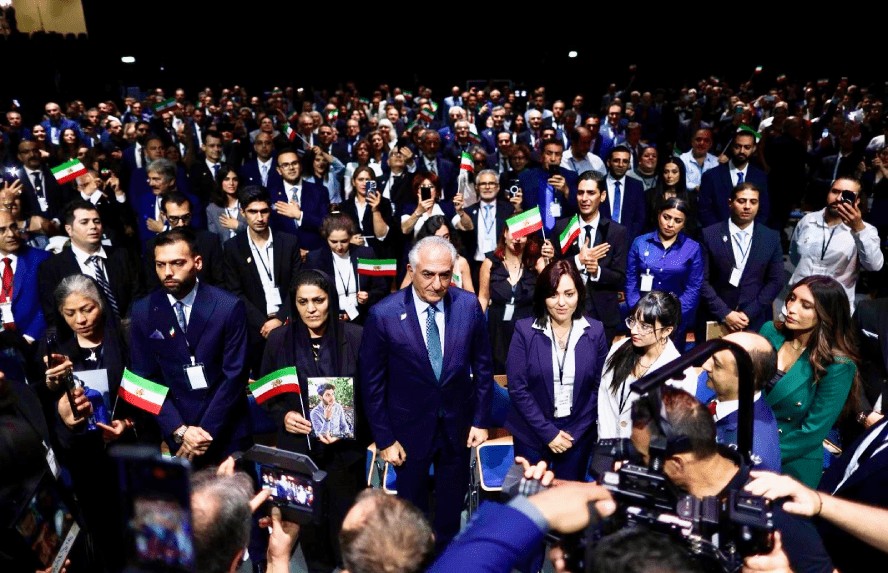

The Munich conference was designed to look like a historic moment for the Iranian opposition. The hall was decorated with national flags, traditional clothing from different regions of Iran, and large images recalling both the monarchy’s past and a vision of a bright future. Attendees came from across Europe, North America, and even Australia to be part of the gathering.

From the start, the atmosphere was highly emotional. Supporters waved flags, some bowed or kneeled before Reza Pahlavi, and others kissed the ground or the royal flag. Elderly attendees, including an 87-year-old woman whose family had been victims of the Islamic Republic’s repression, delivered heartfelt statements in defence of Pahlavi. These personal displays were met with loud applause, turning the event into a mixture of political rally and nostalgic reunion.

The emotional tone often overshadowed political discussion. Slogans such as “Javid Shah” (“Long live the Shah”) were chanted, though at times organisers discouraged certain slogans, possibly to keep the message broad and inclusive. The audience was a mix of monarchists, ex-reformists, and former members of Iran’s security forces, all sharing the stage but not necessarily a shared political programme.

Visually and emotionally, the conference succeeded in showing a united right-wing front. Politically, however, the event relied heavily on symbolism and ceremony, with little evidence of open debate or disagreement. The stage was carefully controlled, and the feeling of spontaneity came mostly from the audience, not from the speakers or the structure of the programme. This balance between spectacle and politics became a defining feature of the day.

Who Spoke and How They Were Chosen

The conference featured around 72 speakers, a mix of political activists, former officials, community figures, and a few representatives from minority groups. While the variety of faces suggested diversity, the selection process appeared far from open. Reports from some invited groups claimed that they were asked to submit the text of their speeches in advance, and in certain cases, those texts were rejected if they did not align with the organisers’ vision. One organisation even withdrew from the event after its proposed speech was declined.

The result was a stage filled with voices that followed a remarkably similar pattern. Many speeches opened with the same phrases about Iran’s current crisis, its “lost greatness,” and the hope for a prosperous future under new leadership. Historical references to the monarchy, the Achaemenid Empire, and ancient Persian glory were common. This repetition gave the impression of a central script rather than independent contributions.

Notably, several important political subjects were absent or barely addressed. Issues like labour rights, independent unions, social justice, and the role of grassroots organisations in a democratic future were missing. Women’s rights were mentioned only briefly, with the exception of a representative from the LGBT community who addressed discriminatory laws such as compulsory hijab. The lack of broader social and economic discussions suggested that the event’s organisers prioritised unity around Pahlavi’s leadership over open debate on the full spectrum of Iran’s political challenges.

For an event marketed as a national gathering, the narrow control over messaging raised questions about inclusivity and whether dissenting voices had any space on that stage.

Reza Pahlavi’s Speech: The Public Message

Reza Pahlavi’s speech was the central moment of the conference and was presented as a vision for Iran’s future. He began by thanking attendees for their trust and affection, referring to himself not with a political title but as a “father” to the nation. In a patriarchal political culture, this language carries both emotional appeal and political weight — it frames leadership as a form of guardianship, where authority is personal and obedience is expected.

Pahlavi spoke of unity between monarchists, republicans, leftists, and other political tendencies, emphasising the need for a common goal rather than focusing on past differences. He painted an image of a free, democratic Iran where citizens enjoy equality regardless of religion, ethnicity, or gender. Yet these commitments were expressed in broad, optimistic terms, without concrete steps on how to achieve them.

One notable feature of the speech was his indirect way of addressing sensitive geopolitical topics. While discussing recent conflicts, Pahlavi referred to a “smaller country” that had taken control of Iran’s skies — widely understood to mean Israel — but avoided naming it directly. This careful wording seemed designed to avoid controversy among different supporters and international partners.

The speech was accompanied by nostalgic references to Iran’s “lost greatness,” with reminders of the Pahlavi era’s prosperity and modernisation projects. These images were reinforced by visual presentations and videos showing the royal family’s past. Overall, the public message was one of optimism, unity, and leadership — but also one that relied on symbolism and general promises rather than detailed political planning.

The Censored Segment: What Was Removed

Shortly after the conference, the official recording of Reza Pahlavi’s speech was edited, and a particular section disappeared from the version uploaded online. This removed part contained some of his strongest statements about the Islamic Republic’s leadership and internal divisions.

In the censored segment, Pahlavi claimed that many within Iran’s Revolutionary Guards were waiting for the right moment to abandon the regime, describing the Islamic Republic as a “sinking ship.” He addressed Ali Khamenei directly, warning that most people around him hated him and that the nation’s anger would eventually explode. He also invited members of the regime, including security officials, to “return” to the people — a call that critics saw as politically dangerous, suggesting reconciliation with figures who had been involved in repression.

Another key point in the removed section was his promise that even Khamenei would receive a fair trial under international legal standards. This contrasted sharply with the more aggressive rhetoric from some of Pahlavi’s supporters, who openly called for executions. The idea of a trial for Khamenei might have upset hardline monarchists, while also creating concerns for international allies about the tone of justice after a regime change.

The decision to remove this segment raised questions about image control and the balancing act Pahlavi’s team faces — trying to appeal to a wide range of supporters while avoiding statements that could alienate either domestic sympathisers or foreign backers. It also highlighted how even within an opposition movement, messaging can be tightly managed and selectively presented to the public.

The Transition Plan: Temporary Government and National Uprising Body

A central part of Reza Pahlavi’s speech was his outline for a political transition after the fall of the Islamic Republic. He proposed the creation of two institutions that would operate before Iran’s first free elections: a “temporary executive team” and a “national uprising body.”

The temporary executive team would serve as an interim government, managing the country during the transition. The national uprising body would act as both a strategic advisory group and a temporary legislative authority until a new parliament was elected. In other words, it would have the power to make laws and oversee political processes during this period.

However, Pahlavi gave no clear explanation of how the members of these bodies would be chosen, who would have the authority to select them, or how they would be accountable to the public. The lack of detail on selection and oversight suggested that these institutions could be formed entirely by his inner circle or trusted allies.

This plan carries strong echoes of Iran’s 1979 revolution, when Ayatollah Khomeini established a Revolutionary Council alongside a provisional government. That dual structure led to power struggles, with unelected bodies having significant influence over the country’s future. For critics, Pahlavi’s proposal risks repeating this pattern: creating powerful, unelected structures that could decide Iran’s fate without direct participation from the population.

The absence of mechanisms for transparency, democratic input, or protection against political monopolies makes this transition plan one of the most controversial elements of his speech — especially for those who believe a post-Islamic Republic Iran must avoid the centralisation of power that has shaped its modern history.

Political Messaging and Symbolism

Much of the conference’s power came not from its political content, but from its emotional and symbolic presentation. The event was saturated with nostalgia for the Pahlavi monarchy and for earlier periods of perceived national glory. Visual displays included historical footage of the royal family, images of grand state ceremonies, and scenes of prosperity from pre-1979 Iran. These were paired with futuristic, digitally produced videos portraying a modern and wealthy Iran under new leadership.

The stage performances reinforced this imagery. Attendees wore traditional Kurdish, Balochi, or Bakhtiari clothing, symbolising a united nation of diverse cultures. Some speakers referred to the greatness of ancient Persia, linking that heritage to the Pahlavi dynasty’s legacy. Elderly supporters expressed their loyalty through deeply personal gestures, such as bowing or kneeling before Pahlavi, which were met with loud applause.

At the same time, the political messaging was cautious. While the idea of national unity was repeatedly stressed, specific issues such as workers’ rights, democratic accountability, or the role of grassroots movements received little attention. Women’s rights were acknowledged, but only briefly and without concrete commitments. The rhetoric avoided deep engagement with economic inequality, minority rights, or how to dismantle existing structures of repression.

Instead, the narrative centred on emotional unity, historical pride, and trust in Pahlavi’s leadership as the key to a better future. This heavy reliance on symbols and broad slogans allowed the conference to project an image of strength and cohesion, but left unanswered the practical questions about how such a vision would be achieved in reality.

Broader Implications and Risks

The Munich conference was more than a stage for opposition speeches — it was also a display of the political culture shaping the Iranian right-wing in exile. Reza Pahlavi’s movement, although wrapped in the language of democracy and unity, has shown clear tendencies toward authoritarianism. In recent years, his supporters — often led in tone and messaging by his wife (Yasmine Pahlavi) — have engaged in widespread campaigns of online harassment, character assassination, and smear attacks against critics. These have not been limited to political opponents from the left or republicans; even dissenting monarchists and former allies have been targeted. Such behaviour mirrors the tactics of authoritarian regimes, where silencing dissent becomes as important as challenging the main enemy.

This aggressive culture cannot be separated from the history of the Pahlavi monarchy itself. Under his father, Mohammad Reza Shah, Iran experienced rapid modernisation alongside severe political repression: censorship, the banning of opposition parties, and the notorious use of SAVAK, the secret police, to monitor, imprison, and torture dissidents. While Pahlavi claims to represent a democratic alternative, his reliance on controlled messaging, elite alliances, and personality cult imagery evokes the very system his family once led.

One of the most troubling aspects is his increasingly open acknowledgment of ties to certain figures within the IRGC — the same organisation responsible for decades of violent repression inside Iran. Pahlavi now speaks about these contacts publicly, framing them as potential allies in a post-Islamic Republic transition. Such alliances not only undermine his democratic credentials but also raise fears of a power structure shaped by elements of the very security apparatus that has brutalised Iranians for decades.

Pahlavi’s political positioning is also closely aligned with the interests of Israel, whose officials and political circles have openly endorsed him. His careful avoidance of directly naming Israel in sensitive contexts does little to hide this relationship, which is reinforced by his public support for its regional policies. For many Iranians, this alignment represents not only a foreign dependency but also an acceptance of geopolitical strategies that have little to do with the democratic aspirations of the Iranian people.

Taken together, these elements — a culture of silencing critics, a history of repression in his political lineage, ties to the IRGC, and alignment with Israel’s agenda — paint a picture of a movement that risks replacing one authoritarian order with another. Beneath the rhetoric of freedom, the political model on offer is one rooted in elite dominance, foreign patronage, and the suppression of dissent. In this sense, the Munich conference was not just a political rally, but a warning of the kind of future that could emerge if such forces succeed.

Sivash John,

Us among the 5-10 mills out of Iran, we could only play a tranionary Or peripheral role and more as a technocrat and not political appointee. And I believe that applies to reza Pahlavi too. no one should presume simply because she he it played a role that would give him incumbency and peaCOCK 🦚 throne for life and his heirs.

The permanent future of Iran is by and large vested w ten of 90 millions inside iran e no prior role beyond a major in the army or dept head in ministries if only they are clear from

Any alleged crime in the past 46 year

A timely warning. Projecting the Pahlavis as any kind of alternative to the Islamic Republic is only likely to reinforce the credibility of the latter. It is therefore important to debunk events like the Munich conference as unrepresentative of the democratic opposition to the Islamic Republic either in Iran itself or in the diaspora.