Last week, two cases of femicide have shaken Iran. First, a lawyer murdered his journalist wife, Mansoureh Ghadiri Javi with brutal blows from a knife and dumbbell. In another case, another male lawyer killed his wife and son before ending his own life.

According to the Iranian newspaper “Etemad“, at least 165 femicide cases were reported in Iran. These cases occurred from June 2021 to June 2023. This means, on average, one woman is killed every four days.

Domestic violence in Iran affects women across different social classes and backgrounds. Cultural, social, and economic structures make it difficult for women to seek help or escape these violent situations. Fear of social consequences, lack of support, and ignorance of rights trap many women in danger. The killings are often justified by “honor,” jealousy, or family disputes. They turn deadly because of societal and legal structures that reduce punishment for these acts.

These recent cases highlight a disturbing trend. The men involved should have been defenders of the law. Instead, they were the perpetrators of these heinous acts. Both cases show men who, after committing murder, also attempted to end their own lives. These are not just isolated events; they reflect deep flaws within society and the legal system.

Historical Context of Femicide in Iran

The history of femicide in Iran stretches across decades, deeply rooted in the cultural, social, and legal fabric of the society. The term “femicide” refers not just to the act of killing women, but also to the broader systems that enable and excuse it. In Iran, femicide is often tied to “honor” or “chastity,” with many killings justified as acts of restoring family honor or protecting societal values. These beliefs are backed by a patriarchal culture and laws that reinforce the subjugation of women.

In the early years of the modern state, social attitudes and laws positioned women as dependents within families, first as daughters, later as wives. This dependence was not only a reflection of cultural norms but was embedded within Iran’s legal framework. Laws placed women’s lives and bodies under the control of their male relatives, primarily fathers, brothers, and husbands. A daughter who was perceived as dishonoring her family could be “corrected” with violence, including death, and in many cases, these actions were either justified or overlooked by both law and society.

Over the years, few magazines and publications dedicated to women’s issues have highlighted these cases. They have documented countless instances of femicide. Reports from the 1980s onward reveal a chilling consistency. Women have continued to suffer violence at the hands of their families. Often, they face little legal recourse. Iran’s legal codes include provisions that either allow or reduce punishment for men who kill female relatives under the pretext of defending family honor. This legal leniency further embeds femicide into Iran’s social structure, turning it from individual crime to a sanctioned practice in the eyes of many.

The cultural idea of “honor” also plays a central role in femicide. The perception that a woman’s actions—whether in how she dresses, behaves, or even who she associates with—reflect the “honor” of her male relatives has historically given men a social and moral authority over women’s lives. A woman’s “dishonorable” actions are seen not as her own but as a reflection on her entire family. This concept persists despite the changing roles of women in Iranian society. Women have made strides in education, workforce participation, and social engagement, yet these advances have not erased the deeply ingrained notion that a woman’s behavior must be controlled to preserve family honor.

In recent years, while some legal amendments have been made, the core structure of the legal and cultural systems that allow femicide remain largely unchanged. Iran’s laws still grant major leniency to men who commit these crimes, particularly when “honor” or “family reputation” is cited as a reason. For many women, the threat of violence continues to hang over them, as social and legal protections stay inadequate. In some cases, these laws seem almost to encourage femicide, sending a message that male relatives have a right to decide the fates of the women under their “protection.”

Narratives of Victims and Survivors

The impact of femicide in Iran becomes painfully clear through the stories of individual women—victims whose names become symbols of injustice and sorrow. These stories are not just personal tragedies; they illustrate the crushing weight of cultural and familial expectations on women’s lives. Women like Tahereh, Romina, and countless others have become known because their deaths, though heartbreaking, reveal the brutal lengths to which families will go to uphold “honor.”

Tahereh was just sixteen years old when she became a casualty of her family’s sense of dishonor. Her story, published twenty years ago in a women’s magazine, shocked readers for its cold cruelty. Her father, believing claims that she was not a virgin on her wedding night, decided that her life was less valuable than the family’s reputation. Even after a medical examination proved her innocence, her fate was sealed by the accusation alone. Tahereh was murdered by her own father and uncle, who saw her as a stain on the family honor. Her story, though written decades ago, still resonates today. Tahereh’s death is not an isolated incident; it is emblematic of a pattern in which suspicion alone is enough to justify taking a woman’s life.

Romina’s story is similarly chilling and more recent, showing that little has changed in the legal and cultural landscape. At fourteen years old, Romina attempted to escape with a man she loved. Her father found her, and despite Romina’s pleas for protection, the authorities sent her back home, trusting that her father would not harm her. Days later, he took her life in a horrific act of “honor” killing, using a sickle to decapitate her in their own home. Romina’s death created a wave of shock and horror in Iran, particularly because she had sought help, fearing exactly what would happen if she returned to her father. The system failed her, returning her to an environment where her life was in jeopardy.

These stories shed light on the brutal dynamics of power and control within Iranian families and the immense social pressure to conform to traditional values. In both cases, the law was powerless to prevent the violence or provide justice after the fact. Many femicides are never reported in detail, hidden behind closed doors or brushed off as private, family matters. The silence surrounding these cases stems not only from the fear of retribution but from the deeply ingrained belief that family honor supersedes an individual’s right to live freely.

Some women who survive violent attacks face long-term physical and psychological scars, yet their voices are often ignored. Many survivors cannot openly speak about their experiences without risking their safety or further shame for their families. In rare cases where survivors come forward, they reveal a society reluctant to sympathize with women who have “dishonored” their families. Despite the trauma they endure, survivors often find themselves ostracized, labeled as “tainted” or “dishonorable” for actions that may be as simple as choosing their own partner or rejecting restrictive customs.

Through these narratives, it is clear that femicide in Iran is not merely a series of isolated incidents; it is a reflection of a pervasive culture that views women as vessels of family honor, to be protected or punished as men see fit. For every Tahereh or Romina, there are countless others whose names and stories remain unknown, their voices silenced in the name of tradition. Their narratives, whether as victims or survivors, underscore the urgent need for legal reform and a cultural shift toward recognizing the inherent rights of women to live without fear.

Role of Family and Community in Femicide

In Iran, family and community play crucial roles in perpetuating the cycle of femicide. Femicide is rarely seen as an individual act of violence; it is often a collective expression of social expectations, family values, and community pressure. When women defy or appear to defy accepted norms, particularly around issues of sexuality and autonomy, they are not just seen as personal disappointments to their families. Instead, they are perceived as threats to the family’s social standing and reputation within the community.

The family unit in Iran has traditionally been seen as a sacred structure, with strict roles assigned to each member. Women and girls are often viewed as bearers of the family’s “honor,” with the men positioned as guardians of this honor. The notion of honor is deeply intertwined with a woman’s behavior, appearance, and relationships, making her subject to scrutiny from not only her immediate family but also extended relatives and neighbors. Men, particularly fathers, brothers, and husbands, feel a responsibility to monitor the conduct of their female family members and are expected to take action if they perceive any threat to family reputation. In these settings, the community often reinforces these expectations, directly or indirectly pressuring families to control “rebellious” or “disobedient” women.

Community pressure can amplify the intensity of these expectations. Families may feel compelled to take extreme actions, such as femicide, to avoid public shame. In many cases, friends, neighbors, and even distant relatives may suggest or encourage punitive measures against women deemed to have dishonored the family. This collective mindset sees “honor” as something that must be preserved at any cost, and any threat to it, real or imagined, is met with swift retribution. For instance, in Romina’s case, her father reportedly faced relentless criticism from neighbors and relatives who condemned him for allowing his daughter to associate with a man of her choice. When he ultimately killed her, many of those same community members saw it as a necessary act of discipline rather than a crime.

The role of the community does not end with the act of violence itself. After a femicide occurs, community members may rally around the perpetrator, viewing him as someone who has bravely defended the family’s honor. Neighbors and relatives may even support or justify his actions publicly, reinforcing the notion that such violence is an acceptable response to a woman’s perceived transgression. In cases where the killer faces legal consequences, some members of the community might advocate for leniency, further minimizing the gravity of the crime. This type of collective endorsement normalizes violence against women and discourages other families from challenging or rejecting the idea of “honor” as justification for abuse.

The family and community together create an environment where women are vulnerable to violence if they step outside of socially accepted roles. The presence of these cultural norms makes it almost impossible for women to escape from their assigned roles without facing potential harm. Family and community expectations create a constant surveillance system around women, with every aspect of their lives—education, work, friendships, marriage—dictated by the need to maintain family honor. This dynamic is not unique to rural or conservative areas; even in urban, progressive communities, the concepts of honor and shame play significant roles in shaping women’s lives, albeit in less visible ways.

In this complex web of family and community expectations, women’s lives and choices are severely restricted. Any act of defiance or perceived disobedience is considered a stain on family honor that must be “cleansed.” The overwhelming pressure to conform and the consequences of non-compliance reveal the frightening extent to which family and community can dictate the lives and deaths of women in Iran. For many women, the possibility of freedom is overshadowed by the constant, looming threat of violence—a reminder that their lives are not entirely their own.

Legal Implications and Loopholes

Iranian law plays a critical role in sustaining the conditions that allow femicide to persist. While laws are theoretically meant to protect citizens, certain loopholes and legal codes actually permit, or at the very least, lessen the punishment for men who commit femicide. These legal gaps create an environment in which perpetrators of femicide can act with relative impunity, knowing that the law is more likely to protect them than to hold them accountable.

One of the most problematic legal aspects is the concept of “honor defense” embedded in Iranian law. Under Iran’s Penal Code, Article 630 permits a husband to kill his wife and her lover if he catches them in an act of adultery, provided he is “certain” that she was not coerced. The law assumes that a woman’s infidelity tarnishes a man’s honor to such a degree that it justifies taking her life. This legal clause reinforces the idea that a woman’s actions are a direct reflection of her husband’s reputation and that violence is an acceptable method to address issues of perceived dishonor.

Additionally, Article 220 of the Islamic Penal Code grants fathers and grandfathers a significant level of authority over their children, including their daughters. Under this law, a father or paternal grandfather who kills his child is exempt from capital punishment and may only face light sentences, often as short as a few years. This legal exception, known as “ghesas” (retribution), implies that fathers have ownership rights over their children and, to an extent, can decide their fate. This leniency in the case of so-called “honor killings” sends a chilling message to society: that men, especially fathers, have the ultimate control over female family members, and the law will not intervene harshly, even in cases of murder.

These loopholes illustrate how Iranian law fails to protect women and, in some cases, actively enables the continuation of gender-based violence. The law allows men to act as enforcers of “honor,” essentially granting them power over women’s lives and bodies. Many activists argue that these laws are relics of a patriarchal system that views women as property rather than as individuals with rights. The absence of severe penalties for femicide, particularly in cases where honor is cited, encourages men to take matters into their own hands, knowing they will face minimal consequences.

This legal leniency is exacerbated by the fact that judges in Iran often have significant discretion in interpreting the law. Many judges interpret cases involving honor killings within a cultural framework that views women’s chastity as paramount. In some cases, judges may reduce sentences for men who claim they were defending their family’s honor, regardless of whether the victim was proven innocent or guilty of the alleged transgression. This judicial discretion often results in reduced prison terms, parole, or even acquittal in cases of femicide.

Moreover, the social acceptance of honor as a valid reason for violence further weakens the likelihood of reform. Efforts to amend the Penal Code to remove or modify these provisions have faced strong resistance, as these laws are seen by some as a reflection of cultural values. Even when proposals for stricter penalties gain traction, conservative lawmakers and community leaders often argue that such changes would undermine family values and social order. Consequently, these legal provisions remain largely unchallenged, leaving women vulnerable to violence and at the mercy of family and community expectations.

The legal system in Iran, rather than providing justice for victims, tends to reinforce patriarchal control. For many women, the law is not a source of protection but a tool that upholds the power of those who seek to control them. Until significant legal reforms are implemented, and the concept of honor is no longer embedded within the justice system, women will continue to live under the threat of violence. These laws, with their loopholes and cultural justifications, demonstrate how deeply ingrained gender-based violence is in both the legal and social framework of Iran.

Cultural Justifications and Social Attitudes

Cultural beliefs and social attitudes toward “honor” and “chastity” play an immense role in perpetuating femicide in Iran. In many communities, a woman’s value is closely tied to her perceived purity and obedience, and any deviation from these expectations is seen as a direct threat to the honor of her family. These beliefs are deeply embedded in the social fabric, passed down through generations and reinforced by both cultural norms and religious interpretations. As a result, many people accept violence against women as a legitimate response to perceived dishonor.

The concept of “honor” in Iranian society is not merely a personal value; it is a public one that concerns the entire family and, in many cases, the community. Women are often regarded as the physical embodiment of this honor, and their actions are scrutinized as reflections of their family’s moral standing. Behaviors considered “dishonorable” can include a wide range of actions, from choosing one’s own friends or partners to dressing in a way deemed inappropriate or appearing in public spaces alone. Women are expected to conform to traditional roles that limit their freedom, and any attempt to assert independence can be met with hostility or violence.

Social attitudes toward honor are heavily influenced by a mix of cultural traditions and religious interpretations. These beliefs vary in intensity across regions and communities, but the underlying message is the same: a woman’s role is to uphold the family’s reputation, and failure to do so invites severe consequences. For instance, in some conservative communities, even the mere rumor of inappropriate behavior is enough to justify punishment, regardless of whether the woman in question has actually done anything wrong. This belief creates an environment where women’s lives are closely monitored, and any perceived transgression can be met with immediate and sometimes lethal repercussions.

Religious interpretations also play a role in how honor is defined and enforced. In some cases, certain interpretations of religious texts are used to justify control over women’s behavior, as well as the use of violence to “correct” or “punish” perceived moral failings. While there is debate among religious scholars regarding these interpretations, in practice, many communities adhere to conservative views that reinforce patriarchal control over women. This adds a layer of religious validation to cultural beliefs, making it even more challenging to change these attitudes or promote women’s rights.

In many cases, women themselves may internalize these beliefs, accepting their role as carriers of family honor and supporting the very norms that restrict their freedoms. This phenomenon, known as “internalized misogyny,” means that some women also become enforcers of these standards, either by pressuring younger women to conform or by staying silent in the face of violence. This internalization reflects the deep-rooted nature of these cultural beliefs, showing that the control over women’s lives extends beyond the actions of men to a collective mindset embraced by the community.

Efforts to change these cultural attitudes have faced substantial resistance, as they are seen by some as attempts to undermine traditional values. Feminist activists, social reformers, and human rights organizations working in Iran have tried to promote awareness of women’s rights and advocate against gender-based violence. However, these efforts are often met with backlash from conservative voices who argue that such changes threaten the moral and social fabric of society. As a result, change has been slow, with many people still holding onto the belief that a woman’s behavior should be policed in order to protect family honor.

The strong attachment to honor and chastity within the culture serves as a powerful justification for femicide. In many cases, perpetrators of femicide do not see their actions as criminal but as necessary corrections to moral failings. For them, the act of killing a woman who has “dishonored” her family is seen as a restoration of balance, a way to reclaim the family’s social standing. This mindset not only dehumanizes women but also legitimizes violence as a solution to social or personal grievances.

These cultural justifications and social attitudes reveal how deeply femicide is woven into the fabric of Iranian society. Until there is a shift in these attitudes, women will continue to face immense pressure to conform to restrictive roles and will remain vulnerable to violence if they step outside of these expectations. Changing these beliefs is not simply a matter of altering individual mindsets; it requires a transformation of the values and norms that define gender roles, honor, and the very definition of respectability in society.

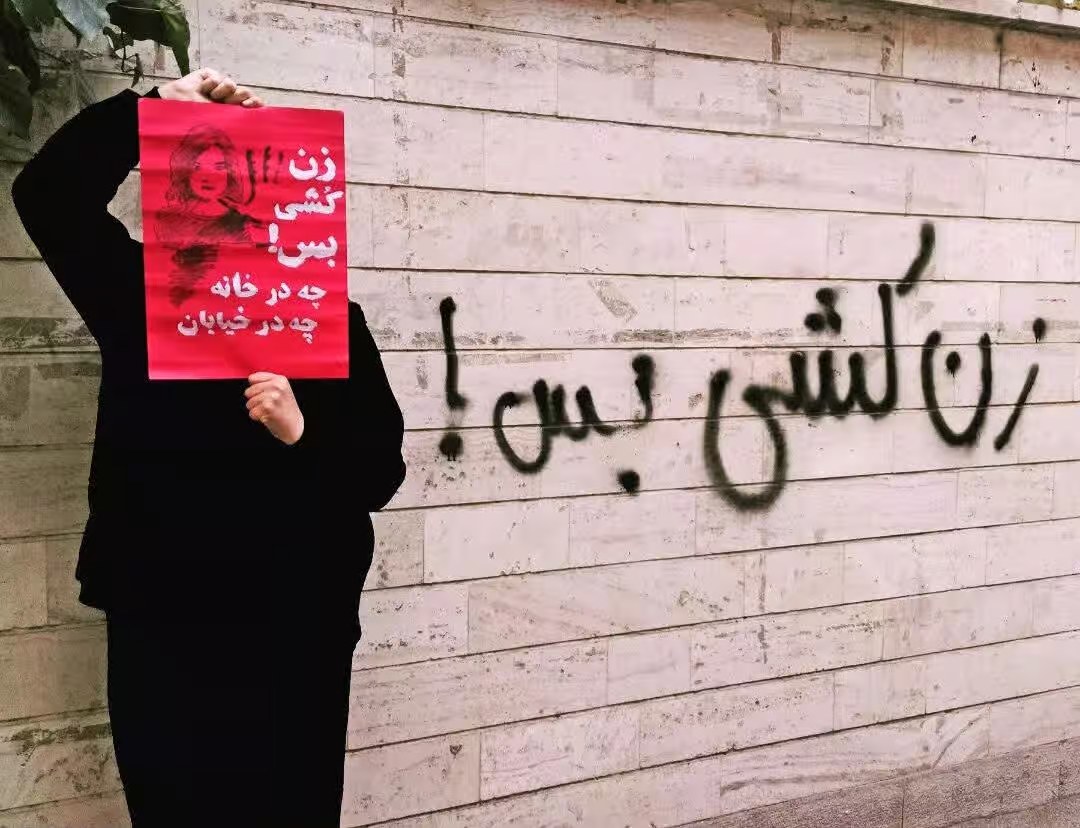

Resistance and Advocacy

Despite the challenges, there are activists, feminists, and human rights advocates in Iran who are tirelessly working to address and combat femicide. These individuals and organizations strive to raise awareness, push for legal reform, and offer support to women who are at risk. Their work represents a growing movement within Iran that seeks to challenge the cultural, legal, and social structures that enable violence against women. However, this resistance is fraught with obstacles, as advocates often face backlash, legal restrictions, and social stigma for challenging entrenched norms.

One significant area of focus for advocates is raising awareness about femicide and gender-based violence. Through publications, workshops, and online campaigns, activists aim to educate the public on the issues surrounding femicide, emphasizing that it is not a matter of family honor but a grave violation of human rights. Publications like Zanan (Women) magazine and its successor Zanan-e Emruz (Women Today) have been critical in documenting cases of femicide and shedding light on the realities faced by Iranian women. By sharing stories of victims like Tahereh and Romina, these publications not only honor the memories of those who lost their lives but also create a public dialogue around the need for change.

Legal reform is another critical focus. Activists argue that Iran’s penal code must be revised to remove leniencies for honor-based violence and to implement strict penalties for all acts of femicide. Proposals have been put forward to amend articles of the penal code, particularly those that provide lighter sentences for fathers and husbands who commit acts of femicide. However, efforts to reform these laws often encounter resistance from conservative lawmakers and religious authorities who argue that such changes would erode traditional values and undermine the authority of the family. As a result, progress on legal reform has been slow, leaving advocates frustrated but undeterred in their pursuit of justice.

Human rights organizations, both domestic and international, have been instrumental in documenting and reporting cases of femicide in Iran. Organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have raised global awareness about femicide in Iran, putting pressure on Iranian authorities to address gender-based violence. However, activists in Iran often face limitations on their freedom of expression and assembly, making it challenging to organize large-scale movements. In some cases, advocates who speak out against femicide are detained or silenced by authorities, particularly if they are seen as opposing state policies or traditional values.

Community-based support networks have also emerged as part of the resistance against femicide. These networks provide safe spaces for women who are at risk, offering counseling, legal advice, and shelter. In regions where governmental support is limited or nonexistent, these community organizations serve as lifelines for women seeking to escape abusive situations. Although their resources are limited, these groups have managed to create small but significant changes in the lives of individual women, providing them with a chance to reclaim their independence and safety.

Social media has become a powerful tool for activists and feminists in Iran to voice their opposition to femicide. Platforms like Twitter, Instagram, and Telegram allow advocates to share information, organize campaigns, and create virtual communities of support. Hashtags, viral posts, and online petitions have amplified the voices of women’s rights activists, reaching audiences both within and outside Iran. While authorities often monitor and restrict internet access, social media remains an essential tool for raising awareness and mobilizing support, allowing activists to bypass traditional media restrictions and connect directly with the public.

The fight against femicide in Iran is not without risk. Many activists and advocates face personal threats, social ostracism, and even legal consequences for their work. However, the growing awareness and advocacy around femicide represent a hopeful sign that change is possible. These efforts, though small in scale, challenge the status quo and offer a vision of a future where women are free from the threat of violence. Each campaign, protest, and publication adds to the momentum of a movement that seeks to redefine honor, protect women’s rights, and create a society where every individual can live without fear.

Comparative Analysis with Other Societies

Examining femicide in Iran alongside cases from other countries reveals both universal and unique factors influencing gender-based violence. While the specific cultural, religious, and legal frameworks may differ, the underlying patterns of control, patriarchal values, and societal expectations concerning women are common threads that often shape femicide worldwide. By comparing Iran’s situation with that of other countries, we can better understand the scope of the problem and recognize the potential paths for change.

In many parts of the world, femicide is linked to “honor,” with similar justifications seen in countries across the Middle East, South Asia, and Latin America. For instance, in countries like Pakistan, Jordan, and Afghanistan, women who are perceived to bring dishonor to their families may face violence, often with limited legal repercussions for the perpetrators. In these societies, as in Iran, cultural beliefs reinforce the idea that a woman’s actions reflect her family’s moral standing, and thus any deviation from expected behavior can provoke fatal consequences. Here, patriarchal control and a sense of collective honor encourage violence, just as in Iran, and attempts to reform these practices often face opposition from traditional or conservative sectors.

Latin American countries, particularly Mexico, have also seen a troubling rise in femicides, with the term itself originating from activists in the region. In many cases, femicides in Latin America occur in contexts of domestic violence or organized crime, and like Iran, women in these regions often suffer from systemic negligence. The prevalence of “machismo,” a cultural belief that men have authority over women, drives much of the violence in Latin America, similar to the influence of patriarchal authority in Iran. Legal frameworks in Latin American countries have, however, begun to evolve, with Mexico and Argentina instituting special laws and creating units within law enforcement specifically tasked with addressing femicide. Though challenges remain, these legal measures represent significant steps toward holding perpetrators accountable and may serve as potential models for Iran and other countries.

In Western countries, while honor killings are less common, femicide is frequently connected to domestic violence, stalking, and misogyny. Countries in Europe and North America have implemented laws specifically addressing domestic violence and have made strides in criminalizing femicide as a distinct offense. For example, Italy and France have both recognized femicide as a pressing social issue and implemented more severe penalties and monitoring for offenders. In countries like Canada and Australia, grassroots campaigns have pressured governments to improve the protective measures for women, leading to increased resources for shelters and legal services. These Western nations also provide educational programs aimed at shifting social attitudes regarding gender equality, recognizing that changes in law must be accompanied by changes in cultural perceptions of women.

The contrast between these countries and Iran highlights the impact of both legal reforms and social activism. In countries where laws have evolved to protect women, awareness campaigns and community education often go hand in hand with legislation. Although social attitudes do not change overnight, sustained advocacy has demonstrated that it is possible to transform public opinion on women’s rights and shift norms surrounding violence against women. This cultural shift has proven crucial for reducing femicide rates in places where advocacy and reforms have taken root.

However, it is essential to recognize the unique challenges that Iranian activists face in their fight against femicide. Unlike many countries that benefit from a relatively free press and fewer restrictions on activism, Iran imposes limitations on both freedom of expression and freedom of assembly, making it difficult for advocates to mobilize support or call for legal changes. International human rights organizations have noted that the lack of legal reform in Iran is partially due to these restrictions, as the government often views calls for gender equality as challenges to cultural or religious values. Therefore, while the experiences of other societies offer valuable lessons, they also underscore the specific obstacles Iran faces in addressing femicide within its borders.

The comparisons between Iran and other countries illustrate both the universality of femicide as an issue and the diverse approaches to combating it. While each society has its own cultural and legal framework, the underlying problem of patriarchal control is a common factor that must be addressed. For Iran, meaningful change will likely require not only legal reform but also a shift in social attitudes—a task that other countries’ experiences suggest is challenging but ultimately achievable with persistent effort and support.

The Role of Media and Public Perception

The media in Iran plays a significant role in shaping public perception of femicide and gender-based violence. How femicide cases are portrayed—or ignored—by the media affects not only public opinion but also the likelihood of legal and cultural change. For decades, many instances of femicide have either been downplayed or depicted as private, family matters, thus minimizing their impact and obscuring the need for urgent reform. However, some progressive media outlets and independent journalists have sought to bring attention to these cases, highlighting the systemic issues that contribute to femicide and pushing for a societal response.

In official state media, coverage of femicide cases is often limited and selective, especially when the cases reflect poorly on traditional cultural norms or question the existing legal framework. The state-controlled media is unlikely to criticize patriarchal values openly or to promote reforms that could be seen as a challenge to conservative values. Consequently, many cases of femicide are either underreported or presented in ways that reinforce stereotypes about “dishonorable” behavior by victims, subtly suggesting that the violence was justified by the woman’s actions. This approach shapes public perception, making it easier for society to ignore the depth of the femicide crisis or to accept it as an unfortunate but unavoidable part of life.

However, independent and international media have played an increasingly important role in documenting femicide cases and exposing the realities of gender-based violence in Iran. These platforms have provided detailed reports on individual cases, explored the social and legal factors involved, and given a voice to survivors and families affected by femicide. Through these efforts, independent media has managed to spark public conversations about the status of women in Iran, especially among younger generations who are more likely to support gender equality.

Social media has also emerged as a critical tool for raising awareness about femicide, offering a space where activists and ordinary citizens alike can share information, voice their opinions, and organize campaigns. Platforms such as Instagram, Twitter, and Telegram have allowed Iranian women’s rights advocates to bypass the restrictions of state-controlled media, using hashtags, viral posts, and online petitions to draw attention to femicide cases. In high-profile cases, such as the murder of Romina Ashrafi, social media outrage has pressured authorities to respond, even if only temporarily. While online activism does not replace systemic reform, it plays a significant role in shaping public perception, challenging traditional narratives, and fostering solidarity within the community.

The power of media and public perception in addressing femicide lies not only in raising awareness but also in challenging societal norms. When media coverage shifts from treating femicide as isolated incidents to framing it as a systemic issue, it forces the public to confront the structural inequalities that fuel gender-based violence. This change in narrative is crucial for creating a climate where legal reforms are possible, as a well-informed public is more likely to support policies that protect women’s rights.

Nevertheless, the impact of media coverage on public perception has its limits, particularly given Iran’s strict censorship laws. Independent journalists and activists often face harassment, detention, or surveillance for reporting on femicide or advocating for women’s rights. This environment makes it difficult for media outlets to cover femicide cases comprehensively or to explore their broader implications. Despite these challenges, media coverage remains one of the most effective tools for creating awareness, even if progress is slow and met with resistance.

In sum, the role of media in shaping public perception of femicide in Iran cannot be overstated. While state media often downplays the issue, independent and social media have provided alternative narratives that expose the realities of gender-based violence. By highlighting the personal stories behind the statistics and advocating for change, media outlets and online activists are helping to foster a public understanding that could eventually drive meaningful reform. Public perception is a powerful force, and when it shifts, it has the potential to challenge long-standing cultural norms and demand accountability from both society and the legal system.

Future Perspectives

The struggle against femicide and gender-based violence in Iran is profoundly tied to the systematic violation of women’s rights, deeply rooted in Islamic laws that restrict women’s freedoms and autonomy. These laws reinforce gender inequality and uphold a legal framework that views women as subordinate to men, with limited rights in marriage, divorce, child custody, and inheritance. For many women in Iran, the legal system does not serve as a source of protection but rather as a mechanism of control and oppression.

Iran’s legal restrictions extend beyond individual rights to also severely limit the ability of women activists to organize and advocate for change. Forming an association, organization, or party specifically dedicated to women’s rights is nearly impossible in Iran due to strict state control and the fear of repression. Independent women’s rights organizations are often treated as threats to national security, and activists face surveillance, detention, and even imprisonment for attempting to address gender-based violence or other social injustices. This environment of repression prevents women from advocating for their rights and stifles collective movements that could otherwise bring about social and legislative change.

Given these extensive restrictions and the hostile environment for women’s rights activists within Iran, the need for international feminist support is urgent. The Iranian feminist movement and individual women’s rights activists could benefit immensely from solidarity and advocacy from the global feminist community. International organizations can help by raising awareness about the realities of women’s oppression in Iran, amplifying the voices of Iranian activists, and providing platforms where they can speak freely. This global support can bring international pressure on Iranian authorities, urging them to respect human rights and end the persecution of women’s rights advocates.

International feminist networks can also provide resources, training, and funding to help sustain Iran’s feminist movement. These resources could include safe channels for communication, digital security training to protect activists’ privacy, and legal support for those facing prosecution. Through partnerships, international organizations can strengthen the resilience of Iranian activists and empower them to continue their work despite government repression. In a context where local efforts are consistently hindered, international support offers critical lifelines and shows activists that they are not isolated in their fight for justice.

Furthermore, international feminist support can play a role in pressuring global leaders to address Iran’s violations of women’s rights in diplomatic contexts. Calls for human rights conditions in trade agreements, resolutions in international bodies, and public statements by foreign governments can all signal to the Iranian regime that its treatment of women and activists is unacceptable on the world stage. This form of pressure, when combined with the voices of Iranian feminists, can amplify demands for change and hold Iran accountable for its systematic violations of women’s rights.

The international feminist community’s support is not just a matter of solidarity; it is a necessary action to help Iranian women challenge the oppressive structures that govern their lives. By recognizing the courage of Iranian women and amplifying their demands, the global feminist movement can help dismantle the isolation imposed by censorship, support activists facing severe risks, and promote a future where women in Iran can pursue justice, equality, and freedom. The resilience of the Iranian feminist movement, despite overwhelming obstacles, stands as a testament to the unyielding spirit of these activists. With international backing, there is hope for a future in which women’s rights in Iran are no longer systematically violated but protected, respected, and celebrated.