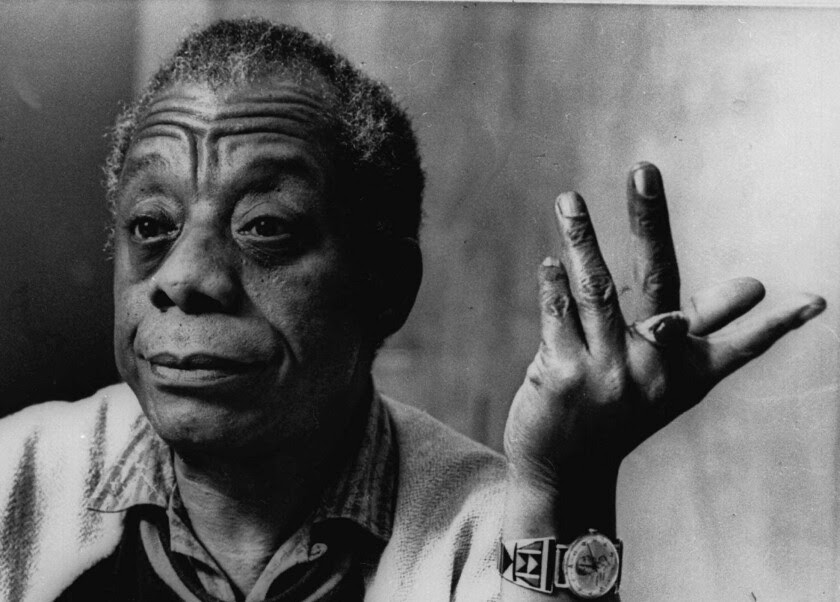

Of Latitudes Unknown stands as a comprehensive examination of James Baldwin’s profound intellectual vision. This scholarly work presents a selective yet rigorous reevaluation of existing Baldwin studies, while introducing novel critical perspectives, themes, and methodologies. The volume extends the current discourse by deconstructing previous fragmentations in Baldwin’s corpus and drawing new connections between his essays and novels, his polemical writings and aesthetic considerations, as well as his engagement with visual media and his multicultural identities.

Unlike prior studies, this book places significant focus on lesser-explored aspects of Baldwin’s inventive mind: his bilingual articulations, his later interactions with Africa, his engagements with French media, and his underappreciated works in literary journalism. The text also explores Baldwin’s connections with the Arab world, his prescient contributions to what would become contemporary film and media studies, and his complex role as a public intellectual.

Intellectual Resistance and Identity

in the Works of Edward Said and James Baldwin

In his groundbreaking 1994 book, Representations of the Intellectual, Edward Said artfully establishes a compelling connection between the political paths of African Americans and his own resolute advocacy for Palestinian self-determination. Said reflects, “there can be little doubt that influential figures such as Baldwin and Malcolm X have significantly shaped my own understanding of the intellectual’s role. It is the ethos of resistance, rather than conformity, that resonates with me because… the essence of intellectual endeavor lies in challenging the prevailing system at times when advocacy for marginalized and disadvantaged communities is overwhelmingly impeded.” Said further explains how his involvement in Palestinian issues has profoundly deepened these convictions, offering a deeply personal insight into his ideological development.

In his 1972 work, No Name in the Street, James Baldwin offers a poignant reflection of his time in Paris, serving partially as a memoir. He draws an evocative comparison between his self-imposed exile and the experiences of North African migrants in the city. Baldwin notes, “The Arabs were together in Paris, but the American blacks were alone… I will not say that I envied them, for I didn’t, and the directness of their hunger, or hungers, intimidated me; but I respected them, and as I began to discern what their history had made of them, I began to suspect, somewhat painfully, what my history had made of me”. His introspective analysis beautifully captures the intricate dynamics of identity, displacement, and community among diasporic groups.

From 1966 to 1979, Baldwin’s writings on Palestine solidify an emerging understanding of the region’s colonial history as a critical aspect of Western imperialism. His perspective, described by Said as “Zionism from the standpoint of its victims” (Said, “Zionism”), frames Zionism as a symbol of the broader historical project of European and Western colonial rule. Baldwin’s insights provide a valuable lens through which the Israel–Palestine conflict can be viewed, enriching our comprehension of its deep-rooted complexities.

Together, these works by Said and Baldwin not only delve into the struggles faced by marginalized communities but also explore the role of intellectuals in advocating for change and understanding across cultural and political divides.

Baldwin’s understanding of crossroads in Afro-Arab history is prefigured by the originary moment of his exile. In No Name in the Street, Baldwin famously recalls his “escape” from America as boundaried by two versions of the Occident: the first, Europe, to which he flees, the second, Israel, his road not taken. “Four hundred years in the West had certainly turned me into a Westerner—there was no way around that,” he writes. “But four hundred years in the West had also failed to bleach me—And if I had fled, to Israel, a state created for the purpose of protecting Western interests, I would have been in yet a tighter bind: on which side of Jerusalem would I have decided to live?”

We should note firstly Baldwin’s appreciation of his “strange birth” into exile in 1948 as concurrent with the imperial world’s laying down of a new colonial mark—partition—across Palestine. Here, Baldwin’s perspicacious reading of the creation of the state of Israel as colonial project likely reflects his political training of the 1940s. This was his self-avowed period as a “Trotskyite” with the Young People’s Socialist League, which stood independent of both the Communist Party and even the popular Black Left—like Du Bois—in uncritical support for the creation of Israel. Rather, Baldwin comprehends a future theme of his work in 1948, namely, that both Jews and Palestinian Arabs may be metonymic of his own displacement from America and that in living as an outsider within the West, he is his own signifier of apartheid.

Hence, shortly before his arrival in Paris, Baldwin began to view the newly formed South African state—established in the same year as Israel—as one element of an imaginary Maginot Line of postwar colonial influence that stretched from Palestine in Western Asia to Vietnam in Southeast Asia. From his Parisian vantage point, notably, the Algerian situation was evident. He observed that the French were “still hopelessly engaged in conflict in Indo-China.” Baldwin noted, “The Arabs were not involved in Indo-China, yet they were part of an empire that was rapidly and visibly disintegrating, and entangled in a history reaching its climax in the most literal and alarming way”.

Baldwin carried memories of seeing Algerians and other non–northern Europeans, including Jews, “corralled into prisons” in Paris when he ventured to Israel in 1961. Interesting for our purposes, he also carried in his luggage the unfinished manuscripts for both Another Country and extensive notes for “Down at the Cross,” the essay published in The New Yorker in 1962 as “Letter from a Region in My Mind” and then in 1963 as The Fire Next Time.

He arrived in Tel Aviv as a guest of the Israeli government, touring the Negev desert, Haifa, and a kibbutz near the Gaza Strip. As Keith Feldman notes, Baldwin’s primary response to his visit was a deepened and self-reflective ambivalence elicited by partition. Baldwin is tormented by the apartheid geography of the region—hostile Muslim citizens surrounding an Israeli state “forced to control the movement of Arabs.”

Thus though Israel does function as a “homeland, however beleaguered,” Baldwin wrote, “you can’t walk five minutes without finding yourself at a border … and of course the entire Arab situation, outside the country, and above all, within … the fact that Israel is a homeland for so many Jews … causes me to feel my own homelessness more keenly than ever”. For Feldman, the 1961 Israel visit is precursive and predictive of Baldwin’s declaration to Margaret Mead some ten years later—“You have got to remember … that I have been, in America, the Arab at the hands of the Jews”—a quotation to which we shall return.

Yet what can be said definitively here is that Baldwin apprehended the Israel visit as a real and symbolic turning point in understanding the physical and ideological contours of what Alex Lubin has called the “Afro-Arab Political Imaginary.” As Baldwin wrote later, “When I was in Israel, it was as though I was in the middle of The Fire Next Time. I didn’t dare go from Israel to Africa, so I went to Turkey, just across the road”.

Baldwin’s assertion that being in Israel felt akin to experiencing the racial turmoil of America underscores his developing thoughts on race, the identity of Arabs, and Western modernity. He thoughtfully connects these ideas in his seminal work, “The Fire Next Time”, discussing the parallels between the displacements of Arab and African American communities. This connection is illustrated through two geographic and temporal references in his 1962 essay: initially, he brings up the Tunisians who, in 1956—a pivotal moment in both Western and African history—challenged the French rationale for maintaining colonies in North Africa by questioning whether the French themselves were prepared for self-governance.

Later in the essay, Baldwin agrees with Elijah Muhammad‘s assertion that no historically respected peoples lacked sovereignty over their land; he highlights that every nation has its defined territory and flag, even the Jews, but the “so-called American Negro” remains oppressed, insubstantially recognized, and destitute within a nation that has enslaved him for nearly four centuries and still fails to acknowledge him as a human being.

Much of James Baldwin’s explorations into issues of race and geopolitical shifts reflect a profound engagement with the Arab world. His discussions on the United States, particularly after 1967, highlight Arab, notably Palestinian, hardships as a reflection of Western imperial dominance. For instance, Baldwin’s essay from July 1966, “A Report from Occupied Territory,” draws parallels between the excessive policing and violence in black American communities and American military actions in Vietnam.

Baldwin starkly observes, “They are dying there like flies; they are dying in the streets of all our Harlems far more hideously than flies,” a comparison he also uses to depict the tragic fate of Algerians during the massacre in Paris. The notion of “occupation” utilized in this essay would resonate powerfully for those familiar with the Palestinian Liberation Organization’s characterization of Palestine as usurped native land, a theme Baldwin delves into earlier in “Letter from a Region in My Mind,” where he outlines the systematic dispossession of black and Muslim communities.

Clearly Baldwin saw in his X-ray examination of the Afro-Arab condition the skeleton not just of Western history but the master-slave dialectic played out on the backs of he who the former Black Panther Daniel calls, in The Welcome Table, “My Algerian brother.” Baldwin’s quest to represent the Arab then, as always, is a quest for freedom from the real and discursive political structures by which the West was won. Today, we might recognize fortress Europe, the Israeli apartheid wall—even the Arab Spring—as residual forms of those structures, and Baldwin and Said as brothers under the skin. We might also recognize in Baldwin a most radical impulse to explain our own present to ourselves, and to give us the tools, once again, to dismantle and rebuild the master’s burning house.

.