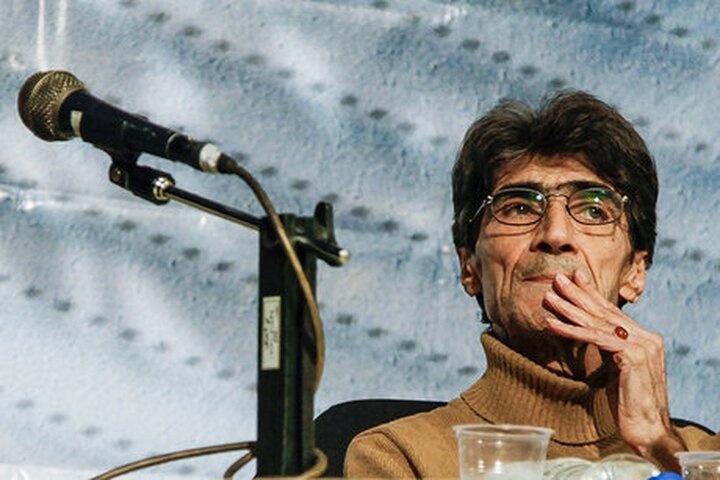

Nasser Taghvai, a renowned Iranian filmmaker and creator of enduring works, who for years resisted censorship and chose seclusion rather than making films under official policies, has passed away at 84. He was a pioneer of the Iranian New Wave and, at the same time, widely known to the public for his popular works. His legacy shaped my generation through “Captain Khorshid”—a creative adaptation of Hemingway—and the generation before mine through “My Uncle Napoleon.”

Your support helps keep this space alive but also ensures that these critical discussions remain accessible to all.

“My Uncle Napoleon” is a beloved pre-1979 TV series based on Iraj Pezeshkzad’s novel; it was banned after the Islamic Republic took power. The story’s hero/anti-hero is an old man called “Uncle” who blames “the enemy” for every incident at home, on the street, and in the city, spinning fantasies about himself and his past that are untrue or wildly exaggerated. The novel is set during the Allied occupation of Iran—an era when politics were dictated from elsewhere. This big joke about conspiracy thinking—really a tool officials use to dodge accountability by naming a foreign actor as the sole source of every crisis—became a common proverb in Iran and still resonates. Beyond the joke, it revealed a social mechanism: when there’s no institution for truth-checking and free collective action, paranoia becomes the shared language for explaining the world. That language shifts responsibility: if “the enemy did everything,” then no one is accountable.

“Captain Khorshid,” Taghvai’s creative adaptation of Hemingway’s “To Have and Have Not,” tells the story of a captain in southern Iran caught between repressive policies, the informal economy, and the ethics of action. In the film, smuggling is people’s response to a border that blocks any lawful way to live. The captain is constantly forced into gray-zone choices: rescue or transport; distrust or trust; break the law to save a life—or not. He isn’t a pure hero; he’s an agent who, each time, balances loyalty, livelihood, friendship, and risk, makes a situational decision, and pays the price. This is exactly the language we need at the social level too: an ethics born from practice, not slogans; solidarity fed by real experience, which thus recognizes complexity and diversity because it deals with different bodies, timelines, and needs.

If “My Uncle Napoleon” mirrors a mechanism of simplification—where weak free debate, the absence of collective judgment, and an eroded shared memory push society toward simple, all-knowing narratives and produce paranoia—then “Captain Khorshid” reminds us of the capacity to build middle paths: spaces where people, without turning themselves into heroes, create networks of care, share risk, and work to reduce suffering instead of ranking it. The “Uncle” mindset is dangerous for any solidarity movement: instead of listening and distinguishing differences, it hunts for ready-made binaries; it reduces people to types and turns society into a black-and-white canvas.

Now set these two lenses beside the space many of us inhabit in the West—especially in anti-racist and anti-colonial circles. The pain of Palestine shapes our conscience—and it should—but if that pain becomes the “master narrative,” it mutes other Middle Eastern realities: everyday structural corruption; censorship and self-censorship in media and art; bans on independent organizing and the erosion of social trust; gender-based violence at home and at work; sectarianism; and an informal economy that keeps millions afloat. All of these are local and multiple, and they don’t necessarily fit into the frame of “foreign intervention”—even though intervention does exist. Society isn’t one-note; choices differ; and any effort to reduce these differences to a single cause reproduces “Uncle Napoleon” in radical clothing.

From these two lessons we can draw a few grounded rules that honor diversity and keep us out of the paranoia trap: organize many voices (bring together workers’, women’s, queer, and ethnic/linguistic/religious minority narratives in every meeting and statement); connect experience to documentation and outcomes; legitimize internal disagreement (the right to dissent without automatic labeling); institutionalize two-way translation (carry knowledge and pain from the region’s languages into the host language and back—not just one-way); and replace “types” with “characters” (let people’s histories and agency show).

In a society that wouldn’t allow for this path, Nasser Taghvai chose to stop making films: “I’m trying, by not making films, to do my part in bringing this cinema down so that maybe something new can grow in its place. This wasn’t the cinema that the generations before us, our own generation, and the bright filmmakers after us wanted to create. Anyone who cares about this art and its future should try to make this collapse happen sooner, in the hope that a fresh sapling will grow instead.” — Nasser Taghvai (22 Tir 1320 – 22 Mehr 1404)

The final scene of “Dead Poets Society” offers a neat “mental cut” here: standing on a desk means stepping away from the everyday so we can see that same everyday more clearly. This gesture pushes back against the “Uncle” mindset that hands everything over to an invisible enemy; by changing the frame, differences and details suddenly appear—many voices, different choices, and small but real pathways to change. At the same time, this stance is close to the captain’s ethics: a collective act that doesn’t dodge the cost—the student knows expulsion or punishment is possible, and still stands.

So if we’re to move past paranoia and return to society, we need to unite these two lessons: “stand on the desk” to break the single narrative, and “move like the captain” to turn a fresh view into tangible action. The basic program is clear: organize many voices, legitimize disagreement, make outputs measurable, and invest in networks of trust instead of hero-making. From this angle, saying “O Captain! My Captain!” isn’t just saluting a teacher; it’s a commitment to seeing differently and building together—the path that takes us from a silencing, binary mind to a living society of action.