At the dawn of the 13th century in the Islamic calendar, Iranians were experiencing the end of World War I. Despite declaring neutrality, Iran was drawn into the conflict, becoming a battleground for the proxy war between the Russian, British, and Ottoman forces. This involvement was so significant that the withdrawal of Russian troops from Iran was included in the armistice treaty with Germany. However, the war, along with the weakness of the central government, led to the emergence of various protest movements across the country, from north to south and east to west. The situation was further worsened by famine and the spread of epidemics such as plague, cholera, and typhoid in different parts of Iran. The ship of hope that had risen from the Constitutional Revolution was now caught in the floods of endless hardships.

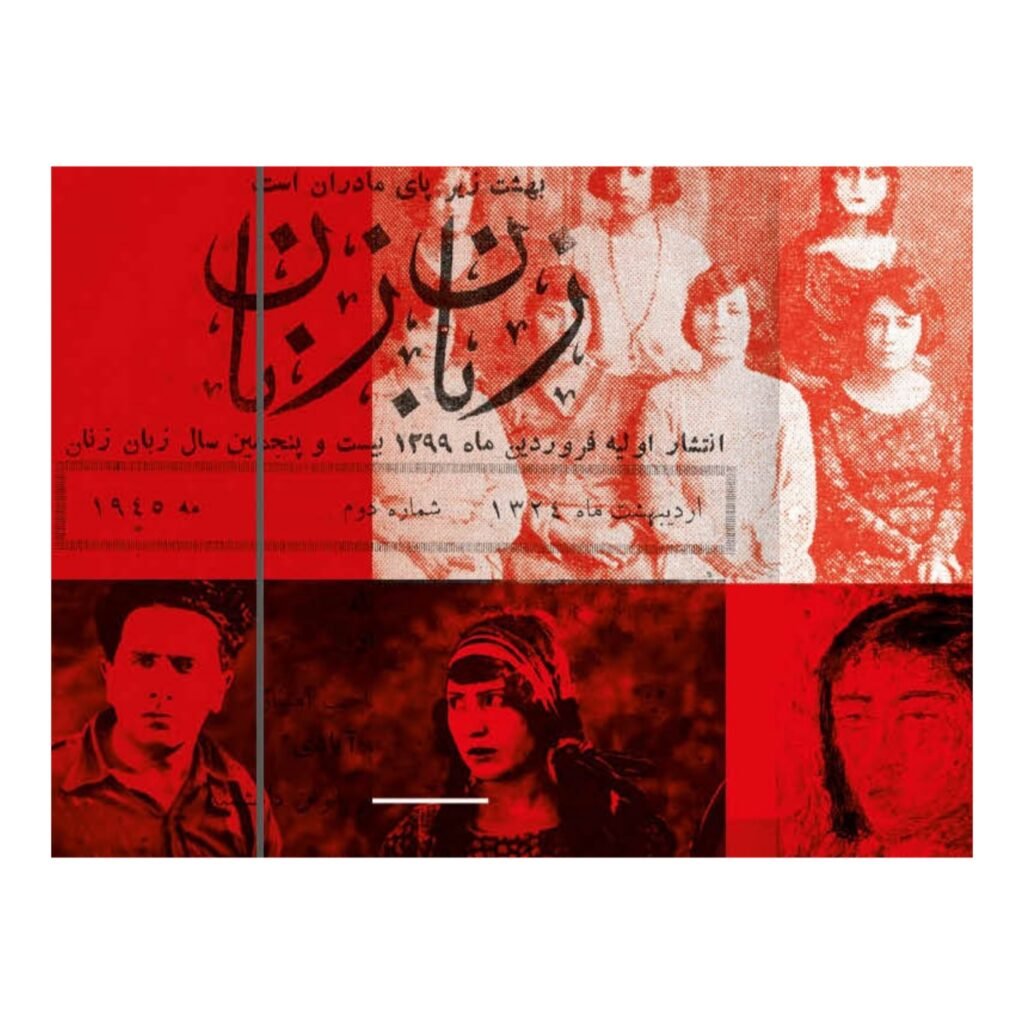

The war ended in November 1918. Russian and Ottoman army forces were forced to leave Iran, leaving the British unchallenged in the country. In 1919, Sediqeh Dowlatabadi published the magazine “Zaban-e Zanan” (Women’s Voice) in Isfahan. It was the first time the name of women was used in the title of a publication, and it stated that only articles written by women would be published. In the same year, the British sought to secure numerous concessions for their country through the 1919 agreement. Sediqeh Dowlatabadi, along with many intellectuals, sharply criticized this agreement. During this time, some people attacked the magazine’s office, accusing it of promoting unveiled women, and assaulted Dowlatabadi. “Zaban-e Zanan” was shut down. Subsequently, some of the attackers were identified, one of whom was a personal servant of the British consul. It appears that Dowlatabadi’s criticism led to the shutdown and the attack.

In 1923, the women of the “Jam’iyat-e Nesvan-e Vatankhah” (Patriotic Women’s Association) gathered in front of the police headquarters in Toopkhaneh Square, Tehran, and burned booklets titled “Women’s Deception” to protest the historically patriarchal literature. Motaram Eskandari stated, “This action is to defend the honor and dignity of your mothers and sisters. We women, like all humans, have intelligence and are not deceitful.” Through this symbolic protest, they aimed to voice their objection to the male-dominated discourse that restricted women. This action was a practical response to those who, on one hand, considered women as minors in need of men’s supervision and, on the other hand, labeled women’s intellect as deceitful.

In another incident, in May 1924, the “Patriotic Women’s Association” planned to raise funds for establishing a women’s literacy school by staging a home theater performance called “The Apple and Adam and Eve in Paradise,” featuring three Armenian actors. However, the event was severely disrupted when hooligans attacked the house where the play was to be performed, claiming that it was an action against societal norms. It was rumored, with the intent to provoke, that the play was organized to promote women’s unveiling. Following this incident and its repercussions, the association adopted more cautious methods.

Undoubtedly, over the past century to the present day, gender disputes have been at the core of the most significant political and civil conflicts in Iran. Should women step into public life or return to their homes? A conflict between the private and public spheres has unsettled Iranian society. One of the primary issues for Iranian women has been the patronizing attitude of men—men who have historically turned women’s presence and freedom into subjects of their sudden decisions, even when women of intellect and opinion were abundant. However, their independent opinions were intolerable.

A clear example of this confrontation with women was evident at the first Islamic Women’s Conference during Reza Shah’s era. Despite the presence of veteran members of the Patriotic Women’s Association and many intellectual women, a man, Sheikh al-Mulk Ourang, represented the government and practically steered the congress towards government policies. Most women from the Patriotic Women’s Association left the meeting, but the governor preferred to continue with his desired spectacle rather than acknowledge the opinions and active presence of genuine women’s rights activists.

The formal approach to the issue of women and women’s rights in Iran has rarely changed, except during brief periods of political breathing space. During the reign of the second Pahlavi, all political forces were eager to include women, but in some cases, they saw feminist tendencies as obstacles to women’s obedience and their integration into party ideals or patriotism. Women, except for individuals like Sediqeh Dowlatabadi or Mehrangiz Manouchehrian, had to compromise with their male party members, use feminine tactics, lower their voices, and show that they would adhere to being the second sex, both in politics and at home, in hopes of finding a way to dialogue with the male dictatorship.

It is no coincidence that Sediqeh Dowlatabadi, aware of this historical limitation, named her newspaper “Zaban-e Zanan” (Women’s Voice). It is also no coincidence that she was asked to rename her newspaper when it was shut down.

This name is a direct reference to what was condemned in the patriarchal culture of its time. Why do men fear the female voice? A century of women’s struggle has shown that the tolerance of the female voice in public space has been more frightening than the tolerance of the female body. The independent voice of women has never been recognized in any era. Yet, history is taking a different path. Today, despite a century of struggle, many of the most significant obstacles and problems for women remain unchanged, but new movements and models of struggle are following a different path.