With the rise of the Islamic Republic in the early 1980s, a different kind of resistance was taking shape in Iranian Kurdistan. This resistance was not limited to questions of ethnic identity or geography, but was an attempt to build a new kind of politics. At the center of this struggle stood Komala, which later became the Kurdistan Organization of the Communist Party of Iran. A leftist force that combined armed struggle with mass organizing. Mohammad Asangaran, one of the guerrilla fighters of that era, now lives in exile in Germany. Decades later, he still writes and reflects on the unfinished struggles of Kurdistan and Iran.

In this interview, Asangaran speaks with precision and clarity about the current state of Kurdistan: how economic poverty, political repression, and military securitization continue to define daily life for the region’s people. He emphasizes that while the people of Kurdistan suffer from national oppression, their fate is deeply tied to the broader crisis of the Iranian state. The 2022 Woman, Life, Freedom uprising, which began in Kurdistan, is for him a turning point—both symbolically and practically—in linking the Kurdish struggle with the rest of Iranian society.

The conversation continues with a discussion about the controversial term “occupation,” the changing roles of Kurdish parties in Iraq, and whether it’s still possible to speak of a unified Kurdish movement today.

Asangaran is clear: Kurdistan is not unified. There are deep ideological, class, and generational divides that fundamentally shape the political landscape. His analysis challenges both nationalist fantasies and simplistic interpretations from outside observers. What emerges is a picture of a society in motion; a society caught between state violence, political compromise, and a constant demand for freedom and justice.

This conversation is an invitation to understand the complexity of a movement that has never stopped resisting.

Your support helps keep this space alive but also ensures that these critical discussions remain accessible to all.

In the current situation, how can we describe the overall condition of Iranian Kurdistan in relation to Iran’s national crises—such as the economic crisis, political repression, and social uprisings?

Kurdistan, like other parts of Iran, is under the rule of a repressive, ideological, and corrupt government. Even though the culture and values of people in a country are not exactly the same, within a certain historical period, they are generally similar. But there might be some features in Kurdistan that show certain differences from other parts of Iran.

For example, in Iranian Kurdistan, people are relatively more politically organized.

They suffer from national oppression.

Their language is not taught in schools. A general feeling of national discrimination exists. Overall, the government sees this region as more of a threat than other parts of Iran, and a security-focused atmosphere can be felt everywhere. Repression is more intense, and the number of executions and arrests is higher.

At the same time, poverty, unemployment, and economic insecurity—except in Sistan and Baluchestan—are worse than in the rest of the country.

In Kurdistan, people have never had illusions about the Islamic Republic. They see the government as their enemy.

After the “Woman, Life, Freedom” uprising, what changes have occurred in the form and level of political participation in Kurdistan? Have you seen any divisions between different classes or generations?

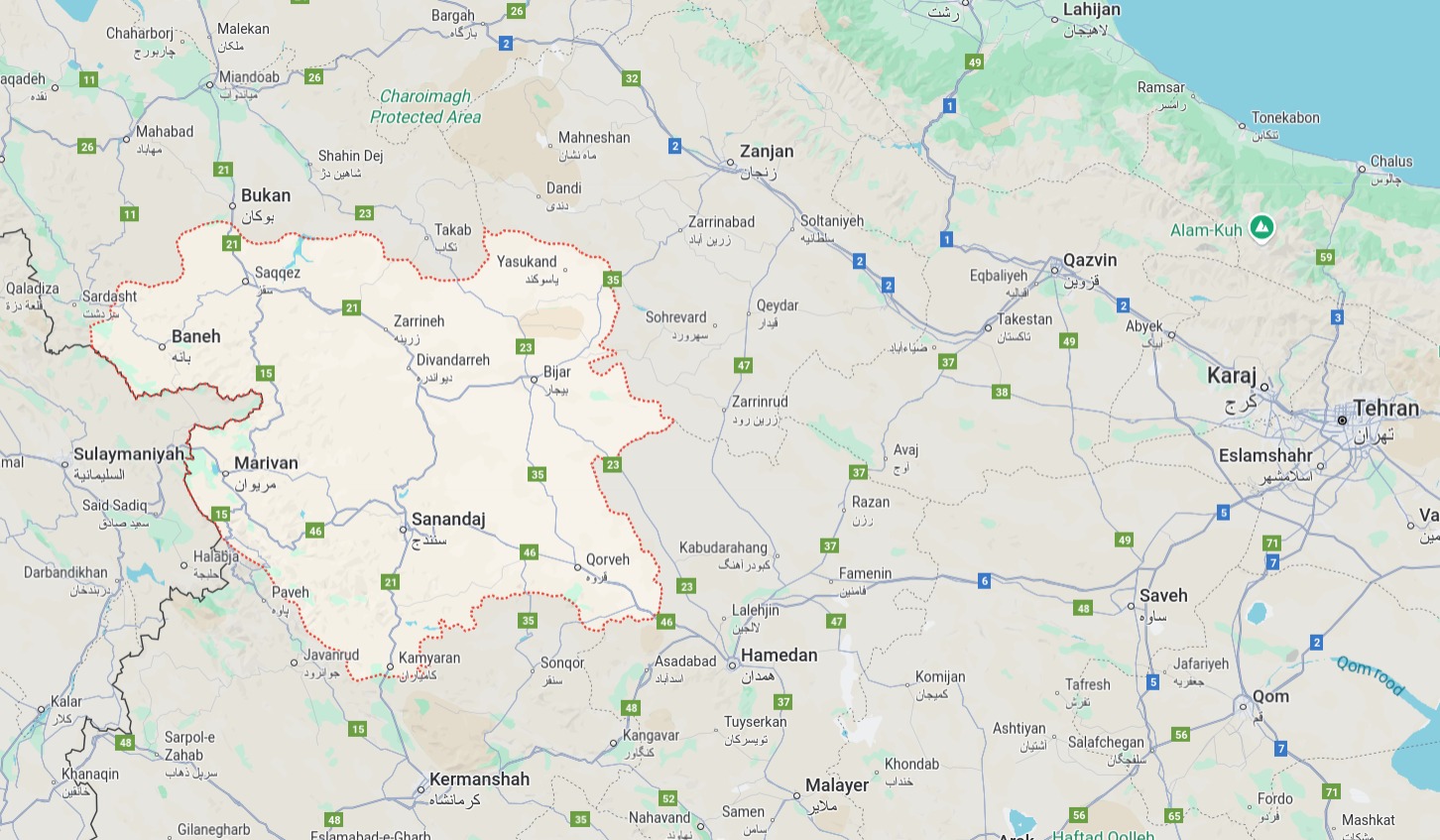

After the “Woman, Life, Freedom” uprising, the people of Kurdistan gained more self-confidence. This movement started from the city of Saqqez and then spread to other cities in Kurdistan before reaching the rest of Iran.

People in the rest of Iran felt more solidarity, sympathy, and unity with the people of Kurdistan than before. A sense of shared destiny with the rest of Iran reached its peak. In Kurdistan, there were several general strikes, and people participated in them on a mass level. These strikes happened after calls from political parties. Kurdistan’s parties have significant mass influence. Two strong mass movements exist in Kurdistan and compete with each other, but in some cases, they have acted together against the central government, issued joint calls, and received responses.

Communists and nationalists are clearly recognized in society. Their activists, parties, and strategies are distinguishable. Also, the different social classes—workers and capitalists—have concrete and material meaning for the people. Their politics, literature, songs, history, heroes, and values are different.

For example, Qazi Mohammad and Ghassemlou are known as heroes and leaders—and almost sacred—for the Kurdish nationalist movement. Fouad Mostafa Soltani and Sedigh Kamangar hold the same position for the leftist movement. The song “Ey Reqib” is fully recognized by the nationalists, and the “Internationale” is well known among the leftists.

At the graves of martyrs or on special days, these ceremonies—with the specific flags of these two movements—can be seen. International Women’s Day and Workers’ Day are known among the leftists with red flags and the Internationale anthem. Likewise, the anthem “Ey Reqib,” the Kurdistan flag, the anniversary of the Republic of Mahabad, and the founding of the Democratic Party are important and recognized by the nationalists.

However, the younger generation and the older generations have different cultures. Religion in Kurdistan generally has less influence compared to the rest of Iran.

But the young generation is very integrated with global culture, the internet, and social media. The worldview of this generation—known as Generation Z—is much more anti-religious and progressive than the previous generations.

Should the situation in Kurdistan be analyzed separately from the rest of Iran, or should it be seen as part of the general crisis of the Islamic Republic? Why?

It is clear that Kurdistan is part of the political, social, and economic system of Iranian society. The historical and cultural commonalities among the people of Iran are very deep and rooted. For centuries, they have lived together in the same geography. Over the last hundred years, all the ups and downs in Iran have been similar across the country. The only difference is the presence of national oppression and the Kurdish issue, along with the level of political organization—both of which are products of this same recent century.

But even during these hundred years, all people have dealt with the same government, policies, economy, and laws. These shared factors, along with the leftist social movement that has represented the shared fate and unity of the people of Kurdistan with the rest of Iran and has actively promoted this direction and policy, have managed to deepen the sense of common struggle and solidarity among the people.

Divisive nationalist and Islamist propaganda has not been able to weaken this feeling of shared destiny and closeness.

In your opinion, the concept of “occupation of Kurdistan” by Iran—which some groups emphasize—how real, symbolic, or political is it?

The term “occupation” is an old one. It entered the discourse of Kurdish nationalists after the suppression of the Mahabad Republic following World War II, and later appeared in the discourse of monarchist nationalists after the fall of the Shah.

In both cases, it is directly related to political developments in Kurdistan and Iran.

In Kurdistan, the Shah’s military campaign to crush the Mahabad Republic and execute Qazi Mohammad and his companions popularized this term. Later, during Khomeini’s military invasion to suppress the Kurdish people in the early 1980s, the term gained a broader meaning. In practice, the term referred to military forces that were not local—sent to brutally suppress an active movement. They used a language foreign to the people of the region and were seen symbolically as outsiders.

But from the early 1990s, this language became less common and more marginal, as the armed struggle declined and people in Kurdistan—like the rest of Iran—were mainly facing a corrupt religious government with all its repressive forces, not a military army with tanks and guns.

Today, the ones using this term are Kurdish ultra-nationalists and pro-Western Iranian ultra-nationalists. But they represent two different political goals. Still, the term hasn’t gained serious traction among the general public and is not commonly used.

Kurdish ultra-nationalists who use the word “occupation,” such as PJAK, also say that their strategy is not to overthrow the Islamic Republic. Their goal is to “democratize” it. They are open to negotiation and co-existence with the regime. Their class and cultural differences with the regime are not significant. Their main issue is that the regime does not legally allow them to operate or share power.

In a recent interview, Amir Karimi, one of PJAK’s leaders, told BBC Persian that they are ready to negotiate and compromise with the Islamic Republic—but the regime refuses to talk with them.

Their concern is not really about the rights of the Kurdish people. Like the PKK, their problem is that the central government does not share local power with them. They want a share of political power—similar to what is happening now in Iraqi and Syrian Kurdistan.

In those places, class divisions, exploitation, poverty, repression of dissent, and lack of public participation in shaping politics and destiny are very similar to parts of Kurdistan where Kurdish parties are not in power. In reality, the rulers and decision-makers in Iraqi and Syrian Kurdistan are Kurdish-speaking elites from the owning classes—while in Turkey and Iran, they are Turkish-speaking and Persian-speaking elites.

But the political, economic, and social systems ruling these societies are still the same: a brutal capitalist and exploitative system. The ruling Kurdish parties in Iraqi and Syrian Kurdistan follow the same economic and political model. From this angle, there is no fundamental difference between their system and the one supported by Erdoğan or Khamenei. The conflict of Kurdish nationalist parties is about getting a share of power from these states—not about the basic rights of the Kurdish people.

What role does the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in Iraq play in regulating or limiting the activities of Iranian Kurdish parties? Especially in recent years, how has it acted?

The ruling parties in Iraqi Kurdistan have held a share of political power in Iraq since the 1990s.

This power-sharing means they are part of Iraq’s central government. Politically and economically, their interests lie in being part of the broader bourgeois power structure. In terms of regional rivalries, Barzani’s party is aligned with Erdoğan in Turkey, while Talabani’s party is closer to the Islamic Republic of Iran. Although they compete with each other, they also belong to two rival regional blocs. Barzani’s area of influence borders Turkey, and Talabani’s borders Iran.

However, because of the Islamic Republic’s strong influence in Iraq and the Shi’a majority there, the Kurdish parties in Iraq are forced to maintain deals and compromises with Iran. Iran’s influence is not only military but also comes through pressure on the central Iraqi government. On the other hand, Turkey imposes its influence mainly through military power, economic ties, and its close alliance with Barzani’s party.

As a result, Iran has managed to dictate its policy to the ruling Kurdish parties in Iraq using both its military strength and its leverage over the Iraqi government.

This has enabled the Islamic Republic to push forward its policy of disarming and limiting the activities of Iranian Kurdish opposition parties based in Iraqi Kurdistan.

The Iranian Kurdish opposition groups—such as Komala, the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan, PJAK, and others—are mostly based in areas under the control of Talabani’s party.

The Islamic Republic has almost complete control in this area. It has signed a security agreement with the central Iraqi government that requires Iranian opposition groups to be disarmed and kept away from the border zones between the two countries.

The Kurdish ruling parties in Iraq are now forced to enforce this policy.

Today, the Iranian Kurdish opposition groups based in Iraqi Kurdistan have been disarmed and are under tight control by the local Kurdish authorities.

PJAK, however, has not been disarmed and is not under the same pressure. That is because since 2011, the PKK and PJAK have not only maintained a ceasefire with the Islamic Republic, but they also reached and implemented an informal deal.

That year, Assad in Syria was under pressure, and the Syrian army withdrew from Kurdish areas and handed them over to the PKK.

On the Iran-Turkey-Iraq border, a ceasefire between the Islamic Republic and PKK/PJAK was implemented, and cooperation between Iran’s Revolutionary Guards and PJAK/PKK forces has continued ever since. Their bases are located side by side near the Iran-Iraq border, with only small distances between them.

PJAK and PKK have committed not to allow any armed group to enter Iranian territory through those areas.

The armed clash a few years ago between PJAK/PKK and the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan near Sardasht and Piranshahr happened for this reason.

In recent years, a large part of PKK forces stationed in Qandil were relocated to areas near the Iran-Iraq border, such as Penjwen, Mariwan, Uraman, and Sardasht.

This move was meant to protect their forces from Turkish drone strikes and air attacks.

That’s why, in the past year or two, there have been Turkish drone operations near Penjwen and Sulaymaniyah.

If the negotiations between Turkey and Öcalan succeed, one possible outcome could be a closer relationship between Barzani and the PKK, as well as between parties close to the PKK like PYD in Syrian Kurdistan and PJAK in Iranian Kurdistan.

Even in the past few weeks, we’ve seen renewed contact between the PKK and Barzani’s party, and growing coordination between ruling parties in Syrian Kurdistan and those aligned with Barzani in this region.

Can we speak today of a single, unified “Kurdish movement,” or are we dealing with a diverse set of different political projects?

Kurdish nationalist parties—except in Iranian Kurdistan—have an uncontested role in Kurdistan of Turkey, Syria, and Iraq. But these parties have never been united. That’s because each of them is tied to a different state in the region based on their own interests. Traditionally, such parties have either been supported by one regional state to fight against their own state, or they have entered into negotiations and power-sharing deals with their own governments. In some cases, both of these strategies have happened at the same time.

Besides this, Kurdistan, like all other societies, has different social classes, political movements, and traditions. Leftist, right-wing, centrist, liberal, Islamic, nationalist, and communist parties and movements all play roles in Kurdistan according to their capacity and influence.

We do not have a uniform society where we can expect to have one single type of party. In a class-based society, there are naturally different movements and parties with different goals and strategies—and Kurdistan is no exception.