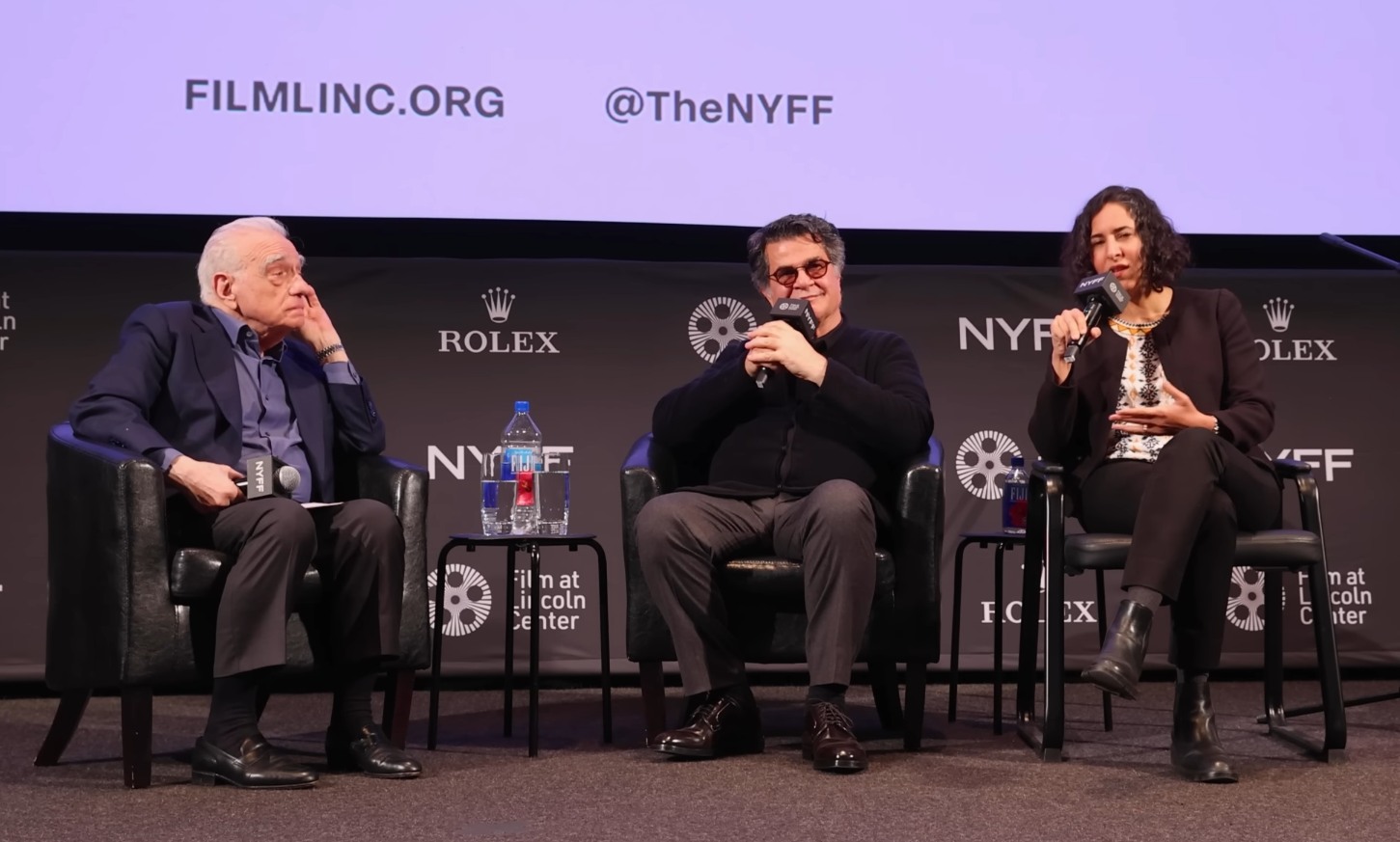

At an event held in honor of courageous, resilient cinema, Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi and legendary director Martin Scorsese sat down for a deep conversation about obstacles, inspirations, and the power of film under extreme restrictions. The talk, in New York, gave Panahi space to speak about the roots of his passion and how a 20-year filmmaking ban pushed him toward new forms of storytelling.

Panahi traced his stubbornness to a working-class childhood and a father’s command never to bow. When a 20-year ban tried to turn that command into silence, he answered with form: first the provocation of This Is Not a Film, then the street-level confession of Taxi. Half the labor, he says, is learning to think like a thief—moving sets, hiding rushes, trusting villagers, and letting humor disarm fear so the last blow of truth lands harder.

The city he films has changed. After “Woman, Life, Freedom,” unveiled and veiled women stand side by side. He won’t recostume reality. Superstars who stood with the streets were faded out by censors; crews worked through threats; at Cannes, actresses went without hijab anyway. Exile remains a fact of Iranian cinema, but Panahi refuses it. He stays, betting on a new generation that will not accept any censorship.

His latest ending is an eighteen-and-a-half-minute act of faith. It leaves one question hanging over the credits: will we carry this cycle of violence into tomorrow, or finally cut it?

Your support helps keep this space alive but also ensures that these critical discussions remain accessible to all.

A groundwork of labor and resistance: Panahi’s class roots

Opening the conversation, Scorsese praised the “very strong and great” risks Panahi faces, along with his passion, “remarkable flexibility, and courage.” Panahi responded by recalling his childhood in a working-class neighborhood; his father was a laborer who died at 53 while painting numbers on a machine at the factory, in front of other workers. His father used to tell him: “Son, you must never bow to any power except God.”

Because there were no leisure facilities where he grew up, their only fun was pooling pocket money, skipping school, and watching commercial crowd-pleasers. There was, though, a children’s cultural center library that screened short, unusual films by directors like Mr. Beyzai and Mr. Kiarostami. Panahi stressed that he and his neighbors never saw such films in local theaters; the library was their only access point.

His first experience with a camera came as a child, when—because he was “chubby”—he was invited to act in a film. During the shoot, a simple story about a children’s game, he kept eyeing the camera, wanting to see the world through the viewfinder, but the cinematographer never let him. That curiosity to look at the world through a lens pushed him to save money, buy a still camera, and start working.

Apprenticeship with Kiarostami: the blindfold lesson and a different gaze

After university and a few short films in remote centers, Panahi returned to Tehran. He heard that Mr. Kiarostami was preparing a new film, left a message on his machine, and asked to learn from him. Kiarostami liked the tone of the message, and Panahi joined the crew on location in northern Iran.

On day one, as an unknown face on set, Panahi heard the crew say they couldn’t work that day. Eager to prove himself, he stepped up and promised to have the set ready by 4 p.m.—and he did. This earned Kiarostami’s trust, and Panahi became assistant director.

Panahi shared a striking memory: one day Kiarostami put him in a car, handed him a blindfold, and told him to wear it. After a drive down a dirt road, they stopped, walked a bit, and Kiarostami told him to remove the blindfold. Panahi looked out and saw the final shot of Through the Olive Trees, designed so that people in the distance would appear very small.

On these trips Panahi noticed a difference in their worldviews: Kiarostami naturally faced the landscape, while Panahi was drawn to people. That difference shaped Panahi’s work into what he calls “social films.”

Turning a ban into invention: This Is Not a Film and Taxi

Scorsese noted how harsh restrictions forced Panahi, with “flexibility and ingenuity,” to invent new cinematic forms and tell stories differently.

Panahi agreed. When he was told he could not make films, give interviews, write, or leave the country for 20 years, he was shocked. Students who found the conditions suffocating would come to him and “complain a thousand times.” He realized the ban could become a perfect excuse not to work, but he chose not to be trapped by it. He looked for solutions and, with Mojtaba Mirtahmasb, began This Is Not a Film. “We named it This Is Not a Film to say: we looked for a way.”

At his lowest, he thought: if he couldn’t make films—and since he’s a “clumsy guy” who knows no other job—he might as well drive a taxi. Then it hit him: even then, he’d be tempted to mount a camera and film people’s stories. That idea became Taxi. After Taxi, the chronic complainers stopped coming; they saw they had to find their own ways too.

Filming underground: thief’s thinking and humor as a cultural shield

Panahi emphasized that under such conditions about 50% of a filmmaker’s energy goes into figuring out how to work at all—a mindset he called “thinking like a thief,” or like a guerrilla.

He described the practical hardships: for one project (likely No Bears, though he didn’t name it), they had a full script and remote locations in a village that was hard to access for security forces. They even posted someone on the road to warn them if a stranger approached. Still, on day six, intelligence agents raided the village. Locals hid Panahi, and from then on the crew had to move to a new village for each shot.

Panahi also stressed the role of wit and humor in his films—a mix of cultural instinct and playful mischief. He recalled a childhood friend who planned to commit suicide and kept rejecting small cars for the attempt, a dark, absurd detail that shows how “tickles of humor” can help people endure despair. Scorsese agreed that the humor in Panahi’s latest film disarms the audience and makes the last 15 minutes—packed with truth and force—land even harder.

All the energy on the ending: truth in 18 and a half minutes of silence

Panahi said he always focuses intensely on openings and endings. The opening “insures” the viewer; the ending must stamp the truth. In his recent film (with the main character tied to a tree), he felt during the shoot that he didn’t “recognize” the actor—because the character had been absent for most of the film, kept inside a trunk. He decided the final shot had to be an 18.5-minute medium shot demanding exceptional acting.

The first night failed. Stressed by the stakes, he turned to a friend who had spent a quarter of his life in prison and had helped write the film’s dialogue. With this friend’s help, he mapped when a man under pressure asserts power, when he laughs, when he humiliates. Scorsese praised the film’s rhythm and the lead actor’s astonishing performance—especially the long silence and his final line, “I just wanted to feed my children.” Panahi revealed that in that charged moment, the entire crew behind the camera was in tears.

“Woman, Life, Freedom” and filming a society as it is

When No Bears screened in Venice, Panahi was in prison. After his release, he found that “the city’s face had changed”—the Zan, Zendegi, Azadi (Mahsa) uprising had begun. He called women’s resistance unprecedented: they crossed a “red line” once thought unimaginable. In his view, the history of the Islamic Republic is now divided into before and after the Mahsa movement.

These profound social changes shaped his latest film. Before the uprising, you almost never saw women without headscarves in the streets; now veiled and unveiled women stand side by side. He could not film that reality and show everyone veiled.

He gathered his cast, asked them to read the script, think for 24 hours, and decide—on the condition they tell no one. All agreed freely.

During a semi-clandestine shoot, a woman recognized him. He asked her to appear in a scene. She told him plainly: “Mr. Panahi, if you tell me to wear a headscarf, I won’t.” He stressed that this freedom was not granted by the state—women seized it themselves. Many superstar actresses, at the height of their fame, removed their headscarves in solidarity and were pushed out of the industry.

He also confirmed that his actresses attended the Cannes festival without hijab—despite prior threats from intelligence agents—and took part in the entire program.

The future of Iranian cinema: exile and a new generation of refusal

Panahi noted that forced migration and exile have been part of Iranian cinema since the revolution. Great artists—Behrouz Vossoughi, Parviz Sayyad, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Amir Naderi, Asghar Farhadi, Bahram Beyzai and others—now live abroad or do not make films in Iran. He misses the films they could have made at home.

Unlike some who can adapt to working abroad, Panahi admitted he doesn’t have the “nerve or courage” to stay outside. He has chosen to remain and work in Iran. He’s optimistic about young filmmakers who follow his path and refuse any form of censorship. He expressed concern that Mohammad Rasoulof recently had to leave Iran to finish post-production abroad, but Rasoulof is determined to return.

Scorsese closed by saying international platforms and festivals must support such films. Cinema can be incredibly powerful, he said, comparing its impact to Italian neorealism, which helped restore people’s hearts and spirits after World War II.

The final question: will the cycle of violence continue?

In closing, Panahi explained the core idea behind his latest film’s ending: he wants the viewer to leave with one question—will this cycle of violence continue in the future, or not?

Justice and forgiveness appear in the film, he said, but only as drivers of the story. The film is made for the post–Islamic Republic period, to make us think now about what comes next—and perhaps decide not to carry the violence forward.

He called the conversation, and the chance to have it, a great honor.

I am fan of the iranian cinema, and have seen all the films of many directors, especially the distinguished ones. Panahi is of my favorites.

https://www.elaliberta.gr/πολιτισμός/κινηματογράφος/10504-ο-κινηματογράφος-του-παναχί-και-η-τέχνη-της-παράνομης-διάδοσης-της-αλήθειας-siyavash-shahabi