There are moments when political confusion doesn’t just disorient you—it makes you feel betrayed. As an Iranian writer and activist in exile, I have spent years trying to understand not only the regime I escaped, but also the silences and excuses that surround it. I have watched with disbelief as many people—especially those who identify as anti-imperialists—express support or neutrality toward regimes like Assad’s in Syria or Khamenei’s in Iran. The same regimes that torture students, shoot protesters, jail workers, and execute women in public. All of this, ignored or minimized, simply because these regimes say they oppose the West.

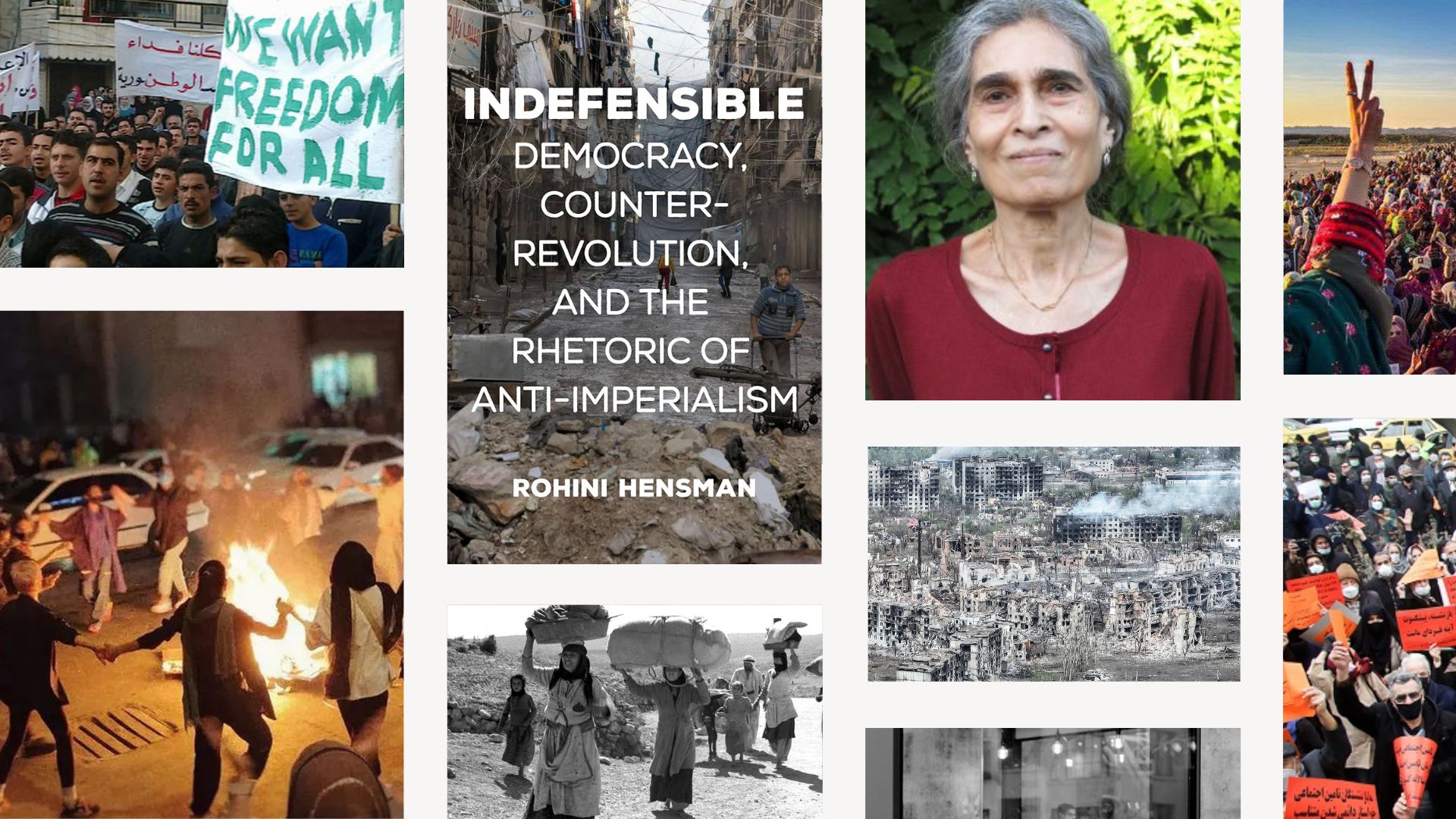

In that confusion, I came across Indefensible: Democracy, Counter-Revolution, and the Rhetoric of Anti-Imperialism by Rohini Hensman. It was not just another left critique. It was, for me, a political lifeline. The book begins with a simple but courageous premise: that the left’s support for authoritarian regimes under the banner of “anti-imperialism” has become one of the great moral and strategic failures of our time.

Published in 2018, Indefensible reads like a map of political self-rescue. With clarity and insistence, Hensman takes us through some of the most misrepresented struggles of recent history—from Syria and Ukraine to Bosnia, Iran, and Iraq—and shows how so much of the global left has ended up siding, whether explicitly or through silence, with counter-revolution. At the heart of her critique is what she calls “pseudo-anti-imperialism”: a worldview that sees U.S. empire as the only real enemy, and automatically absolves any force that claims to resist it, no matter how brutal or reactionary.

But Hensman’s book is not just a critique—it’s also a re-grounding. A Sri Lankan socialist and feminist based in India, she brings to this work the experience of having lived through the collapse of revolutionary hopes and the betrayal of democratic movements—not in abstraction, but in flesh. Whether speaking of Tamil resistance and state violence in Sri Lanka, the rise of Hindutva in India, or the crushing of popular uprisings in the Arab world, she insists on a kind of internationalism rooted in solidarity with people—not states, not factions, not slogans.

I contacted her because I needed clarity, and because Indefensible gave me more than analysis—it gave me a political language that didn’t force me to choose between resisting imperialism and defending human dignity. In our conversation, she spoke with the same urgency and honesty that fills her book. What follows is not only an account of that dialogue, but an attempt to continue the political task Indefensible began: to reclaim anti-imperialism from those who’ve turned it into a mask for authoritarianism—and to return it to those fighting for democracy, freedom, and life itself.

What prompted you to write Indefensible, and what do you hope leftists take away from it, especially those who continue to support authoritarian regimes in the name of anti-imperialism?

I welcomed the uprising in Syria along with all the other Arab uprisings, and was alarmed at the degree of repression that it met from the Assad regime. What disturbed me most of all was that by contrast to protests against, say, Israeli assaults on Palestine, protests against the brutality of the Assad regime and its allies – Hezbollah, Iran, Iraqi militias and Russia – were hardly seen anywhere.

Watching Al Jazeera coverage of the slaughter in Aleppo combined with the lack of outrage from the left literally made me ill, so I started writing as a way of expressing my solidarity with the struggle of Syrians for dignity and democracy. But as I wrote, I discovered that the failure of large sections of the left on Syria was part of a much larger problem, and so it turned into a book analysing what I called ‘pseudo-anti-imperialism,’ taking up cases of it in Russia and Ukraine, Bosnia and Kosovo, Iran and Iraq as well as Syria.

Basically, their vision of the world was West-centric and Orientalist; they failed to see that ordinary people in other parts of the world like Libya and Syria had agency and the desire for democracy, so they clubbed the democratic uprisings in these countries with the US-led invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. I contrasted this with genuine anti-imperialism, which opposes all imperialisms and supports all democratic revolutions.

My hope was and is that socialists who read it will understand that opposing only Western imperialism and failing to express any solidarity with people struggling against other imperialisms or authoritarian regimes is a betrayal of socialist values.

You challenge a significant strand of the left that sees any enemy of the U.S. as inherently progressive. What historical or theoretical missteps do you think led to this distortion?

I trace this tendency back to the degeneration of the Russian revolution and the failure of much of the left to come to terms with it. Of course, the Russian revolution took place in dire circumstances and would inevitably have faced huge problems, but a principled commitment to democracy on the part of Russian leaders would have saved it from becoming the authoritarian and imperialist monster it became.

Lenin played an ambiguous role. On the one hand, he encouraged an enormous centralization of power in the hands of the Bolshevik Party, which allowed the most totalitarian elements to take control of it, while his failure to allow the Constituent Assembly to do its work resulted in the state becoming an amalgam of bourgeois and Tsarist elements, as he himself acknowledged shortly before his death. On the other hand, Lenin hated what he called ‘Great-Russian chauvinism,’ by which he meant ethnic Russian supremacism and imperialist domination of former Tsarist colonies.

For him, Russian imperialism had to be opposed in exactly the same way as Western imperialism. He clashed with Stalin on this point and tried to ensure that the constitution of the USSR would allow for equality between Russia and its former colonies.

After Lenin’s death, Stalin reversed his policies but didn’t change the constitution, because he wanted to present himself as Lenin’s true heir. Yet hardly any Communists and fellow-travelers, nor even Trotskyists and other anti-Stalinists, highlighted his oppression of former colonies. A few anti-Stalinists denounced his 1939 pact with Hitler, which also had an imperialist dimension, but most continued to call the Soviet Union a workers’ state, and for mainstream Communists it was a socialist country.

So Western and especially US imperialism was the main enemy. Anyone who posed as an opponent of US imperialism, even if too brutal and authoritarian to be characterized as progressive, could hope to evade scrutiny and condemnation of their crimes.

You group together figures like Putin, Khamenei, Assad, Netanyahu, Trump, and even al-Baghdadi—not despite their ideological differences, but because of their shared contempt for human rights and democracy. What do you think explains the growing affinity between far-right movements and authoritarian states across such seemingly different ideological and cultural contexts?

Autocrats may call upon a variety of ideological or religious beliefs to back their claims to absolute power, but their agenda remains the same: to negate human rights and crush democracy. If they come from a Muslim background, like Khamenei and his predecessor Khomeini, or al-Baghdadi and his successors, they use their own somewhat different visions of Islamic supremacism; Netanyahu appeals to a Zionist vision of a Jewish-supremacist state; Putin goes back to the greatness of the Tsarist empire and Russian supremacism; Assad pretended to be secular but favoured his own Alawite community and persecuted Sunnis; Trump’s ideology is White-supremacism in tandem with unhindered capitalist exploitation and corruption.

But they all seek to wipe out dissidence or resistance to their executive actions, moulding state institutions to conform to their dictatorial inclinations. Once in power, they make it almost impossible to remove them. In rare instances, the strength of pre-existing democratic institutions and popular beliefs may stand in their way, as in the case of Trump, or the patent incompetence and corruption of their regime may lead to its collapse in the face of a minor push, as in the case of Assad.

How should we understand the alliances of convenience among authoritarian regimes—whether secular, theocratic, or populist—when they all oppose popular uprisings and democratic revolutions?

In a way, you have answered your own question: they form opportunistic alliances with groups and regimes that appear to be completely hostile because they have a common interest in crushing democracy. The United States and Islamists in Iran appear to be on opposite sides, and you would think there’s been no room for wheeling and dealing. Yet they have collaborated on numerous occasions.

The 1953 coup against secular, democratic Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh was orchestrated by the CIA and MI6, but approved by Khomeini and carried out on the ground by Islamist mullahs and knife-wielding gangs. When over 50 US citizens were taken hostage in their embassy in Tehran in 1979, it was a huge embarrassment to then-president Carter, who had been critical of human rights abuses by the Islamic regime.

His failure to get the hostages released ensured he lost the next election to Reagan, who had no such qualms about human rights. In a highly significant move, Khomeini released the hostages on the day of Reagan’s inauguration. Documents unearthed by Robert Parry and reported in an article entitled ‘When Israel/Neocons Favoured Iran’ show that Israel’s Likud government of Menachem Begin became an important source of covert arms supplies to Iran after Iraq invaded Iran in 1980, with the profits being invested in Jewish settlements in the West Bank.

The Israeli Labour Party’s desire to get in on this act paved the way to the Iran-Contra scandal in 1985–86, when Reagan authorized the secret sale of anti-tank and anti-aircraft weapons to Iran via Israel and used the proceeds to fund the Contra terrorists in Nicaragua. By this point, Saddam Hussein had long been calling for a ceasefire and negotiations in the Iran-Iraq war, but Israel regarded him as their greatest enemy and wanted him defeated, and American neocons agreed.

So you had Iranian Islamists, Israeli Zionists and American neoconservatives all on the same side, despite huge ideological differences. More recently, in response to the Syrian uprising in 2011, Assad not only released around 1500 well-connected Islamists from its prisons but actually gave them arms and facilitated the influx of foreign Islamists.

Finally, it has just been reported that Israel-backed militias linked to ISIS are being allowed by the IDF to loot the miserable amounts of aid sent to Gaza.

Your chapter on Iran details the tragic alliance between some Marxist groups and the emerging theocracy. Do you see parallels in current leftist support for Iran’s regime? What lessons are still being ignored?

I would like to answer your question by referring to an interview with Chahla Chafiq in Jacobin, since her political positions are so close to mine but she was a participant in the Iranian revolution whereas I was not. She explains that the Tudeh party was the classic pro-Soviet party and the Fedayeen guerilla movement also aligned with the Soviet Union although less so, whereas she belonged to ‘Line Three,’ the independent left, which believed that the Soviets were an imperialist force.

The Soviet-aligned parties supported Khomeini because they believed he was anti-imperialist, because he referred to the United States as ‘Big Satan’ and Western Europe as ‘Small Satan’. But all the left groups agreed on the anti-Western-imperialist line, so even the independent left was confused. Feminism was seen as Western and rejected by the left, which thought that any problems of women’s rights, civil rights or human rights in general could be fixed by socialism: a position that Chafiq in retrospect thought was the biggest error.

When American feminist Kate Millet, who had worked with a group of Iranian dissenters campaigning against the Shah, visited Iran soon after the 1979 revolution in response to an invitation by Iranian feminists and joined a women’s March 8th demonstration protesting against compulsory veiling, she was vilified by pseudo-anti-imperialists in Iran as well as the US, saying, ‘What right do you have, from what position are you speaking?

We’re anti-imperialists.’ To me, this borders on insanity. Millet worked in solidarity with the people of Iran against the Shah, who was installed in a CIA-sponsored coup: doesn’t that make her anti-imperialist? But no, she’s not anti-imperialist according to these pseudo-anti-imperialists because she also demonstrated in solidarity with Iranian women! Similarly, any expressions of solidarity with Iranian workers, ethnic minorities or LGBT+ people makes you pro-imperialist according to their definition!

Independent socialists like Chafiq have learned from the dire consequences of the mistake they made, but much of the international left has not moved on. They were more outraged at the killing of Qasem Soleimani, a mass murderer, than the killing of thousands of peaceful protesters: more in solidarity with the oppressive regime than the people oppressed by it. They are still stuck in Stalinist Cold-War narratives, where Western imperialism is the only enemy and anyone claiming to oppose it deserves solidarity, no matter how despotic they are.

They constantly question or deny the agency of the amazingly courageous people who risk everything to struggle for freedom from such despotism, suggesting, for example, that Iranians fighting for democracy are either monarchists or are being manipulated by the West.

Your support helps keep this space alive but also ensures that these critical discussions remain accessible to all.

You mention that the Islamic Republic has exported its right-wing jihadi project while being framed as part of the ‘Axis of Resistance’. How do you interpret this contradiction within leftist internationalism?

I think the expansionism of the Islamic Republic has been most damaging in Iraq and Syria. Saddam Hussein invaded Iran only after the Khomeini regime made it clear they wanted to overthrow him, and was ready to negotiate a compromise two years after the start of the war, but Khomeini kept it going for six nightmare years longer at the cost of over a million lives because he wanted to annex Iraq.

There is a good chance that without those extra years of war, the US never would have gone to war against Iraq twice, and the Iraqi people themselves would have had a chance to deal with the despotic Saddam regime. Instead, George W. Bush fulfilled Khomeini’s dream by overthrowing Saddam, and the Islamic Republic became entrenched in Iraq thanks to the ignorance and incompetence of US proconsul Paul Bremer.

Teheran’s tight control of Iraq through its pro-Iran militias has led to economic crisis despite high oil revenues, and also massive corruption, bloody assaults on peaceful protesters, and a catastrophic attack on the rights of women and girls. The IRI’s intervention in Syria was equally destructive, starving and butchering civilians struggling for democracy and freedom from torture and mass graves in order to keep Assad as the figurehead of a regime they wanted to control.

But the pretence of being the head of an Axis of Resistance against Israel and the US shields the IRI from condemnation for all this from most of the left, who also show a complete lack of solidarity with the victims struggling for self-determination in Iraq and Syria. They don’t realise that by undermining international law in Iraq and Syria, they help Israel to demolish international law in Palestine.

Figures like Shapour Bakhtiar warned of fascism in clerical garments. Do you think it’s useful or even necessary to use the term ‘fascism’ when describing today’s Iranian regime?

Bakhtiar was prescient, his warning should have been taken seriously by the Iranian left. The Islamic Republic displays the essential features of a fascist regime, with its ethno-religious ultranationalism, extreme social conservatism and complete negation of democratic rights and freedoms.

Chahla Chafiq, who agrees it is a fascist state, described how it is much worse than the Shah’s regime, where despite censorship some freedom of expression was allowed, whereas there are ‘zero liberties and complete censorship’ in the IRI. The Shah’s secret police were identifiable, whereas Islamist surveillance is everywhere, in every workplace, university and social space.

And any departure from the ruling ideology is punished with arrest and incarceration as political prisoners, who are sought to be broken through rape and torture, including threats to family members, and executed in large numbers without anything resembling due process. The complete integration of the military in the form of the IRGC into both the state and the economy adds to the totalitarianism of the system.

Chafiq said that outsiders think that because there are elections, it is not a completely totalitarian system, and they also point to the presence of women in civil society, but she compares that to crediting the bacteria or virus for the body’s immune response, instead of seeing that it is women’s resistance to being shut up in the home that has allowed them to be present in civil society.

I recently watched a very good Iranian film called ‘The Seed of the Sacred Fig,’ which is set during the Woman, Life, Freedom movement and illustrates how the system works, making even friends and family members informants. It was smuggled out of Iran, and presents a sensitive and nuanced view of a middle-class family in which the man works for the state.

I would say that it portrays a state that is fascist through and through, if we abandon the overly narrow definitions of fascism that some Marxists have.

You speak strongly as a feminist against regimes like Assad’s or Khamenei’s. Why do you think parts of the left have remained silent or complicit in the face of gendered violence committed by these governments?

The left as a whole pays more lip-service to feminism now than it did when I was young, when we got criticized for dividing the working class by raising issues like women’s equality, which they said would be handled after the revolution. I think parts of the left have genuinely moved on since then, but in a rather patchy way.

Even today, the left remains male-dominated, with male theoreticians given more importance than women who are far more impressive and innovative. For example, on the issue of domestic labour, I would say that women have made the most significant theoretical contributions, and Black women have contributed massively by introducing the notion of intersectionality, yet they are often treated as less worthy of respect than mainly white male theorists.

Another problem is the failure to distinguish between state and people, the fear that if you criticize the state in Syria or Iran, it will be taken as a green light for your own government to bomb the people or impose sanctions that hurt them. The Assad regime systematically used rape as a weapon of war, not only against women and girls but also to a lesser degree against men and boys, but somehow talking about this was seen as asking Western governments to bomb Syria.

When Iranian women and girls burn their hijabs and chant ‘Death to the dictator,’ their willingness to risk their lives is seen as a possible sign of manipulation by ‘outsiders’. There is a failure to listen to what the oppressed people – in this case the women and girls – are actually demanding by way of solidarity: at least honest reporting on the horrors taking place, their own demands, and possibly help with self-defence.

Finally, there is the problem of Orientalism, that affects even well-intentioned feminists in the West, who stand up for the right of Muslim women to wear the hijab in their own countries without seeing the millions of Muslim women fighting for the right not to wear the hijab, to have a choice about what they wear or don’t wear. ‘They’ are seen as not having the same desire for democratic rights and freedom from oppression that ‘we’ take for granted.

You point to a failure of empathy among some leftists—especially in India—to identify with democratic uprisings abroad. How much of this do you attribute to residual colonial mentalities or racialized thinking?

The majority of socialists in India share the same dismissive – one might even say contemptuous – attitude towards democracy, and that is the main reason why they fail to identify with democratic uprisings abroad. One exception is the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) Liberation, which also takes the issue of democracy in India itself more seriously.

It saluted the women leading the ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ movement as torch-bearers in the struggle against theocratic tyranny, while also making it clear that they opposed Western intervention. This was the position taken by socialist feminists in India, who did their best to send messages of solidarity to the uprising.

In the West, however, I do think what I called Orientalism and what you call residual colonial mentalities or racialized thinking plays a role in the failure of socialists to empathize with democracy uprisings in other countries, especially those that were formerly colonies. They see the revolution as centered in the ‘heartlands of capitalism,’ namely the West, and what happens in our countries as being less important.

Therefore the enemies of their own state, even if they are criticized as being oppressive, are not seen as their own enemies. This is a failure of internationalism based on a lack of understanding of capitalism as a global system. Socialism in one country or even one continent while capitalism thrives in the rest of the world is impossible – it will either be overthrown or subverted, as occurred in the Soviet Union.

You won’t have a socialist revolution in the West until workers in the former colonies are ready to participate in running the global economy and government, and that won’t happen without democratic revolutions in these countries.

In your experience, how has the Indian left historically framed the concept of international solidarity? Has that framing changed with developments in Syria, Iran, or Ukraine?

In a very general sense, the Indian left has displayed solidarity with anti-imperialist struggles by Third World countries. Where the lines are not so clear-cut – as in the case of Syria, Iran and Ukraine – many of them get confused. In Syria and Iran, for example, the claim that these states are part of an ‘Axis of Resistance’ against Israel and the US has deterred this section from offering any solidarity whatsoever to their victims in Syria, Iran and other countries, including Iraq and Lebanon.

In the case of Ukraine too, we had quite a heated debate, because this section of the left blamed the US, NATO and the Ukrainian opposition to the Russian-supported regime for the war that broke out, without seeing it as a war of re-colonisation by Russia. In such cases, there is more likely to be victim-blaming rather than solidarity with the victims.

As Kavita Krishnan argues, their notion of anti-imperialism entails support for a ‘multipolar’ world, where big powers like Russia and China are free to demolish human rights and democracy in their own spheres of interest instead of being bound by these values, which are falsely claimed to be foisted on their own countries and the rest of the world by the Western powers.

As Kavita argues, this denial of universal values – which of course has not been gifted to us by capital or Western imperialism but is being and has been fought for by the working people of the world – is a gift to authoritarian and fascist regimes. It is a form of pseudo-anti-imperialism and selective solidarity, opposing some imperialisms but not others, expressing solidarity with some victims of imperialism but not others.

There’s been a rise in right-wing authoritarianism globally, including in India. Do you think this has shifted the Indian left’s priorities inward, and if so, at what cost to international solidarity?

You’re absolutely right about the rise in right-wing authoritarianism in India and globally, but it hasn’t necessarily shifted the priorities of the Indian left inwards. In the case of Palestine, the U-turn from newly-Independent India, which voted against the partition of Palestine, to the increasingly close relationship between the Israeli state and the current Indian regime has actually dovetailed with an increase in solidarity, because Israel supplying India with surveillance and other military and repressive technologies like Pegasus while government-linked Indian companies invest in Israel in a big way has made it easier to link the struggle against repression in India with the struggle against Israeli settler-colonialism and genocide in Palestine.

But in the case of Ukraine, whole-hearted solidarity with the beleaguered Ukrainian people has been obstructed by the belief of most of the Indian left – including even the CPI(ML)-Liberation – that a multipolar (i.e. multi-imperialist) world would make it easier to fight against fascism in India than a unipolar one, and therefore it would be better not to condemn the Russian aggression and genocide in Ukraine too vehemently.

The crimes of Western imperialism have been so many and so heinous that it’s easy to sweep all other crimes under the carpet, but the correct response should be to demand accountability for those crimes as well as similar crimes by non-Western regimes.

You’ve criticized those who defend Assad as ‘pro-Palestinian’ while ignoring his repression of Palestinians in Syria. How do you respond to people who still frame the Assad regime as part of the struggle against Zionism and U.S. imperialism?

Palestinian blogger Budour Hassan describes the bombing, starvation siege, ISIS occupation while still under siege and total destruction of Yarmouk refugee camp – ‘the capital of the Palestinian diaspora’ – by Assad and his allies, and the emptying of other Palestinian refugee camps too.

There were also thousands of Palestinians incarcerated, tortured and in most cases killed by the regime. This makes a mockery of claims that Assad was pro-Palestinian. It was very notable that so long as Assad was in power, on the one hand he made no moves to reclaim the Golan Heights from Israeli occupation, while on the other hand Israel targeted only Iranian and Hezbollah assets in Syria, leaving Assad’s own forces untouched.

The moment the Assad regime fell, Israel expanded its occupation of Syria in the south of the country, expelling hundreds of Syrians from their homes and shooting anyone who protested. It launched a devastating campaign of aerial bombardment, wiping out the Syrian air force and military capabilities and killing many people too. These airstrikes have continued, using various pretexts.

The message is clear: Assad was no threat to the Israeli state, only after he was overthrown was a threat perceived. You have to shut your eyes to all this if you defend Assad as ‘pro-Palestinian’.

Looking ahead, what would a consistent, democratic, and emancipatory internationalist position look like in relation to struggles in Syria, Iran, and Palestine?

To begin with, it would have to be based on knowledge of what is actually happening currently as well as the history of the struggles, countering the misleading narratives propagated by white supremacists, neo-Stalinists, Zionists, and ethno-religious nationalists of all stripes, which almost universally portray the aggressors as victims and vice versa.

Ways would have to be found to spread this knowledge, encouraging everyone from little children to elderly people to think for themselves rather than accepting uncritically what they are told by leaders. Poetry, art, songs and other creative forms of expression can be used. I was happy to see that Iranian director Jafar Panahi’s film “It Was Just an Accident’ won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes film festival where another Iranian director, Sepideh Farsi, also screened her film ‘Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk’ about the life of Palestinian photojournalist Fatma Hassouna, who couldn’t attend because an Israeli airstrike killed her and nine members of her family after Farsi’s film was accepted at Cannes.

That Sepideh Farsi could combine opposition to the Islamic Republic with a tribute to a Palestinian photojournalist, and that Juliette Binoche, one of the judges, could honour both Panahi and Hassouna, was a moving example of international solidarity.

Action may differ from one situation to another, but in every case there should be insistence on respect for human rights and democracy. In my country, Sri Lanka, Tamils had been oppressed from Independence onwards. My own family had to flee our home when I was a child because my father was Tamil.

But when the Tamil Tigers, the LTTE, started killing Sinhalese and Muslim civilians including children, as well as jailing, torturing and killing Tamil dissidents, when they tore Tamil children away from their mothers to use them as child soldiers, we Tamil socialists protested against them. I also disagreed with their basic goal of an ethnic Tamil state, because it would have been an apartheid state in which non-Tamil minorities had fewer rights or none at all.

In a paradoxical fashion, it would have reinforced the legitimacy of the ethnic Sinhala-Buddhist state we were fighting against by accepting the legitimacy of ethnic and religious states. At the same time, we insist on due process for all those accused of terrorist crimes, with perhaps some allowance being made for those who turn to violence as a consequence of traumas inflicted on them. Non-violent action doesn’t have these ethical problems, although it is always risky in an authoritarian/fascist state.

Of course, the viewpoints of individuals participating in a resistance movement may differ from each other and often do, so it is important for those offering solidarity to listen carefully to all of them. It was extremely disturbing to hear that Syrian refugees were denied the right to speak at left meetings, for example a meeting organized by Stop the War Coalition in the UK, because their view of the Assad regime as intolerably cruel and brutal clashed with the predominant left view that there should be no action against Assad, that perhaps he was even part of the solution in the global war on terror, in this case the Islamic State.

The actual experiences of terror raining down on civilians from Assad’s and Russia’s bombs, dissidents being tortured to death, massive displacement and so on were sought to be silenced because they were inconvenient to the preferred narrative. The same thing has happened to Iranian, Ukrainian and Russian refugees. This is not international solidarity, which should start with listening to the victims and survivors. The result has been the horrific mass graves now being uncovered in Syria, which neither world leaders nor this section of the left took any action to prevent.

Basically, we should uphold values of humanity and the rule of law in every context, without double standards or hypocrisy. International law is not perfect, but it is better than the trashing of international law by the most powerful states that is going on right now. Some socialists see it as not worth defending, but the alternative is the rule of ‘might is right,’ with the powerful, as we have seen, making deals with one another to enable them to crush weaker parties.

You propose pursuing truth as the first step in countering authoritarianism. In an age of disinformation and “alternative facts,” what does that look like in practice, especially for activists and writers in the Global South?

Disinformation and “alternative facts” being circulated at high speed on social media has certainly made it harder to pursue the truth. In India, fact-checkers simply can’t cope with the volume of lies and obfuscations that are pouring out every minute, and even when they have proved something is fake, it has already been shared umpteen times and people continue to believe it. Of course the stories are still full of holes, and if people take the trouble to check them for internal logical consistency as well consistency with their own lived experience, they will be able to detect their untruthfulness. But that takes work which many people are unwilling to do.

I think we have to concentrate on challenging the dominant narratives, which are often shared between left, right and centre. For example, I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard that there was an ‘Islamic revolution’ in Iran in 1979, when there was nothing of the kind. There was a democratic revolution in 1979, and then a struggle between democratic forces and Islamist fascism. As Mansoor Hekmat puts it, 11 February 1979 was a people’s revolution which was only completely crushed by ‘an Islamic, counter-revolutionary coup d’état’ on 20 June 1981.

When you look at it like that, it becomes much harder to legitimize the Islamic Republic even from a liberal point of view much less a socialist one. Then there is the question of the origin of the Israeli state, which is popularly thought to be a result of the Holocaust, when in fact it originated in the settler-colonial, white-supremacist and Jewish-supremacist project of the Zionists back in the 19th century and entailed the destruction of the Palestinians as a people. For Western leaders and most of the media, who have colluded with the genocide in Gaza since 7 October 2023, this perspective is completely lacking.

They have no conception of intersectionality and therefore can’t understand that members of the Jewish community can be oppressed in one relationship while being oppressors in another, so they shut their eyes to the genocide even when Israeli leaders proclaim it loud and clear and soldiers themselves circulate evidence of it.

Anti-Zionist Jews have done a wonderful job making this perspective visible. In these two cases – and many more, including Stalin’s counter-revolution in Russia – once we have succeeded in flipping the script, changing the narrative, disinformation and ‘alternative facts’ lose much of their power.

Hi Siavash:

How might we clarify the ethical content of anti-imperialism?

Why not make it plain.

Colonialism and imperialism openly represses popular and direct self government of ordinary people.

If we are anticolonial and anti imperialist why then aren\’t we explicitly for the direct self government of everyday people?

We cannot critique dictatorship from a republican or nation-state human rights, civil society mentality.

But why is this such a persistent problem? Because these Global South regimes and the left that defends it is hiding behind social identity politics.

But what is the call for recognition really about? Social identity politics. It is the evasion of discussing the actual ethical content of politics and government.

How does this evasion work? By posing the paralyzing question below

Who is the white man to talk about or lecture \’us\’ about merit and responsibility?

Iran, Russia, China and Cuba repeatedly have said related things about the abuse of human rights and economic inequality in the US and Europe.

The point is to rally those behind \’the color curtain\’ toward popular and direct self government.

Otherwise we get into global human rights discussions sponsored by the empire itself.

Apply the same direct democratic and popular self management principles to all countries.

And if your pessimism makes you question if popular and direct self government is possible, consider do the advocates of a nation state and republic really and consistently believe that such associated liberties are possible? Of course not.

Best wishes,

Matthew

I agree with most of this article, but not with the part about Israel. Leaving aside the unholy trio of Netanyahu, Smotrich and Ben Gvir, who are currently leading Israel down a disastrous path, and looking just at the foundation of the state, I want to contest the notion that Israel is a white settler colonialist state: rather, it is the return of an indigenous people repeatedly scattered by waves of imperialist invasion, conquest and persecution, to their land of origin, and the re-establishment of their state. Israel defeated both British and Islamic imperialism to achieve its independence. Let us not forget that the Arab leader in Jerusalem in the 1930s/40s, al Husseini, was an ally of Hitler, who toured a concentration camp, had tea with the Fuehrer, and raised a Muslim SS Battalion.

Yes, Zionism was a 19th century nationalist movement. That is how most of Europe was developing at the time, as old empires began to collapse, and native peoples such as Italians and Germans demanded independence and power in their land of origin, forming new countries. Do we demand the undoing of those nations?

The separatist Arabs who in the 20th century refused citizenship in both the new state of Israel, and in the 70% of Mandate of Palestine territory carved out to form the new Arab state of Jordan, were not in the 19th century culturally “a” people, nor did they have a nationality. They were Ottoman imperial subjects, ruled from Istanbul, living in the large administrative region of Greater Syria. A Palestinian at that time was anyone who lived in that area of Greater Syria and they included Arabs, Kurds, and Greeks. Jews were the majority population in an undivided Jerusalem.

Once large scale Jewish immigration began, Palestine, a neglected backwater, of little interest to the Ottoman Turks or anyone else except the Jews, whose religion and culture have centred on Jerusalem for 3000 years, received for the first time industrial development, and technological improvements in agriculture. Arabs from the surrounding area as well as Jews from Europe immigrated. In the 20th century, when Britain and her allies put an end to the Ottoman empire, Arabs wanted to maintain Greater Syria as one entity, the only change being that it would be under Arab control. There was no question of an independent Palestine: it didn’t have the resources to be self-sustaining and Arabs identified as Arabs, not as a people of Palestinian nationality. Here is what Zuheir Mohsen of the PLO said, as recently as the late 1970s:

In a March 1977 interview with the Dutch newspaper Trouw, Mohsen made the following remark:

“The Palestinian people does not exist … there is no difference between Jordanians, Palestinians, Syrians, and Lebanese. Between Jordanians, Palestinians, Syrians and Lebanese there are no differences. We are all part of one people, the Arab nation […] Just for political reasons we carefully underwrite our Palestinian identity. Because it is of national interest for the Arabs to advocate the existence of Palestinians to balance Zionism. Yes, the existence of a separate Palestinian identity exists only for tactical reasons[…] Once we have acquired all our rights in all of Palestine, we must not delay for a moment the reunification of Jordan and Palestine”.

The currently prevailing understanding of “Palestine “ is a Soviet invention from the late 1960s, when Arafat was told to stop issuing Islamist rants and threatening to annihilate every Jew, & instead re-brand his movement as a national liberation struggle like those in Cuba and Nicaragua, which rightly attracted the sympathy of Western youth.

Everyone knows that in the 1940s, the European Jews immigrating to what became Israel were the remnants of the Jewish communities reduced by the Holocaust to one third of their former size. But what people don’t seem aware of is that Jews were also ethnically cleansed from all the newly created Arab states. More than 800,000 Jews were forced out of their countries, their land, homes, businesses, bank accounts and personal property confiscated. Half of those fleeing the murderous pogroms went to America, the poorer ones sought safety in Israel, which offered them a haven.

Israel’s population is almost 25% Arab. Of the Israeli Jews, the majority are not white, because of the influx of the Mizrahim, the “Arab Jews”. There are also 200,000+ Ethiopian Jews. Yes, thousands of Arabs were displaced as Israel was being formed – and the Turks massacred 1,000,000 Armenians and drove out their Christian Greeks, to form a country of “pure-blooded” Muslim Turks, who now only need to eliminate the Kurds to fulfil their aim – but the world has paid Palestinians ‘ bills for 77 years, and they have refused innumerable peace plans. No help, and no compensation, was ever offered to the Arab Jews.

The world has only one tiny Jewish state, the one place in the world where a Jew cannot be persecuted for being Jewish. There are already 22 Arab countries, which control 99.82% of the Middle East. Are they models of democracy? Is 0.18% of the region too much to allow to the Jews in their land of origin?

I understand people’s concern about the carnage in Gaza. It’s shocking. But look at what the Hamas leaders have said about the necessity of creating civilian casualties so the world will condemn Israel. Ask yourself why women and children have never been allowed to shelter in the safety of the underground tunnels which protect the men, & why Hamas fires rockets from hospitals, mosques, schools and private homes. The Left has it wrong on Israel.

Rohini is partly right but the problem is not confined to the so called left. In India, right wing hates the democratic west for its liberal values. A better way to divide the people is liberal democratic humanists on one side and nationalist, supremacists followers of authoritarian leader whom they see as a savior, (benevolant dectator).