In the pages of ancient manuscripts, beneath the delicate strokes of ink and gold, there is an instrument that appears again and again. Held in the hands of scholars, navigators, and mathematicians, it gleams in the soft candlelight of medieval scriptoria. The astrolabe—an intricate map of the heavens, a device that guided travelers through deserts and oceans, that helped philosophers calculate time and predict the movements of the stars. In the so-called Islamic world, where science and faith once walked hand in hand, the astrolabe was a key to understanding the universe.

Turn the pages of these books, and you will see men—always men—bending over the instrument, measuring the sky, charting celestial paths. Their names are written in history, their contributions celebrated. But what if the hand that refined this device, the mind that advanced its design, belonged not to a man, but to a woman?

Al-ʻIjliyyah (Mariam al-Asturlabiyy) was that woman. A scientist, an inventor, an engineer who crafted astrolabes so precise that they shaped navigation and astronomy for centuries. Yet, history barely whispers her name. She is a shadow, a footnote, erased by the same forces that would later reduce women to the confines of kitchens and homes, that would silence them under the rule of mullahs and clerics.

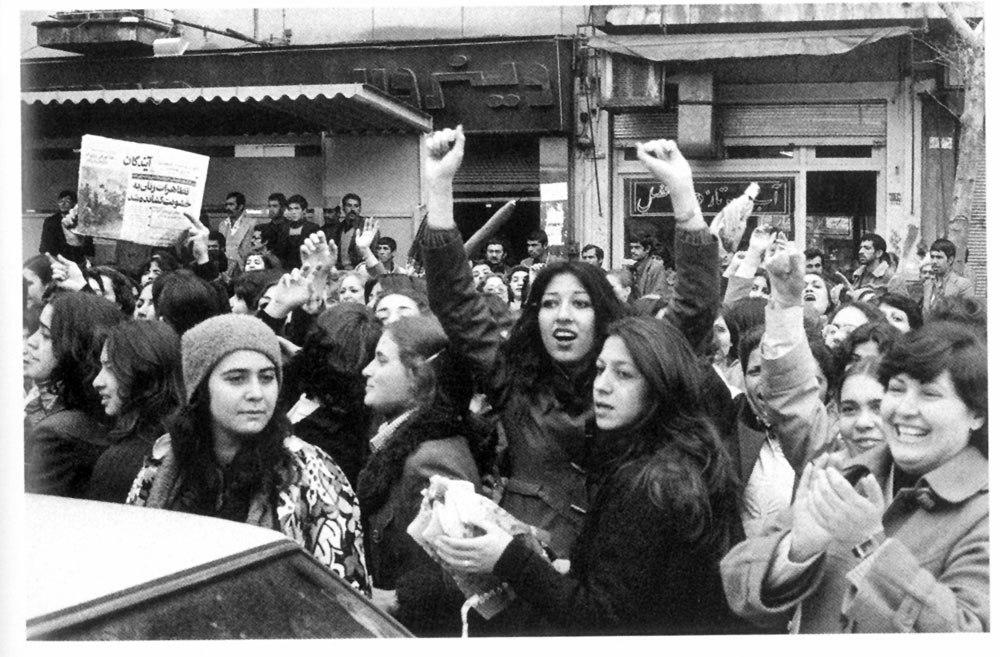

This essay is about that silence—the deliberate removal of women from the history of science and knowledge. It is about the power of religious authorities who twisted faith into a justification for oppression, forcing women into subservience. But it is also about resistance. About the women who fought, who wrote, who refused to disappear, even when their words were censored, their books banned, their voices suppressed. From Iran to Turkey, from Egypt to Iraq, they kept writing, kept challenging, refusing to be erased.

From left: 1) Astrolabe 2) School’s MS Ahmed III 3206 Aristotle teaching, illustration from ‘Kitab Mukhtar al-Hikam wa-Mahasin al-Kilam’ by Al-Mubashir (pen & ink and gouache on paper) located at the Topkapi Palace Museum, Istanbul, Turkey 3) Using an astrolabe for navigation, in Persian manuscript by Iqbâl-nâma Nizâmî, Kâbul or Kandahar, 16th Century

the Erasure of Women in Science

Mariam al-Asturlabiyy was a scientist and craftswoman in the tenth century, working in the court of Sayf al-Dawla, the ruler of Aleppo. She specialized in the construction of astrolabes, complex devices used for navigation, timekeeping, and astronomical calculations. The astrolabe was not just a tool for sailors or astronomers; it was an instrument that connected science with daily life, used in medicine, architecture, and religious observances. By refining its design, Maryam contributed to a long tradition of mathematical and engineering advancements.

Yet, despite her contributions, little is known about her life. Her name surfaces in a few historical records, but there is no extensive documentation of her work, no surviving texts in her own words. This is a pattern repeated throughout history: women who played crucial roles in intellectual and scientific advancements often remain undocumented, their knowledge absorbed into a larger, male-dominated narrative.

Maryam was not the only woman engaged in scientific work at the time. The ninth and tenth centuries saw women active in scholarship, though their visibility depended on social and political circumstances. In Baghdad, the physician and scholar Lubna of Córdoba was known for her work in mathematics and manuscript transcription, serving in the court of the Umayyads in Al-Andalus. Fatima al-Fihri, a century earlier, founded a center of learning in Fez that would later be recognized as one of the oldest universities. There were women poets and intellectuals who participated in literary and philosophical circles, but their names were often preserved only when they had ties to influential men.

As political and religious authorities consolidated their control, opportunities for women in science and scholarship diminished. Access to education became more restricted, and intellectual life was increasingly dominated by male scholars and religious authorities. While early periods of cultural and scientific exchange allowed for some degree of participation, later shifts toward rigid orthodoxy reinforced the idea that a woman’s proper role was within the home.

Mariam al-Asturlabiyys near disappearance from historical memory reflects this shift. Though she contributed to an instrument that shaped navigation, astronomy, and scientific measurement for centuries, her legacy exists only in passing mentions. The absence of detailed records about her work is not a simple accident—it is part of a broader pattern in which women’s intellectual labor was undervalued, dismissed, or attributed to male scholars.

This historical exclusion did not end with Maryam’s time. Women continued to pursue knowledge and contribute to intellectual life, but they faced increasing barriers. In later centuries, religious institutions and conservative interpretations of social roles pushed them further into the margins. Yet despite these restrictions, women persisted in literature, politics, and science. The next section will examine modern women writers from Iran, Turkey, Egypt, and Iraq—women who, like Maryam, had to struggle against the weight of a society that sought to limit their voices.

Restricting Women to Domestic Spaces

Religious authorities have long played a central role in shaping social structures, and in many parts of the Middle East, mullahs and clerics positioned themselves as gatekeepers of morality and social order. With this power came the ability to define women’s roles—not as scholars, poets, or scientists, but as daughters, wives, and mothers, confined to the household. The erasure of figures like Mariam al-Asturlabiyy was not an isolated event but part of a larger effort to push women out of public intellectual life and into domestic servitude.

This was not always the case. In earlier centuries, women participated in scholarly discussions, composed poetry, and, in rare instances, engaged in scientific inquiry. But as clerical institutions gained influence, particularly from the Safavid period onward in Persia and later under the Qajar dynasty, the space for women in intellectual and public life narrowed. The justification was always the same: religious texts were interpreted in ways that emphasized women’s supposed duty to serve their families rather than contribute to society.

In Iran, the consolidation of clerical power in the 19th and 20th centuries further entrenched these restrictions. Even as modernist intellectuals and reformers advocated for expanding women’s education, mullahs resisted, warning that too much learning would corrupt women’s morals and distract them from their “natural” roles. The most radical example of this enforcement came after the 1979 revolution, when the Islamic regime institutionalized these patriarchal restrictions into law. Education remained accessible to women, but always within the limits set by religious authorities. Women could become teachers or doctors, but never decision-makers. Their presence in public life was tolerated only if it served the state’s ideological goals.

The same pattern emerged in other countries where religious conservatism gained political influence. In Turkey, the late Ottoman period saw debates between secular reformers and Islamic scholars over the role of women in society, with clerics arguing that Western-style education would erode traditional values. In Egypt, the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood and similar movements promoted the idea that women’s liberation was a colonial agenda meant to destroy Islamic culture. In Iraq, the Ba’athist state alternated between promoting women’s labor for economic reasons and restricting their freedoms when political alliances with religious groups required it.

At the core of this system was the idea that a woman’s primary duty was to serve her family, particularly her husband. The household became both a physical and ideological prison, reinforced by law and custom. Even when women worked or studied, their success was always measured by how well they fulfilled their domestic roles. A woman could be a doctor, but she still had to be a perfect wife. A woman could be a writer, but her work had to align with moral expectations.

This ongoing tension—between women’s intellectual and social ambitions and the restrictions imposed by religious and political authorities—defines much of the modern struggle for women’s rights in the region. Women who stepped beyond these boundaries, who wrote, who challenged authority, were met with repression, censorship, and exile. The next section will explore some of these women—writers from Iran, Turkey, Egypt, and Iraq—who, like Mariam al-Asturlabiyy, refused to accept the space that society assigned them.

Resistance Against Patriarchal Norms

The history of women’s intellectual contributions in the Middle East is marked by both achievement and suppression. From literature to science, women have fought for recognition, often in societies that sought to limit their voices. Many have faced censorship, imprisonment, or exile simply for writing or conducting research that challenged established norms.

For women writers in these countries, censorship is not always direct. Sometimes, it comes in the form of social pressure, in the quiet threats that discourage women from speaking too openly. Other times, it is brutally explicit—books are banned, writers are arrested, and exile becomes the only option. The pattern is clear: as soon as a woman’s voice grows too strong, too critical, too independent, there is a push to silence her.

Yet, despite these challenges, women continue to write. They continue to challenge the structures that try to confine them, just as Mariam al-Asturlabiyy once worked in a field where women were not supposed to exist. The next section will examine the tactics used to suppress these voices—through censorship, imprisonment, and political persecution—showing how religious and political institutions work together to keep women from claiming their space in the public sphere.

- Assia Djebar (Algeria) – Novelist and filmmaker who wrote about the historical erasure of women in the Arab world. Her works were often censored for their feminist and anti-colonial themes.

- Dunya Mikhail (Iraq) – Poet and journalist who documented war, exile, and the oppression of women under dictatorship and religious extremism.

- Elif Shafak (Turkey) – Novelist known for tackling gender, sexuality, and historical taboos. Faced legal charges for “insulting Turkish identity.”

- Fatima al-Fihri (Tunisia/Morocco) – Founded the world’s oldest existing university in Fez in the 9th century, yet her contributions are often overshadowed by male scholars.

- Forough Farrokhzad (Iran) – Poet who challenged gender norms, sexuality, and the oppression of women in deeply patriarchal Iranian society.

- Halide Edib Adıvar (Turkey) – Early 20th-century novelist and nationalist who advocated for women’s rights and modern education.

- Huda Sha’arawi (Egypt) – Writer and political activist who helped establish the Egyptian feminist movement in the early 20th century.

- Leila Ahmed (Egypt) – Scholar of Islam and gender, her work Women and Gender in Islam remains a landmark critique of the way religion has been used to justify women’s subjugation.

- Leila Abouzeid (Morocco) – The first Moroccan woman to have her work translated into English, addressing issues of gender and colonial legacy.

- Liana Badr (Palestine) – Novelist and journalist who writes about the effects of war and exile on Palestinian women.

- Al-ʻIjliyyah (10th-century Aleppo) – Engineer who refined the astrolabe, an essential tool for navigation and astronomy. Her contributions were largely erased from history.

- Maryam Mirzakhani (Iran) – Mathematician and the first woman to win the Fields Medal, the most prestigious award in mathematics. Despite this, Iranian law did not allow her to pass citizenship to her daughter because she was a woman. The law was only changed after her death.

- Mona Eltahawy (Egypt) – Journalist and feminist activist who has written extensively about women’s rights in the Middle East, often facing censorship and backlash.

- Nawal El Saadawi (Egypt) – Medical doctor and writer who exposed gender violence, female genital mutilation, and the oppression of women under religious laws. Imprisoned for her activism.

- Naziha al-Dulaimi (Iraq) – First female cabinet minister in Iraq and a leading advocate for women’s legal rights in the mid-20th century.

- Radwa Ashour (Egypt) – Novelist and scholar who wrote about colonialism, resistance, and the role of women in revolutionary movements.

- Raja Alem (Saudi Arabia) – Novelist whose work challenges gender restrictions and censorship in Saudi Arabia.

- Simin Behbahani (Iran) – Poet known as the “Lioness of Iran,” who used her poetry to critique dictatorship, censorship, and women’s oppression.

- Shahrnush Parsipur (Iran) – Novelist who was imprisoned for writing Women Without Men, which challenged traditional gender roles and religious authority.

Between the years 2001 to 2010, the Annual Lasting Figures Conference was held in Iran. The goal of this conference was to introduce prominent figures in various fields of science and culture in Iran. Over a decade of its existence, 206 men were selected, while the number of women was only 9!

Many of these women were forced into exile, imprisoned, or had their works banned. Yet, despite the immense barriers, they continued to write, publish, and contribute to knowledge in ways that shaped their societies.

The case of Maryam Mirzakhani is particularly telling. Despite winning the highest honor in mathematics, her status as an Iranian woman still placed her at a legal disadvantage. Under Iranian law, only men could pass citizenship to their children. As a result, even after her global recognition, Mirzakhani’s daughter was not eligible for Iranian citizenship. This law was finally changed in 2019—years after her death. Her case is a stark example of how the legal system, deeply influenced by religious and patriarchal structures, systematically excluded women from full citizenship rights.

These writers and scientists are part of a long lineage of women who resisted the forces trying to confine them to the domestic sphere. Their struggles mirror those of Mariam al-Asṭurlābiyya centuries ago, reminding us that the erasure of women from history is not passive forgetting but an active political and ideological choice.

Censorship and Repression of Women Intellectuals

Women who write, who challenge, who ask questions—these women have always been seen as dangerous. In societies where religious and political authorities control public discourse, a woman’s voice is not just unwelcome; it is a direct threat. The history of censorship against women intellectuals in the Middle East is not just about banning books or silencing individual authors. It is about the systematic effort to erase women from the public sphere, to make their knowledge, their creativity, their resistance invisible.

Governments and religious institutions have worked together to limit women’s access to publishing, education, and media. Laws regulating morality, blasphemy, and public decency have been used as tools to silence female intellectuals. In Iran, after the 1979 revolution, literature was subject to intense scrutiny by the Islamic regime. Books by women that challenged gender roles, such as Shahrnush Parsipur’s Women Without Men, were banned, and Parsipur herself was imprisoned. The same fate awaited many others who dared to write about female sexuality, political repression, or religious hypocrisy.

In Saudi Arabia, censorship operates through strict pre-publication controls, forcing writers to submit their work for approval before it can be printed. Women who write about gender oppression, such as Raja Alem, have had to navigate a landscape where even indirect criticism can lead to bans or forced exile.

Egyptian authorities have long used religion as a justification for censorship. Nawal El Saadawi, one of the most vocal feminist writers of the 20th century, was imprisoned for her work on women’s rights and later lived in exile due to threats from both the government and Islamist groups. Her books, which exposed the brutality of female genital mutilation and patriarchal violence, were banned for decades.

In Iraq, under both Saddam Hussein’s rule and later Islamist influences, women writers faced the dual pressure of state surveillance and societal backlash. Poet and journalist Dunya Mikhail had to flee Iraq after receiving threats for her work documenting war crimes and violence against women.

Beyond imprisonment and exile, one of the most effective tools of repression has been book bans. In Turkey, Elif Shafak faced charges of “insulting Turkishness” due to the political themes in her novels. In Iran, Simin Behbahani’s poetry was censored for containing veiled criticisms of the regime.

For many women, the constant threat of censorship leads to self-censorship. Writers learn what they can and cannot say, what subjects will get their books removed from stores, what ideas will bring them under government surveillance. This silent repression is just as powerful as an official ban. It forces women to navigate a maze of restrictions, shaping their work not according to their own thoughts but according to the limits imposed upon them.

For some, writing becomes impossible under these conditions, and exile is the only option. Many of the Middle East’s most influential women writers and intellectuals have been forced to leave their countries in order to continue their work. Nawal El Saadawi, Dunya Mikhail, and others had to choose between silence and exile. Maryam Mirzakhani, though not a writer, left Iran to pursue her mathematical career in the United States, where she eventually won the Fields Medal. Even in exile, the impact of censorship follows them—many cannot return to their homelands, and their books remain banned there.

In many cases, censorship is not only enforced by the state but also by Islamist movements that view women’s intellectual contributions as a form of rebellion against religious and social order. In countries like Egypt, Iraq, and Afghanistan, Islamist militias have threatened, attacked, or even assassinated female journalists, teachers, and writers. The fear of violence forces many women into silence long before the state needs to act.

Despite these obstacles, women continue to write. They publish underground, they circulate their work online, they move abroad and find new ways to speak. The censorship imposed on them is not just about silencing individuals—it is about controlling historical memory, about making sure that future generations do not have access to the knowledge these women produce.

The story of Mariam al-Asṭurlābiyya, erased from history despite her contributions to science, is not just a relic of the past. It is a pattern repeated over and over. Women’s voices are made invisible, their work attributed to men, their books banned, their words seen as too dangerous to be allowed. But the resistance continues. Women refuse to be erased, and their voices, no matter how many barriers are placed before them, continue to find ways to be heard.

Against Patriarchy, Authoritarianism, and Orientalism

The erasure of Mariam al-Asṭurlābiyya and countless other women from historical memory is not just the result of local patriarchal structures but also of the way knowledge itself has been shaped by colonial and Orientalist narratives. The West has long presented women in Middle Eastern societies as passive victims, reinforcing the idea that their oppression is inherent to their culture rather than the result of political, religious, and social forces. This framing serves a dual purpose: it justifies foreign intervention under the guise of liberation while obscuring the reality that women across the world—whether in Iran or the United States, Egypt or France, Saudi Arabia or Brazil—face different forms of patriarchal oppression.

At the same time, within Middle Eastern societies, religious and political authorities have worked together to maintain strict gender hierarchies. Authoritarian regimes and clerics have used religion to justify control over women’s lives, restricting their access to education, employment, and political power. This is not unique to any one country. In Iran, mullahs have shaped laws that deny women full citizenship rights, as seen in the case of Maryam Mirzakhani, who, despite winning the highest honor in mathematics, was unable to pass her nationality to her daughter. In Saudi Arabia, women’s mobility and legal autonomy were historically restricted under religious law, only changing when it became politically convenient for the ruling monarchy. In Egypt, Turkey, and Iraq, women’s rights have expanded and contracted depending on the balance of power between secular and religious forces, with neither fully committed to women’s liberation.

Yet, the struggle of women in the Middle East cannot be viewed in isolation. Women in Rojava have built a system of self-governance that challenges both state authority and patriarchal oppression. Women around the world have fought against the structures that seek to silence them. In East Asia, feminist movements have challenged deeply entrenched Confucian traditions that subordinate women to the family unit. In South Korea and China, women have pushed back against forced labor, gender-based violence, and economic inequality. In Africa, women have led movements against colonial legacies that reinforced patriarchal power structures, fighting for land rights, political representation, and bodily autonomy. In South America, where dictatorship and neoliberalism have combined to exploit women as workers and silence them as political actors, feminist movements have risen in defiance. The Zapatista women in Chiapas have fought for autonomy, land, and dignity against both the Mexican state and capitalist exploitation. From the Ni Una Menos movement in Argentina, demanding an end to femicide, to Indigenous women in Brazil defending their land against capitalist extraction, the fight for gender justice is global.

The international struggle against patriarchy, authoritarianism, and economic exploitation reveals a common truth: women’s oppression is not the result of a single religion, culture, or ideology. It is a system upheld by those in power—whether through religious justification, legal restriction, or economic control. Orientalist narratives that depict Middle Eastern women as uniquely oppressed serve only to obscure this reality, preventing solidarity between women’s movements across the world. The goal of such narratives is not to help women but to divide them, to present their struggles as separate rather than interconnected.

Despite the weight of history, women continue to resist. Writers like Forough Farrokhzad, Nawal El Saadawi, and Elif Shafak have fought against both local censorship and global stereotypes. Women scientists like Maryam Mirzakhani have broken through structures designed to keep them invisible. The attempt to erase women’s contributions—whether in literature, science, or politics—is not unique to any one place, but neither is the refusal to be erased.

Mariam al-Asṭurlābiyya’s near disappearance from history is not just a story of a forgotten scientist; it is part of a broader pattern of silencing women’s knowledge, whether by religious elites, authoritarian regimes, or the colonial narratives that decide whose history is worth remembering. The struggle to reclaim these voices is ongoing, and every woman who speaks, writes, organizes, or resists carries forward the work of those who came before her—not just in the Middle East, but everywhere.

Religion isn’t ‘twisted’ against women. With regards to the three monotheisms, it is by its nature, and in its foundational texts, intrinsically anti-women.

The Quran contains diverse and contradictory content. For example, one of its teachings is patience and forgiveness, and it also has important recommendations for addressing poverty. But who actually follows them? This is where selectively emphasizing certain aspects of religious commandments becomes a tool of oppression. Throughout history, religions have been interpreted and practiced in various ways.