In the tent, feverish from the heat, we vowed never to forget each other until the end of time; me, Tayebeh, Ismail, Faisal, and his sister, Forouzan. It was the eighth day of our journey. Forouzan was leaning against the tent pole, laughing at this scene. The kids had talked about war, life, and being refugees; and we had listened. Inside the tent, beside the bookshelves, there was an empty tea flask and a sugar bowl. Faisal stood up, picked up the sugar bowl, and held it in front of each of our faces. “Eat a piece of sugar so we never forget each other.” It tasted like dirt.

Narges Joodaki was born in 1975 and writes in the social domain. She started reporting in 2001 and her first experiences were with the Bam earthquake and the Golestan flood. She is a well-known reporter and won the award for the best report at the twentieth Press Festival in 2013. She has worked as a journalist for newspapers such as Jahan-e Sanat, Farhikhtegan, Tehran Today, Etemad, and Sarmayeh, and has been the social editor for the Arman and Shahrwand newspapers. She also served as the editor-in-chief of the Shahrwand newspaper for a year and has been the social editor of the monthly magazine Shabake-ye Aftab from 2012 to the present. Her writing is characterized by its clean prose, deep perspective, contemplation on subjects, and sincerity. This report is taken from Shabake-ye Aftab magazine, (Issue 57, September 2021).

The Surge of Displacement

Amidst the dust and darkness, nothing is clear; just as we don’t know what awaits us in the deserts of Afghanistan. We’ve been told there will be no phones, and our contact with the outside world will be cut off. Me and a few other instructors from the Children and Adolescents Intellectual Development Center are going to spend ten to twelve days playing and painting with children displaced by war. They have been living in a camp since Mehr month, and it’s unclear what their fate will be after this war. It’s night. Twenty years ago. Nowruz 1381. We’re heading to the east of Zabul, and the sun, tired, dips into the west. At the border checkpoint, our car is stopped several times for questioning. The car and the road swing in the darkness. This point is where our Sistan connects to their Nimroz province. We stare at the road. The wind constantly picks up handfuls of dirt from the road and slams it against the window. We don’t know which day of Sistan’s 120-day winds it is.

We’re seventy kilometers away from Zabul, heading towards Nimroz. With every gust of wind, our conversation is cut short, and everyone falls silent for a few moments. The Zabuli instructors and the driver talk about the ruins of “Dahaneh-ye Ghoulaman” and the ancient capital of Sistan. Another eight or nine kilometers deeper into the darkness, and we’ll reach the camp. Two cars flash their lights. We stop. They stop. They ask the driver why he turned around. The driver says he lost the road in the sandstorm. They leave. We proceed.

The camp’s electric lights are visible through the dust and glass. When Afghan refugees fled the American bombardment towards the Iranian border, the Red Crescent and international organizations stopped them at two camps, Mil 46 and Makaki, until the war’s outcome became clear. Six months have passed, and the war continues.

In September 2001, Al-Qaeda carried out several suicide attacks on the World Trade Towers and the Pentagon. 3,000 people died. News networks were filled with explosions. Television showed an image of several people who had fallen from the towers, suspended between the earth and the sky. It was said these deaths were connected to the Taliban and Afghanistan. After the Taliban took control of Afghanistan, Al-Qaeda built itself under the Taliban’s shadow, trained its forces militarily, and then attacked the United States, thousands of kilometers away. It was a complex operation. None of the attackers were Afghan, but after the September 11 explosions, the United States felt no need for United Nations Security Council permission to attack Afghanistan, and continuous bombardment began.

In the fall and winter of 1380 (2001-2002), Iranian televisions showed images of the displaced people in camps Mil 46 and Makaki, with the voice of Dawood Sarkhosh, an Afghan singer, singing about a “land tired of injustice.”

Now, spring has arrived and passed the borders. Refugees from Kabul, Kandahar, Baghlan, Panjshir, Kunduz, and Herat have somewhat adapted to camp life. Women line up their plastic jugs in the endless queue for drinking water in the morning. Men sit in the shade of the tents, chatting, and the children, who are numerous and everywhere.

Give me a pen to write

Through the gap between the two entrance curtains of the tent, I see the legs of a mujahid man coming towards us. He has a gun in his left hand. As he approaches, he raises his voice. We all go outside. He is angry. He asks why his child has not been given a certificate. He is referring to a library membership card. Our answers do not satisfy him. Answers and questions become intertwined, and the voices get louder. He cannot believe that this library card cannot replace any academic qualification and is of no benefit to his son’s future. Afghans have longed for a piece of resettlement card, passport, ID, or work permit during years of migration and displacement. The issue is resolved with a promise that “new documents will arrive from Zabul in a day or two.”

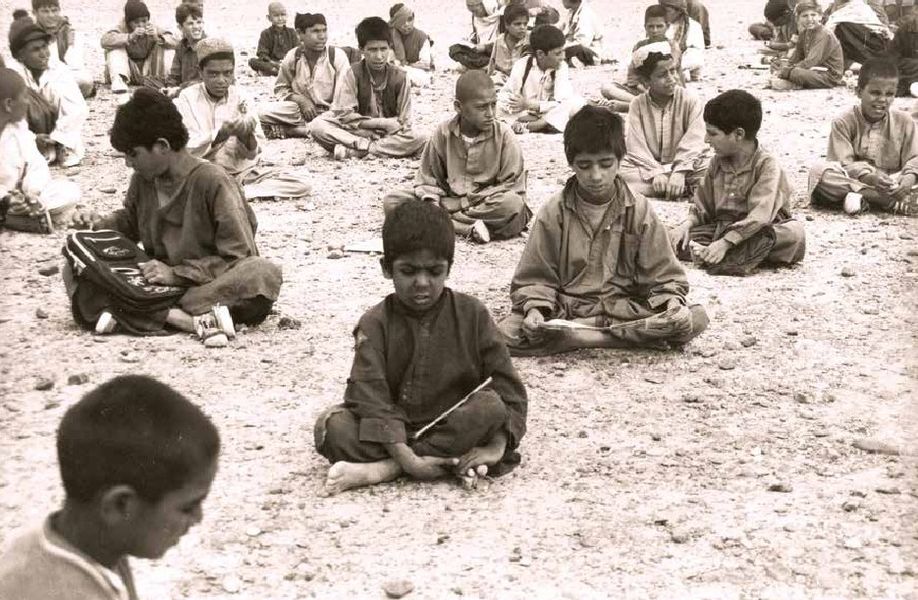

The center’s tents are opposite the mujahideen’s tent. Children, boys and girls, young and old, sit in the tents. In the expanse of the Nimroz desert, there is no shade of trees or buildings. Everything is laid bare under the sun.

The hot air inside the tent mixes with the sour and sharp smells of stale sweat. Among the dusty clothes and hair, the eyes of the children shine. The children draw pictures. They draw so much that the pencils and papers run out. Library cards run out. A thousand times a day they say, “Mr. Teacher, give me a pen to write.” Faisal says, “They have never had a female teacher before. I have seen female teachers in Pakistan before.” In the following days, they learn to call us “Teacher Sahib” or by our first names.

The Afghan teachers at the camp are all men. One of them always wears a red hat and has a pen in his shirt pocket. A large rainbow swirls in the bowl of his large eyes. He is always tired. He always scratches his forearms and legs. He speaks staring into the distance. His gaze travels to the horizon and back. He talks less about himself and more about Iran. He says this war will not end anytime soon. He is a good predictor. At least 15,000 national security forces and 20,000 civilians will be killed over the next thirteen years.

Another teacher, who is the oldest among them, fought in the ranks of the mujahideen before becoming a teacher, and is also a poet. He wears Afghan trousers and a shirt, and ties a white turban. Faisal’s father, who was a fighter, is also fond of poetry. He says Afghans marry a lot, but I say one God, one wife. And he recites a poem about love. Faisal says his father was a logistics agent in the Soviet. They are from Kabul. He remembers their house had everything in abundance. They had a bed brought from the Soviet that was worth 300,000 Tomans. He says my father brought us clothes that no one in Kabul had. But when the war started… .

Why did the war happen?

Faisal explains to me: “The war happened because, let’s say, I am the president. I am sitting here. I want to command everyone. Everyone wants to oppress the people. But our people want to go to school and live their lives.”

Someone should one day calculate and write down the total number of casualties from Afghanistan’s continuous wars; the number of displaced people; the figures of the vast number of wounded before and after the wars with the Soviet Union, Britain, the Taliban, and the United States. Traveling on the Silk Road could have been as smooth as a dream. But Afghanistan, located at the crossroads of Central Asia, East Asia, and West Asia, has always been like a furnace. Either war or coup. After the Soviet war in Afghanistan, 1 million corpses were left on the ground, and 5 million people became refugees. That is why Abbas Hejrani, Faisal’s father, named one of his ten children Hijrat (Migration), one Sangar (Trench), and one Paykar (Struggle).

Fluid wave

In the boys’ paintings, airplanes drop bombs on people. The girls’ drawings are filled with flowers and vases.

On the back of the drawing sheets, fathers write letters; poems describing their homeland. Abdul Sattar’s father has drawn a green mosque and placed a fish above its dome. On the back of the paper, he writes: “Twenty years of war upon us, we all became refugees. Migrants and homeless, we all became wretched. We are all thankful to the people of Iran. Homeland! Your tall mountains all hold joy, your intoxicated sea has a fluid wave.” He writes and writes until the paper turns black. The children in the drawing class draw and color until the colored pencils become so small they no longer fit in their fingers. They draw and recite loudly in response to the teachers. “Brown is like mountains and rocks, black is pretty for hair.” There are not enough new pencils for all the children. On Faisal’s suggestion, we cut the pencils in half.

Everyone goes to the communal prayer after the morning class. The children are in Quran class until three o’clock and then return to the workshop and library until the evening when it gets dark, and the camp prepares for sleep.

Sometimes, the men gather in front of our tent to watch TV. The TV is placed outside the tent on a small stand. They follow the series “Red Line” on Wednesdays. One night, the movie “The Fairy” is also broadcasted. Niki Karimi constantly prays, fasts, and lashes out at others. Every time she shouts, the men’s laughter breaks the night’s silence in the camp.

The mothers do not bother with us unless we ourselves peek into their tents. However, the male instructors maintain a distance from the women of the camp. They say a few weeks ago, one of the Red Crescent workers took a child’s doll to the edge of a tent and handed it to her mother but got slapped by the woman’s husband. The atmosphere in the camp is fragile.

Faisal says his friend, Abbas, works with the Red Crescent kids, but a few days ago, the mujahideen complained about the lack of food and told Abbas not to work in the Red Crescent tent anymore. Faisal says Abbas loves his job and is upset about what happened. Trust among the residents is shaky. But as time piles on time, friendships grow stronger. Mr. Rahimi, a mobile instructor from the foundation, came with his wife, daughter, and son from Kurdistan. He says his family was worried about him coming on the mission alone; so, with insistence, he convinced his supervisor to let him bring his family along. The presence of Mr. Rahimi’s family is reassuring.

One day, Abbas also comes in front of our tent with his mother, sister, and brothers and gives us a letter to deliver to his daughter in Kheyrabad, Varamin. They stand in front of the tents so I can take a family photo to send to their daughter. They squint their almond-shaped eyes in the sunlight.

Bitter, like a ‘tool’

Among the kids in the class, there’s a girl who seems to have a face made of stone. She looks on bitterly. Most of the time, she hooks her hands together and sits in a corner, watching the kids play in the tent. She doesn’t answer any questions. She doesn’t join in any poems group. She doesn’t touch any pencils. Esmaeil says she is “shy.” However, Faysal knows the pain the girl is experiencing. He says she has to go to her husband’s house in a few months. She is nine years old, her name is “Wasila.” They have told her that her husband, “Qurban,” will come soon, and then she must stay in the tent with the women.

The sorrow in her eyes does not let us forget the war and displacement in the children’s laughter. “Wasila’s” presence makes the air in the tent feel heavier. It suffocates us. We give “Wasila” a book to take to her tent and pencils and paper for drawing. “Wasila” wears a faded navy-blue shawl and a long gray dress. She is thin. She has a mole beside her thin lips. We make it a point to have the kids go after “Wasila” every day and bring her.

I ask the kids to read poems other than what we have read in the book. Seven-year-old Sayyid Taghi reads: “The oppressor has stopped me on my way, He has hidden my belt away. My belt was made of solid gold, Its emblem, remember, was a sign of God.”

After class, Faysal comes to the tent with a woman. The woman hesitates, so Faysal explains on her behalf that she has come for her daughter, who cannot come to class, to take a book. We accompany the woman. About ten to fifteen women and children also follow us to the tent. The girl is sitting next to a pile of bedding and a few bowls and plates. Her lips are parted. She smiles with difficulty. “Shakiba” was traumatized during an American plane bombardment in Kabul. Her head was injured, and since that day, she has had difficulty speaking and “avoids everyone.”

On the way back, I talk with Esmaeil and Faysal. Faysal says he wants to study and become a doctor. He wants his daughter to study and become an engineer or a doctor. “Because the Taliban deprived girls of education, and we forgot about them.”

Faysal learned the alphabet in a school in Kabul. A few years later, his father, fearing the Taliban, sent him to Quetta, Pakistan, to his uncle’s. He stayed away from his family for six years.

“Have you seen the Taliban?”

He says: My mother had told me that I was young and the Taliban would not bother me. One day, I went to the city with my uncle. I stood in front of a tape store. At that moment, a Taliban vehicle arrived. A Taliban got out and said, “Hey boy, come here.” He grabbed my hair in his hand. He threw me into the vehicle and took me away. No matter how much I said to wait and talk to my uncle, he refused. With scissors, he cut my hair. He asked, “Where does this road go?” I said, “Kabul.” He asked, “Where are you from?” I said, “Pakistan.” He asked, “Where are you going?” I said, “Jalalabad.” He said, “Take this,” and slapped me in the face. My eye was blind for several days. When I returned to school, my classmates laughed, and I was very upset. The girls laughed too.

Faysal says Pakistan is a good country. There, he learned Urdu and English, and now, when he goes to the Doctors Without Borders tent, he can easily talk with everyone.

Faysal and Esmaeil met in this camp. Esmaeil is nine years old and from Bamyan. He only remembers the bombings in Bamyan and the trees around their house that turned green in spring. He says, “We had a farm, and in spring, we would sleep in the mountains. In the morning, we would come down from the mountain, go to school, and after school, we would go back to the mountain.”

He wants to become a pilot. “To bomb America. It doesn’t matter what happens after that because they killed our people.” Esmaeil plans to name his daughter Krishna and send her to school in the future.

Escape from War

The first morning in the camp had a strange picture. Tayebeh and I come out of our container residence. It’s just a few steps away from the Red Crescent tent and the center. The sun rises from the east. Many men and women from the camp scatter around. Their shadows stretch on the ground. Men’s turbans flutter in the morning breeze.

I ask where they are going.

A colleague from the center smiles and says, “To relieve themselves.”

The Red Crescent has built 20 field showers and 116 toilets. There are 6,000 people living here. Some of them avoid using the toilets. In the following days, some men laugh when they see us with a water jug. During our ten days stay, we only use the shower twice. Each shower container has several showers but no proper locks. The bathroom door opens to the thick darkness of the night desert. Someone stands guard near the bathroom so someone can take a quick shower. Stars are visible above the iron door’s half.

Women in the camp bathe in the tents, and children are bathed in a basin with a few bowls of water, next to the tent. Wind and dust do not cease in the camp.

In the middle of the night, suddenly the sound of a storm scares the sleep out of the camp. Nothing can be seen outside the container. The wind is so strong that we fear the cubicle might fall apart and the wind might carry us away. We wake up and, before anything else, put on our outdoor clothes and tightly tie our scarves.

The sound of people’s murmuring mixed with the howling wind. We go back to sleep after an hour in the same clothes.

In the morning, the camp is still there but disordered and chaotic. The wind has uprooted and taken away two tents. Several other tents have fallen. Men are securing the tent poles again. All the children, except for Esmaeil and Faysal, say they were scared last night.

The children make kites out of paper, string, and plastic. They play with the wind, and the sky of the camp fills with paper kites. One or two kites get stuck on the electric poles.

One of the children, who has scars on his face, holds my hands and stares at the sky. The Red Crescent has advised us to regularly wash our hands to avoid getting sick. After the storm, I have a cold sore on my lips. In a hurry, I go to get soap from the container, twist my ankle, and hit my face on the door frame, injuring my face.

I go to the Doctors Without Borders clinic. It’s crowded. Someone has put his wife in a wheelbarrow and is taking her inside the medical tent. The nurse says today is actually our quiet day. High blood pressure in one person, kidney disease in two people, stomach ulcers in six people, sore throat in seven, colds in twelve, diarrhea in twenty-five, bloody diarrhea in twelve, malnutrition in three, back pain in thirteen, earache in six, toothache in four, and other diseases in thirteen people. The camp has one ambulance, nine paramedics, and two doctors.

Outside the field clinic, a boy sits on the ground next to his father, his arms and legs in casts. His father says he stepped on a mine while playing and was injured. They fled from the war, but the war doesn’t leave them. A few days ago, several people from international organizations came to the classes and explained to the children not to touch if they saw mines. They had brought a few types of mines as examples. They also gave out brochures.

Faysal says a man had a stomachache last night and went to the city of Zaranj in a car looking for herbal medicine. The cost of going to Zaranj is 35,000 tomans. He says if you want, we can go see Zaranj one day. The center’s instructors say it’s not advisable to leave the camp. Those who went to Zaranj for shopping have brought us sweets from there.

No Consolation

On Sizdah Bedar, we take the children a hundred meters away from the camp, fearing to go further. Everyone sits in several concentric circles. Mr. Rahimi and another instructor from Kermanshah play the drum. Mrs. Rahimi and her son dance Kurdish. The ice breaks among the Afghan instructors. The children clap. The instructor with the red hat dances. Mr. Hakimzadeh says, “Can you believe I am dancing after 23 years?” Faysal’s father says, “We have lost hope in fate. It’s good enough that hope is instilled in the children’s hearts. Our fate was not decided by pen and book; it was determined by guns. I can’t believe they will become teachers one day. We only imagine being commandos.” Abbas Hejrani, the one who usually smiles the most, neither dances nor smiles. He says if we had unity, we wouldn’t be refugees.

Every day, new families join the camp. Most are women and children with a bundle of their lives that they have rescued from danger.

After the American attack and coalition forces, the Taliban retreats, and Al-Qaeda flees to Pakistan. Representatives of Afghanistan’s political and military groups agree in the Petersberg Hotel in Bonn, Germany, to establish a provisional government. Hamid Karzai becomes the head of the interim administration.

The Americans’ “Operation Enduring Freedom” lasts thirteen years, and throughout these years, the displacement continues. Migrants, both legal and illegal, come to Iran in groups, and voluntary return plans do not satisfy them to return to their bloodstained memories. During these escapes, many women buried their dead children by the border and moved on. Many men burned in smugglers’ vehicles. The director of a self-run school in Tehran said children convulse from the terror of war.

Camp Mile 46 and Maakaki camp were dismantled in May 2002, eight months after their establishment. The 12,000 refugees from these two camps each went their own way towards their destinies.

Before our return from that journey, the veteran instructors had told us to be careful not to let the children become too attached to us and to leave the tent without saying goodbye on the last day and get into the car. When the back door of the jeep closed, our throats tightened with emotion.

The earthy taste of the sugar that dissolved in our mouths that day will never be forgotten. We never saw Faysal, Esmaeil, the other children, or the teachers again. All we took from there was a letter from Abbas, a bunch of fabric dolls, some drawings, and a few polished white stones that “Wasila” brought me on the last day. The deserts of Nimroz were full of those stones, which were traded in the last days. Whenever we asked “Wasila” to tell a story, she only said one sentence and then silence: “There was, there was not, apart from God, no consoler.”

Afghanistan saw some peace after the establishment of the central government. However, explosions and killings never completely ceased. The Americans and their allies were still there. In 2009, when I went to Herat to participate in the international conference on “Media and Elections” with the Association of Iranian Journalists, the city seemed prosperous and free, but on the very first day, a bomb exploded near our hotel. Journalists from other countries immediately sought refuge in their embassies and did not participate in the program anymore. However, Iranians and Afghans proceeded as planned. There were extensive discussions, a visit to the Tomb of Pir Herat, listening to Rabab by Rahim Shahnavaz, and a world of hospitality.

Now, twenty years have passed since the presence of the Americans and coalition forces. The Americans announced they were leaving Afghanistan and leaving Afghans to their own devices, saying the resurgence of the Taliban is not their concern. Before leaving, they negotiated with the Taliban.

The United States chose September 11th for the departure of its last military group. While no one has yet asked, “What peace was this two decades of war meant to achieve?” In these twenty years, $2 trillion was spent to result in 240,000 deaths, including 120,000 civilians, men, women, and children.

In recent years, the number of terror attacks has increased. Several journalists and singers have been killed. On November 2nd last year, Kabul University was attacked, and on May 8th, 2021, Sayed Ul-Shuhada High School in Kabul was drenched in blood.

Since 2020, more bombs have exploded in Afghanistan than anywhere else in the world. The Taliban and Al-Qaeda are still present, and ISIS has added to global fears. The future of Afghanistan is murky and terrifying. The Taliban have returned stronger and taken over the country. People cannot believe that, despite the vast amounts of money spent on the army, it could not resist the Taliban. They say the government’s corruption has ultimately harmed the people and themselves. Farzad, a journalist who spent fifteen days on the front lines of war and siege, writes to me: “We are in pain. What can be done? But to summarize, we were sold out.”

In the first three months of 2021, civilian casualties increased by 29%, making Afghanistan the deadliest country for children. Following the conquest of provinces, thousands of refugees fled south towards Kabul. Thousands more rushed to Milak at the Nimroz border. Back to square one. But the world situation has dramatically changed from twenty years ago. Walls have been erected against migrants at the Turkey-Greece border. The world is sick, and everyone is engulfed in their own misery. Men talk about peace with the Taliban, but Salima, a governor of one of the districts in Balkh, takes up arms and fights until she is captured, perhaps because she knows, as Afghan journalist Galalai Habib says, women and children are the true victims of wars.

Support The Fire Next Time

I started this space with a simple but urgent goal: to speak freely and honestly about Iran—beyond the headlines, beyond the usual narratives. Inspired by James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, this blog is a place for difficult conversations, for challenging power, and for amplifying the struggles of those who are too often silenced.

Independent writing like this doesn’t have corporate backing or institutional support—it exists because of readers like you. If you believe in the importance of a space that pushes back against repression, that refuses to look away, and that insists on telling the truth, I invite you to support this work.

You can help sustain my work by becoming a member on Patreon:

Click here and choose an option

Your support not only helps keep this space alive but also ensures that these critical discussions remain accessible to all. Together, we can continue to challenge oppressive narratives, amplify marginalized voices, and work toward a more just world.