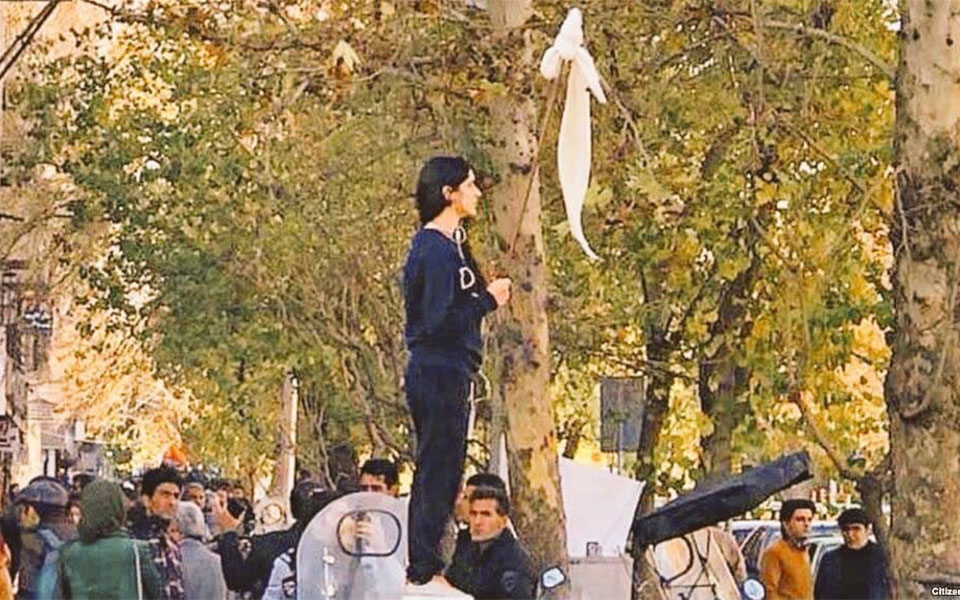

Photo caption: Vida Movahed was a young woman who took to the podium on the main street of Tehran in the winter of 2017 to protest the forced hijab and discrimination against women and tied her scarf to a piece of wood. Her initiative sparked similar acts across Iran known as the Girl of Enghelab Street.

The oppression of women in societies that practice Islam is well documented. Resistance to this oppression dates back to the late 19th century, when women emerged as a new social force with their own journalism, literature, and political organizations. The oppression of women and resistance against it is one of the key themes in the literature of the region including Arabic, Kurdish, Persian/Dari, and Turkish. During the early 20th century, the democratic and independence movements considered gender equality and ‘women’s rights’ to be markers of a new world. As early as 1911, a member of the newly formed Iranian parliament tried to persuade legislators to grant women suffrage rights.

However, the new nation-states that were formed after the First and Second World Wars tried to suppress women’s movements. ‘State feminism’ is the practice of controlling this new social force by closing down women’s groups and their press, forming a single government-sponsored women’s organization, and giving women certain rights like education, property ownership, unveiling, and employment opportunities. In countries such as Egypt, Iraq, Iran, and Turkey, secular regimes made numerous compromises with religion, especially in personal status legislation.

Under republican Turkey and monarchical Iran, religious institutions were suppressed and put under strict state control. Nevertheless, there was no serious separation of state and mosque in constitutions, laws, or political culture.

After an anti-monarchist revolution in Iran, the establishment of the Islamic Republic changed the dynamics of gender relations in the region. The founder of the state, Ayatollah Khomeini, viewed the separation of state and religion as a conspiracy against Islam, so he merged them. He began a vast Islamization project, which targeted women first and foremost. In less than a month from assuming power, Khomeini dismissed women judges, and required all women to observe dress codes such as veiling and covering their body according to Islamic principles. Despite resistance, gender segregation was gradually imposed, often through coercion.

Unlike the Islamic theocracy of the Taliban in Afghanistan, where women were subjected to a regime of total gender apartheid, Iranian women were allowed to be present outside the home. However, the policy was gender segregation, similar in many ways to racial apartheid. Iranian theocracy, like its Afghan or Saudi Arabian counterparts, denies women the right to unrestricted presence in public and private spaces. Whether at home or outside, women have to ‘protect’ themselves or be ‘protected’ from namahram men, i.e. males who are not fathers, brothers, husbands or sons. In public spaces such as city buses, schools, concerts or line-ups, males and females are segregated. Moreover, women and members of religious minorities have been constitutionally and legally denied the right to be ‘supreme leader,’ president, or judge. Also, shari’a-based laws seriously curtail women’s rights in many areas including travel, divorce, marriage, dress, custody of children or inheritance.

Some observers, including Iranian nationalists, emphasize the conspicuous difference between Iranian and Taliban theocracies, and find the former much more tolerant of women. They refer to the active presence of Iranian women in all domains of public life, including journalism, publishing, higher education, parliament, government, cinema and the market. This is clearly different from the Afghan situation, where women were allowed only to live and die within the confines of their homes, and to reproduce the male gender.

However, one may argue, as Israeli scholar Uri Davis has done in comparing Israeli and South African apartheid regimes, that Afghanistan’s gender apartheid is ‘petty’ compared to that of Iran. Davis has noted, for instance, that in Israel there ‘are no benches designated in law for “Jews only” and other benches for “non-Jews”; buses for “Jews” and “non-Jews”… ’ Still, ‘in all matters pertaining to the question of rights to property, land tenure, settlement and development, Israeli apartheid legislation is more radical than was South African apartheid legislation’.

By way of analogy, Taliban gender apartheid may be considered crude or ‘petty’ in so far as it was based on full segregation of the population on the basis of gender only. By contrast, gender apartheid in Iran keeps the semblance of tolerance of women, is carefully legislated by the parliament, and is enforced through both consensus and coercion, including a network of courts, prisons, police, vigilante groups and surveillance.

While in Afghanistan the Taliban ruler was law-maker, judge and executive, in Iran the Islamic parliament acted as the legislator, and a Council of Guardians ensured that all legislation conformed to Islamic principles. The unicameral parliament does, however, look like a multi-faith institution with elected members from Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian communities. The Islamization of the ancient Iranian state, which Khomeini inherited, was achieved through the re-writing of its extensive legal apparatus, and replacing it with an equally extensive legal order rooted in the theology of a rather small sect of Islam, the Twelver Imam Shiism.

No doubt, the Taliban theocracy was much more coercive in enforcing gender apartheid. Moreover, if the lives of women in Afghanistan have not changed visibly since the overthrow of Taliban by the USA, Iran’s theocracy and its gender apartheid are in the process of disintegrating largely due to the unceasing and all-round resistance of Iranians, with women as the engine of change.

Khomeini’s theocratic nation-building project and its Islamization of gender relations amounted to a disruption of the way political life had been evolving in the region since the end of the 19th-century, especially Iran’s Constitutional Revolution of 1906–11. This change involved, in part, the trend of separation of state and mosque, and a few steps towards legal equality in gender relations (e.g. recognition of women’s suffrage rights in Turkey 1930, Pakistan 1947, Syria 1949, Lebanon 1952, Iran 1963, Afghanistan 1964). Not surprisingly, the founding of the new theocratic regime in 1979 led to political, theoretical and ideological cleavages in and outside Iran. In fact, feminists, women’s rights activists, human rights advocates and those dealing with the Islamic world have been sharply divided over Islamic gender politics.

One side of the great divide tolerates or justifies discrimination against women by arguing that gender relations in these societies are based on religion and culture, and it would be inappropriate to label them as ‘oppression’, ‘discrimination’, ‘inequality’ or ‘injustice’, because such claims are rooted in western cultural values. This is the position of secular observers who adhere to ideas of cultural relativism. Islamists base their position on the sanctity and divinity of Islamic foundations of gender relations, although they also appeal to cultural relativism. The other side of the divide starts from the standpoint that gender relations are constructed by human beings, and religion, culture, tradition or custom are some of the sources of inequality. From this perspective, there is nothing sacred about any patriarchal regime. They are constructed socially and they can be dismantled.

The divide is by no means along ethnic lines, although one side appeals to ethnicity, i.e. religion and culture, in order to defend an Islam-based regime of women’s rights. This is not an East–West or a Muslim–Christian divide, although it is often presented as such. In fact, there are people of diverse cultural and religious backgrounds, both easterners and westerners, and religious and secular on each side. Moreover, far from being monotonous, each side of the divide forms a spectrum of theoretical, political and ideological positions. There is a considerable literature that reflects the range of debate between the two poles. However, the conflicting positions within each side have not received adequate research attention. This article demonstrates a major rift among the group that defends women’s rights from a universalist and internationalist perspective. This is a Marxist–feminist critique of liberal universalist politics.

Patriarchy: A social system

In several Middle Eastern nations, there has been a noticeable reversal of women’s rights since 1979. Both men and women in the region have resisted this patriarchal shift through various means, such as advocating for their rights. International documents like CEDAW and others from the UN have played a significant role in supporting this ongoing struggle. For instance, Iranian lawyer Mehrangiz Kar conducted a comprehensive study comparing Iran’s Islamic laws with the articles of CEDAW, revealing consistent conflicts between the two. Similarly to Mayer, Kar argued that shari’a is not inherently divine and unchanging, suggesting that there is potential for reform within the legal system to align with CEDAW principles.

While the legal reform of Islamic gender relations is certainly possible and necessary, they will not put an end to the patriarchal regime. From a Marxist-feminist perspective, patriarchy is a social system; it is not a product of misbehavior, misunderstanding, or mis-education, although all of these may be present in individual cases. Patriarchy is a system in which two genders coexist in hierarchical, unequal and oppressive relations. In this system, males exercise gender power and dominate the other gender. It not only produces women’s subordination but, like other systems such as capitalism, ‘produces the conditions of its own reproduction’ (in the words of Marx, quoted in Himmelweit, 1983: 417). Ideology, religion, education, custom, force of habit, language, law, music, dance, among others, create consensus as well as conditions, which restrain resistance to patriarchy. There is an interdependence of these systems. For instance, the economic system, capitalism or pre-capitalism, thrives on the paid and unpaid labor of women. In North America, popular culture and mainstream media propagate anti-feminism.

Patriarchy operates independently of other social structures while also relying on them. Its influence extends beyond religious institutions, even in theocratic nations such as Iran, and transcends economic systems’ class dynamics. Legal equality, when applied to gender, is insufficient to restrain, let alone dismantle, such a system. In the context of patriarchal systems within Islamic theocratic states, reforms based on Islamic law may serve to mitigate state-sanctioned gender-based violence.

This article was written by Iranian researcher and academic Shahrzad Mojab. She is a women’s rights activist who has conducted extensive research in this field. The present article examines one of the most important aspects of women’s rights in Iran and the Middle East. This article offers a Marxist-feminist critique of liberal approaches to the conflict between women’s rights and religious and cultural belonging in societies that practice Islam.

The Persian text of this article was published on the Bidarzani website, which belongs to a group of women’s rights activists in Iran, and you can read the original text in English from here.

.

Support The Fire Next Time

I started this space with a simple but urgent goal: to speak freely and honestly about Iran—beyond the headlines, beyond the usual narratives. Inspired by James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, this blog is a place for difficult conversations, for challenging power, and for amplifying the struggles of those who are too often silenced.

Independent writing like this doesn’t have corporate backing or institutional support—it exists because of readers like you. If you believe in the importance of a space that pushes back against repression, that refuses to look away, and that insists on telling the truth, I invite you to support this work.

You can help sustain my work by becoming a member on Patreon:

Click here and choose an option

Your support not only helps keep this space alive but also ensures that these critical discussions remain accessible to all. Together, we can continue to challenge oppressive narratives, amplify marginalized voices, and work toward a more just world.