(on the occasion of the camp in Eleonas)

In the general view of Greek and EU authorities, controlled close camps or, more specifically on my side, imprisonment has become the response of first resort to far too people who are ensconced in refugee management crisis and racism. As a result of poor camp conditions, and the resulting harms and violence, migrants are framed as dangerous and deviant, as undesirable, and as risky instead of at risk. It is masked by being conveniently grouped together under the category “illegal immigrants” or “asylum seekers” and by automatically classifying people as criminals. Homelessness, unemployment, drug addiction, mental illness, and illiteracy are only a few of the problems that disappear from public view when the human beings contending with them are relegated to cages.

presenting migrants as threatening and deviant serves to absolve the state of responsibility towards them and can be an effective strategy to alleviate any guilt felt about their suffering. In effect, this not only justifies withholding humanitarian assistance, it also legitimises the use of punitive, even violent, means to control migrants.

Statics

There are about more than 16,000 people living in camps across Greece, comprising people who are waiting for their asylum claims to be heard and those who have had their claims accepted or denied. After the enactment of border restrictions, a total of 32 mainland camps were operating in December 2020, most of which were temporary accommodation facilities. Due to the continued drop in arrivals in 2021 (roughly 42% drop from 2020) coupled with the dramatic increase in reports and allegations regarding pushbacks at the border, these temporary accommodation facilities were reduced to 25 by December 2021.

It has emerged that new catering contracts for the provision of food in these camps provide enough food to feed just more than 10,000 people, covering only those still in the asylum procedure and not those who had their asylum claims accepted or rejected. Which they forcefully have to leave the camps after receiving their notification. This comes despite calls from the European Commission that the Greek government ensures all persons, particularly the vulnerable, receive food irrespective of their status.

In a number of cases, asylum seekers and refugees residing in mainland camps continued to protest against substandard living conditions, their ongoing exclusion from the Greek society, and the new policy of excluding those not eligible for reception conditions from the provision of food, amidst severe delays in the distribution of cash assistance.

Struggles

In October 2021, residents of Nea Kavala camp protested by obstructing entry to the camp, while calling to for food not to be cut. Small tensions were reported in April, amid a protest in Skaramangas camp which was scheduled to close without, reportedly, the residents being informed of where or if they would be transferred ad how their housing needs would be met after the camp’s closure. In November, residents of Oinofyta camp barred entry to the camp for at least two days, protesting for the ongoing rejections of asylum claims lodged by Kurdish nationals, on account of the Greek Asylum Service’s persistent application of the “safe third country” concept in the case of Turkey.

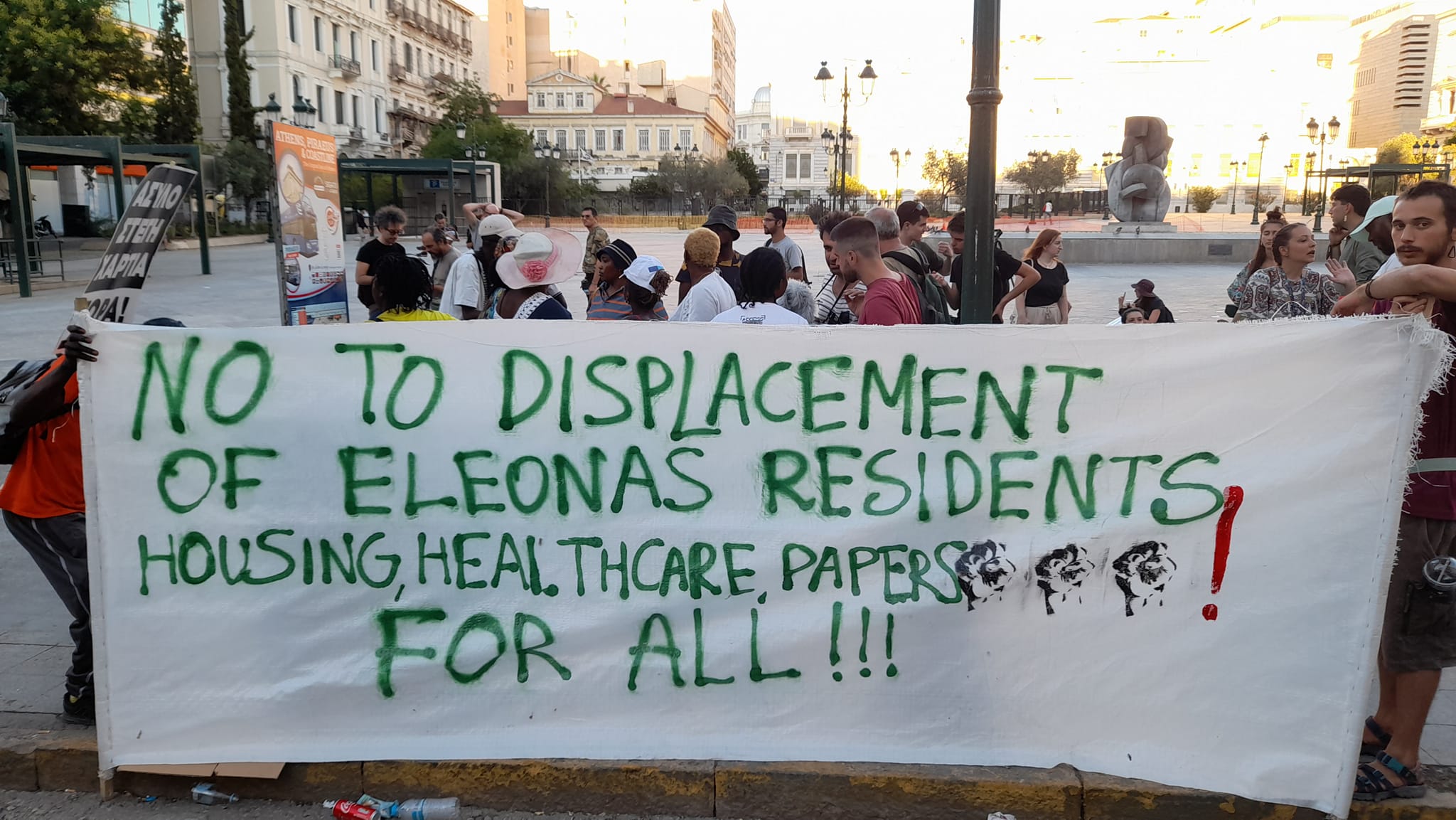

In the same month, refugees in Elaionas camp also protested, calling for the site to not be closed and for procedures to be accelerate. As stated, by a woman from Somalia, “The municipality wants to transfer us from here, but where can we go? We have children that go to school, we have people that work in the city. Why do they want to remove us from here and where can we go?”. There are still protests going on.

As a result of the Ministry’s decision not to renew the social workers’ contracts in June 2022, Elaionas camp residents will no longer be able to exercise their rights to health, education, and asylum. The Ministry has also ordered restriction on movement of residents and is using an outdated and erroneous camp enrollment list in order to prevent entry of people staying at the camp.

A closure of the Elaionas camp would result in hundreds of residents being forced to relocate to camps outside Athens with limited access to healthcare and education. Undocumented people are also subjected to exploitation, blackmail, and deportation threats in these concentration camps.

In the past three years, there have been increasing numbers of xenophobic and racist incidents targeting asylum seekers being transferred to mainland reception facilities, newly arrived refugees and migrants, as well as staff of international organizations and NGOs, civil society activists and journalists, because of their association with the defense of refugee rights. These attacks have escalated with physical attacks on staff providing refugee services, in shelters and NGO vehicles, and blocking the transfer or disembarkation of new arrivals with racist remarks.

Although such practices may ostensibly contradict the tenets of the EU, states have always operated on the premise that those labelled “others” or less than human do not deserve the equal status of human beings.

the influence of neoliberalism and chauvinism

It is a form of governmentality to portray migrants as a threat, because the state uses power to create security for some (worthy of protection) while removing it from others (necessary sacrifices). Thus, these “illiberal practices” are part of the European project, with concepts such as “the rule of law” and “good governance” being effective tools to oppress and exclude others through non-racialised, objective, technocratic methods. Consequently, the harm suffered by refugees trapped in camps is not in opposition to neoliberal governance, but rather instrumental to it. In addition to ameliorating the harms caused by such “illiberal practices,” humanitarian actors contribute to their continuation by providing aid and assistance to camp residents, which sustains the camps.

Among the left, political analysis without taking into account the political economy of war, Fascist (religious and nationalist) tendencies involved in war in countries like Afghanistan and Syria, or the lack of interest in the political conditions and life in countries like Iran (with its fake anti-imperialist status) contributes to the development of these ideas.

In these years, however, we have not seen a practical or realistic struggle to defend or support refugees. As an example, in the summer of 2020, dozens of families without the support of the local movement, were forced to leave Victoria Square after days fighting for residency documents due to several police attacks, and were trapped in very difficult and exhausting conditions in the camps.

However, the origins of refugees and their class base are seldom considered and generally in the analysis avoided as part of their social position, which inevitably reflects a continuity of class and history. The viewpoints of these groups emphasize the refugee issue from the perspective of refugee-accepting states or local movements, and typically remain silent about refugees’ countries of origin or limit themselves to political generalizations without analyzing why people move.

In this way, any criteria and benchmarks regarding the human exchange potential of the refugees are forgotten and they become identical individuals without characteristics; That is: in terms of the personality, identity and social demands of the refugees, they are ignored in production relations; And the slogan of defending the right to asylum for “everyone” takes on a radical and serious appearance. But since “everyone” is simply an abstract concept in the elimination of features and usually means nothing, instant of practical actions on refugee movements, we have social democratic propaganda scandals.

For this reason, when talking about the closing of the refugee camp, the needs and demands of the refugees (such as the right to register an asylum application, the right to have residence documents, and accelerating asylum procedures) are generally ignored, and the dominant discourse is, Opposition parties’ criticism of the ruling party’s performance, urban planning and gentrification.

It is evident here that “others” and other needs are part of the picture.

.

My journey in creating this space was deeply inspired by James Baldwin’s powerful work,

“The Fire Next Time”. Like Baldwin, who eloquently addressed themes of identity, race, and the human condition, this blog aims to be a beacon for open, honest, and sometimes uncomfortable discussions on similar issues.

Support The Fire Next Time by becoming a patron and help me grow and stay independent and editorially free for only €5 a month.

You can also support this work via PayPal.

.

.

What you think?