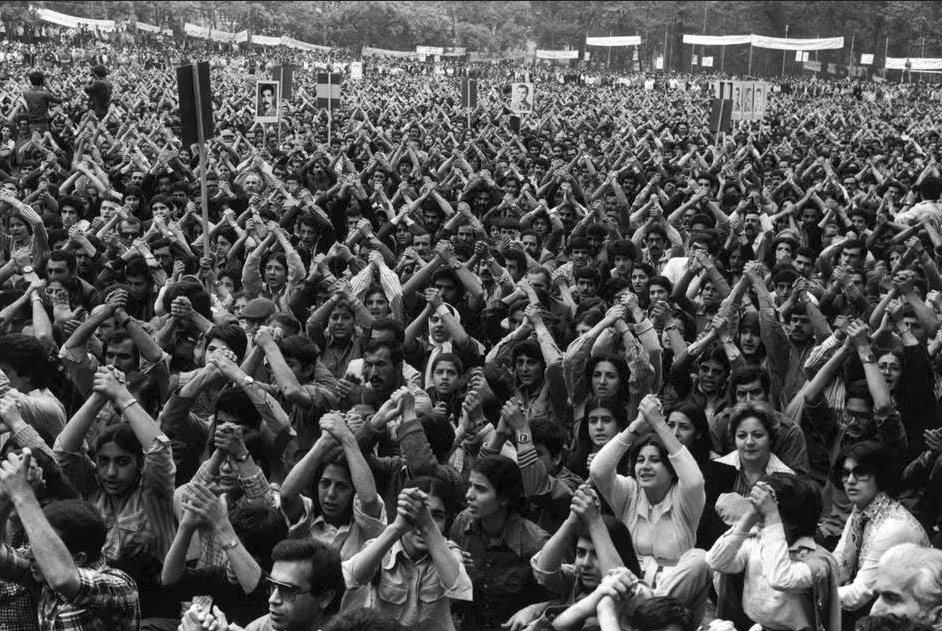

Photo: Gathering of members of the Organization of Iranian People’s Fedaii Guerrillas at Tehran University, February 1979.

The article, “Socialism or Anti-Imperialism? The Left and Revolution in Iran,” written by Val Moghadam, delves into the complex interplay between various ideological currents within the Iranian Left during the country’s revolutionary period. Valentine Moghadam is a feminist scholar, sociologist, activist, and author whose work focuses on women in development, globalization, feminist networks, and female employment in the Middle East. Moghadam starts her article by this sentence “Aspectre is haunting the Iranian Left—the assembled ghosts of orthodox Communism, Maoism and populism.”

The article offers a profound analysis of the ideological landscape of the Iranian Left before and after the 1979 Revolution. It highlights the Iranian Left’s commitment to anti-imperialism and its critique of dependent capitalism, which was a common thread among various leftist factions, including orthodox communists, Maoists, and populists. The article references Karl Marx’s observation about making history under unchosen conditions, aptly applying it to the Iranian Left’s experience, which was fraught with challenges and unexpected turns:

The outcome of the Iranian Revolution recalls Marx’s observation that we make our own history but never under conditions of our own choosing. It recalls also, only too painfully, his comment about the ‘dead weight’ of the past. Finally, it demonstrates that not every anti-capitalist or anti-imperialist action is an advance towards socialism. But these lessons have been learnt at enormous cost: the stunning defeat of the Left in the mini-civil war of 1981–83, its displacement from the arenas of political and cultural struggle, extreme disillusionment, retrenchment, a wave of depoliticization—and, of course, the deaths of many, many worthy comrades.

Must Iranian leftists today are extremely—one might say, excessively—critical of the whole period from 1970 to 1978, often bordering on self-cancellation and repudiation of the efforts of an entire generation. But it should be pointed out that the general theoretical problems which they faced were shared by left organizations, particularly ‘m–l’ Maoist groups, everywhere. The focus on guerrilla activity was not the sole reason for the marginalization of the Left in Iran—after all, a guerrilla strategy was used with great success by the Sandinistas in Nicaragua.More importantly, the Left was not isolated after the overthrow of the Shah in February 1979: on the contrary, it had a huge following. The Fedaii, for instance, had some 150 offices throughout the country and one of their rallies was attended by five hundred thousand people. But if the numerical strength of the Fedaii, Tudeh, Mojahedin and Peykar added up to considerable political potential, unity was sadly never near the top of their priorities.

The article was penned a year before the massacre of leftist political prisoners and remains influenced by the self-critical debates of the Iranian left. The leftist movement, which its radical wing had established the Communist Party in the mountainous regions of Kurdistan under the leadership of Mansoor Hekmat in the early 1980s, and was actively involved in a guerrilla struggle against the emerging Islamic-capitalist regime.

The clergy had all the government posts by that time. Mojahedin-e-Khalq (MEK) had assassinated scores of leading Islamic Republic Party (IRP) members since Bani-Sadr’s ouster. There had been several street battles between left-wing organizations and the IRGC, the government militia linked to the IRP. The Kurdish people continued to fight the central government for self-determination, and there is new unrest among the Azerbaijanis in northwest Iran. Back then, the IRP’s claim of a massive turnout for their candidate in the presidential elections clearly was a lie while leftists and many journalists in Tehran believed that not more than a third of the claimed eligible actually voted.

The Islamist’ strength was based, however, not solely on votes or religious faith but on its veritable army of thugs, the Hezbollah. These gangs had fight against the leftist parties and militant workers from the beginning, and had succeeded in carrying out an IRP campaign to “Islamization” the universities, a left stronghold; Bani-Sadr demonstrated his impotence by doing nothing to stop the arrests, killings and university shutdowns. During 1981 when the IRP had governmental power this harassment has become a full-scale massacre.

Unlike the Shah, who never had any mass support, the IRP had built mass organizations to mobilize small merchants, artisans, and some workers behind it. The Islamist already had a mass base on which to build, the Muslim congregation. Using the traditional prayer services, and setting up neighborhood committees and factory Islamic societies, as well as the Hezbollah and IRGC thugs, the priests had set up the framework for the control of many aspects of daily life by the government and ruling party.

Other aspects of fascism strictly defined was easy to find, the supreme leader who stand above classes was, of course, Khomeini. The Islamic judges who occasionally jailed or even executed capitalists for price-gouging or ties to the U.S. stand in the fascist tradition of regimenting a capitalist class too decayed to discipline itself. The “corporatism” of the neighborhood committees, Friday prayer services, and factory Islamic Societies went together with Persian and Muslim chauvinism to enforce the “unity of all classes” against “alien influences” allegedly responsible for dividing Iranians against each other. In line with this, the massacre of the military attacks against Kurdish society who rejected the Islamic state, along with a campaign against members of the Jewish and especially Baha’i religions which threatens to become literally genocide.

Moghadam examines the struggle of leftist groups in this circumstances to navigate the tumultuous landscape marked by the overthrow of the Pahlavi monarchy, the rise of Islamic governance, and the Iranian Left’s quest for relevance and impact. This exploration is critical in understanding how ideologies like Marxism, Maoism, and populism intersected and clashed with the reality of a nation in upheaval, and how this ideological conflict shaped the Left’s strategies and outcomes.

Banner text: “Long live proletarian internationalism”

One of the central themes of the article is the Iranian Left’s underestimation of the power of Islamic clergy and its neglect of the question of democracy. This oversight, as the author notes, was largely due to the Left’s excessive focus on the anti-imperialist struggle, leading to strategic errors. The article also underscores the surprise that the Islamic Republic’s establishment posed to many, including foreign observers and scholars who had previously supported the Iranian Left for its anti-imperialist stance.

The historical backdrop, including the role of Mohammad Mosaddegh and the Tudeh Party, is crucially dissected, providing insights into the complexities and internal conflicts within the Left. The Shah-CIA coup against Mosaddegh’s government is highlighted as a pivotal moment that led to a reorganization of the Left and a new round of dictatorial rule. This historical context sets the stage for understanding the Left’s challenges and transformations during the revolutionary period:

In 1951, Mohammad Mosaddegh became the Prime Minister of Iran with the primary goal of implementing the oil nationalization law. His focus on this issue led to neglecting other important matters like workers’ rights and land reform, causing discontent among trade unions linked to the Tudeh Party. Further, the Ministry of Labour stopped registering new labor unions from May 1952, likely to curb communism’s growth. Mosaddegh’s steadfast opposition to Soviet oil concessions increased the Tudeh Party’s hostility towards him, which was compounded by the U.S. establishing closer ties with Iran’s police and military.

Additionally, Mosaddegh faced opposition from the Shah, religious leaders, and foreign powers like the UK and the USA, who were against the nationalization of their oil companies. Tudeh supporters’ protests for a republic and against the monarchy were met with police brutality. The situation escalated in August 1953 when Mosaddegh declared the Shah’s dismissal of him as illegal, leading to a coup that overthrew his government. This event not only toppled Mosaddegh’s nationalist government but also significantly suppressed the Tudeh Party and the trade union movement. The coup was supported by various internal and external forces, including significant religious figures, and was backed by the CIA.

One of the prominent clerics that supported the US and British coup against the Mosaddegh state was Ayatollah Abol-Ghasem Kashani, who later Ayatollah Khomeini developed a close relationship with him. Declassified US documents reveal that unlike Ayatollah Khomeini, Abolqasem Kashani did not mince his words when speaking with US agents, openly expressing his intention to unite a million-strong army of Muslims to combat imperialism. Despite the respect with which his words were acknowledged, the US agents privately referred to him as an extremist, opportunistic, and delusional individual, whom they sought to either win over or neutralize in their efforts to overthrow Mohammad Mosaddegh.

The article also sheds light on the Pahlavi regime’s policies, such as the White Revolution, which aimed at capitalist accumulation and agrarian reform. These policies significantly impacted the socio-economic landscape of Iran, leading to urbanization and the growth of a semi-proletariat class. Furthermore, the regime’s attempts to control traditional commercial and financial operations ignited opposition from various quarters, including the Bazaar and clerics, setting the stage for the Revolution.

Another significant aspect discussed is the adoption of dependency theory by the Iranian Left, which emphasized Iran’s political dependence on the United States but failed to recognize the regime’s potential autonomy, a critical analytical flaw. The diverse analyses of Iran’s economy by various Left groups also highlight the ideological plurality and disagreements that plagued the Left.

The author critically examines the Left’s failure to engage with the cultural realm, particularly its treatment of Islam and its compatibility with socialism or Marxism. This lack of engagement is contrasted with the approaches of figures like Jalal Al-e Ahmad and Ali Shariati, who offered a radical populist Islamic critique of Western influence:

Those who did write about culture and religion—Jalal Al-e Ahmad and Ali Shariati—postulated resistance to de-culturation and Westernization; they advanced a critique of Europe and the United States from a radical, populist, Islamic and Third Worldist perspective—not a socialist one. Unfortunately, this emerging revolutionary-Islamic culture did not become a terrain of contestation. The Fedaii seemed to be ignorant of it; the Tudeh Party may have consciously decided not to take it on; and the Mojahedin borrowed freely from its discourse.

The neglect by the secular Left of such issues as social psychology, cultural forms and religion allowed the Rightists and religious contributors to the journals Maktab-e Islam and Maktab-e Tashayo to dominate the cultural realm and imbue the anti-imperialist discourse with denunciations of the West, of Marxism, of Christianity, and of secularism. In a kind of populist patriotism that eventually proved their downfall, the secular Left did not maximize differences in order not to appear divisive or to splinter the opposition to the Shah. By contrast, the religious forces had only open disdain for the Marxists. In prison in the mid1970s, certain clerics who later took power in the Islamic Republic would refuse to eat with the communist prisoners.

Your support helps keep this space alive but also ensures that these critical discussions remain accessible to all.

Moghadam’s work provides a detailed analysis of the Iranian Left’s situation during the anti-Shah struggle and the early stages of the Islamic Republic. It highlights the fragmentation and weaknesses of leftist groups due to prolonged repression in the 1960s and 1970s, which prevented them from playing a significant leadership role in the mass movement or influencing the anti-dictatorship discourse. The Fedaii and Mojahedin organizations, having lost many key members to executions and imprisonment, faced notable disadvantages like weak social connections, lack of continuity, and leadership gaps:

When the anti-Shah struggle broke out, the Iranian Left was as divided as its counterparts in Europe and North America and less securely rooted than the religious opposition in Iran. Because of sustained and systematic repression during the 1960s and 1970s, none of the Left groups was in a position to play a leadership role in the mass movement, or to define or influence the discourse and strategy of the struggle against the dictatorship.

The Fedaii and Mojahedin had suffered particularly severely. Nearly all the founding members and top cadres of the Fedaii—some two hundred people—had been killed in prison executions, under torture or in shoot-outs with the police. These included Bizhan Jazani, Massoud Ahmadzadeh, Amir-Parviz Pouyan, Behrouz Dehghani, Marzieh Ahmadi Oskooi and Hamid Ashraf—talented, dedicated and experienced women and men whose deaths deprived the communist movement of effective leadership and continuity.

Other Fedaii cadres were in prison during most of the 1970s, and were only released following the liberation of the prisons in early 1979.footnote21 In the intervening years, some of these activists had been drawn to Tudeh thinking in the course of discussion with other prisoners, and after the Revolution their opposition to more militant anti-regime policies eventually led to a split in the Fedaii organization. Others, upon release, formed smaller groups (such as Rah-e Kargar), which were sympathetic to the Fedaii organization but diverged on some issues.

Thus the Fedaii organization entered the political arena in late 1978 and early 1979 with certain distinct disadvantages: a lack of strong links with, and bases among, key social forces, such as urban industrial workers and the semi-proletariat, due to both the regime’s repression and their own guerrilla strategy; a lack of the continuity, sustained leadership, size and unity that could have provided a firmer basis for action; a communist orientation and Marxist-Leninist tendency in a context marked by radical-populist Islamic fervour and extremely uneven socio-economic development.

The poster text: “Without the participation of women, no revolutionary movement can achieve victory.“

Despite these challenges, leftist guerrilla groups, especially the Fedaii, played a crucial role in the revolution, actively participating in armed uprisings and gaining public support. However, their lack of continuous leadership contrasted with the more stable Mojahedin and Tudeh Party structures. The inability of major leftist organizations to unite or offer an appealing program to various social strata marked a significant shortcoming, providing no viable alternative to the emerging political authority of the mullahs and the ‘liberal bourgeoisie’.

For instance, one of the events during which the Peykar party found itself in a sharp turn that was not coherent with its analyses and left its members confused for a period was the seizure of the American embassy on November 4, 1979. In this historical event, revolutionary students supporting Imam Khomeini, later known as the “Students Following the Line of Imam,” attacked the American embassy demanding the extradition of the Shah and took the embassy staff hostage.

In fact, the seizure of the US embassy was considered the first major challenge for the organization after the revolution; because this anti-imperialist action was carried out by the revolutionary youth of the Imam’s line, and the organization had to take a clear stance in rejection or approval of this act. In other words, the organization had to consider the main instigators of this action as an anti-imperialist force; such an interpretation, although to some extent could be significant within the framework of the political analyses the organization had provided until then, was, however, leading towards a counter-revolutionary characterization of the ruling petty bourgeoisie faction in its political analyses, especially after the months of July and August. Until the embassy occupation event occurred, the organization in its analysis was identifying this faction as a counter-revolutionary force. But with this incident, the organization became confused.

Ultimately, the party did not assess this action as an anti-imperialist move and instead presented it as a confrontational act against the liberals, carried out by the ruling petty bourgeoisie faction and the Islamic Republic Party. It was perceived within the context of conflicts and disputes between the two ruling factions. With this analysis, for the first time, the organization not only labeled the entire regime but also the petty bourgeoisie faction, including the Imam’s line, the Islamic Republic Party, and others, as counter-revolutionary, despite the differences that the organization believed existed among them.

The Islamic regime managed to undercut the Left in many more ways than through its populist–radical economic and social practices. One was the resort to anti-imperialist political actions such as the seizure of the American Embassy in November 1979, which met with the approval of Ayatollah Khomeini and was widely popular among Iranians in general. Another was sheer intimidation and brutality, which began fairly early on. Self-styled ‘partisans of God’ (Hezbollahi) regularly harassed leftists, and in August 1979 eleven Fedaii were executed in Kurdestan by Revolutionary Guards.

Early in 1980, in the northwestern region of Turkaman Sahra bordering the Caspian Sea, the regime ruthlessly put down a cultural–political movement of the ethnically Turkic population who were supportive of the Fedaii and had received assistance from them in the organization of numerous peasant cooperatives. Four Fedaii leaders (all Turkamans) were kidnapped and murdered. In April the ‘liberal’ President Bani-Sadr endorsed the initiation of the ‘Islamic cultural revolution’—an invidious twist of the Maoist formulation. This led to confrontations with university councils and especially with radical students affiliated to various Left groups. For the next two years, all the universities and some high schools were shut down while the curriculum was duly islamicized and left-wing faculties purged.

The post-revolution period saw a complex situation of dual sovereignty between the Provisional Government and the Revolutionary Council of Ayatollahs, with Ayatollah Khomeini gaining mass support. This period posed significant challenges for the Left, especially in balancing political and ideological integrity with pragmatic considerations. The expansion of the Left during this period led to the formation of various new groups and organizations, each with its distinct ideologies and support bases.

The analysis critically examines the different leftist groups’ strategies, ideological stances, and their implications in the rapidly evolving political landscape of post-revolution Iran. The Fedaii’s popularity, the Mojahedin’s hierarchical organization, Peykar’s strict opposition to the new regime, and the Tudeh Party’s bureaucratic influence are all discussed. Additionally, the involvement of Kurdish groups, various Trotskyist parties, and smaller Maoist factions showcases the ideological diversity within the Iranian Left.

The split within the Fedaii organization, the challenges faced by the Mojahedin and the Tudeh Party, and the Left’s inability to effectively respond to the new Islamic regime further illustrate the complexities and dilemmas faced by the Left during this period. The article also addresses the ways in which the Islamic regime managed to undermine the Left, through both populist economic policies and intimidation tactics.

In conclusion, the article offers a detailed and nuanced examination of the Iranian Left’s ideological struggles, internal conflicts, and responses to the rapidly changing political landscape during a critical period in Iran’s history. It provides valuable insights into the challenges of aligning ideological principles with pragmatic political strategies in times of profound societal upheaval.

The slogan on the banner: Any form of tyranny is condemned.

Various Iranian leftists are diligently collaborating on diverse projects focused on the working class, intellectual history, modernism and anti-modernism in Iran, deconstructing the populist discourse, as well as delving into the history of Islam, urban and regional planning during the transition. Authored by dedicated intellectuals, these studies markedly contrast with the dispassionate and unembellished accounts found in most readily available secondary sources on Iran.

These works exude a sense of urgency, commitment, and purpose, as they are penned by individuals who have personally and politically grappled with the repercussions of incomplete, schematic, and superficial knowledge about their society. Consequently, there exists a deliberate effort to bridge the gaps, refine existing comprehension, and promote fresh perspectives and interpretations. Gradually, a transformative vision of genuine modernization, democratization, and the cultivation of a new cultural identity (or identities) is taking shape.

The socialist tradition in Iran has faced tumultuous times, marked by errors, tragedies, and setbacks. However, it has shown remarkable resilience and endurance. Despite disruptions, brutal massacre, oppression, and the persistent challenge of passing down knowledge from one generation of activists to the next, Marxist and Leftist discourse holds substantial influence in Iranian society. Unlike in many other societies, socialism in Iran is not synonymous with failed policies in power, authoritarian politics, or corruption. Iranian socialists are yet to be tested and have to prove themselves. Considering these factors, there is potential for the Left to re-emerge in the political sphere and shape an Iranian practice, an Iranian idiom, and an Iranian path towards socialism.

The industrialization process in Iran did not coincide with cultural transformation and social and intellectual advancement. It didn’t become a model like Western countries. Being associated with dictatorship, despotism, coexistence and compromise with religion and patriarchy, a new model of capitalism emerged in the world. It was different in both its workers and capitalists. The worker became a cheap, oppressed, and deprived labor force, while the capitalist remained backward, merely maintaining the framework through despotism.

Focused not on progress but on maintaining a closed and tyrannical system. This was because a cultural process was needed for landowners to become capitalist lords. This process even cut across its own class. That’s why you don’t see liberalism in the Middle East. You don’t have the traditions of Western capitalism. Even its nationalism is extremely rural and obsolete. There’s no political tradition. In 1979, with Islam, everything changed. Remember, Khomeini flew over Tehran in an army helicopter, with Shah’s Generals support. It was the Shah’s army that wrote to Khomeini, welcoming him and ready to join him.

The experience of the left in Iran can provide valuable insights into the understanding of mistakes and confusions within the global leftist movement. It is particularly noteworthy that the global left, adopting a similar political mindset to some factions of the Iranian left in 1970-80s, is at risk of aligning with right-wing and counter-revolutionary inclinations, and dangerously at even this time, siding with fascism. This presents an opportunity for reflection and recalibration within the global left.