After several decades, we think that Western intellectuals in 1979 were mistaken about the Iranian Revolution, or, at best, were deceived by the words and behavior of Islamist who oppressed the revolutionaries and the “tricks” of the their leaders. But this is true? Can we add that these were intellectuals who described and explained events with an Orientalist perspective?

The most significant example to prove this hypothesis is the views of Michel Foucault, one of the main symbols of intellectuality at that time, about the revolution in Iran and their roll in manufacturing the term of Islamic Revolution. However, reducing the entirety of “Western intellectuality” to the person of Foucault cannot represent the whole truth of the matter, because during that period, besides the author of the “History of Madness”, there were other radical intellectuals who came to Iran or better to say, to Tehran the capital during the revolution and had completely different positions regarding the developments in the country and even its not-so-bright future. One of these individuals was Kate Millett, an US pioneering feminist.

Before the publication of “Foucault and the Iranian Revolution” in 2005, out of the fifteen writings and interviews by Michel Foucault about the Iranian Revolution, only three had been translated into English.

When in March 1979, coinciding with the revolutionary executions and the demonstrations of Iranian women on March 8th against the hijab, the book “Iran, the Spirit of a World Without Spirit” (which was the result of Foucault’s conversations regarding the Iranian Revolution before the establishment of the new regime) was published in Paris, almost everyone pointed the finger at Foucault’s political naivety. Editorials in newspapers like Libération, Le Nouvel Observateur, and others became the places to attack his political views, especially in a context where the new actions of the Islamic state opened the way for any criticism against him.

Just as Foucault himself wrote after the establishment of the Islamic Republic, it seemed that the Iranian people also considered their revolution a mistake because of its outcome – the new government. Foucault and many intellectuals preferred to either ignore the realities of suppression and the civil war that the Islamic current launched against the 1979 revolution or claim that they were unaware of it. Didier Eribon, Foucault’s friend and biographer, talks about the psychological damages Foucault suffered because of the controversy over this issue; damages that for a while led Foucault to remain silent on matters related to politics or at lest, international issues.

Millett and Foucault had notable similarities. Both were close to the liberal left-wing, wrote significant books in their fields, intervened in protests in other countries, were homosexual, and took a stand against the suppression of the government during the Pahlavi era. Despite these, the two had opposing views on the Islamic Revolution. This shows that one cannot generalize about a concept called Western intellectuals, just as it is not entirely accurate to speak of a uniformity among Iranian revolutionaries.

Sexual Fantasies of an Orientalist

What attracted Foucault to revolutionary Iran was the widespread presence of men ready to die and boys seeking martyrdom in the streets of a country in the heart of the Middle East. He witnessed the presence of men from a specific political orientation in Tehran. Having lived in Tunisia before, he had a special attraction to Arab men and male gatherings in the Middle East and was somewhat influenced by the hippie cult, which was intertwined with exotic Eastern concepts.

In Iran, he saw things he had only imagined in his dreams: a vast multitude of men willingly facing death, collective movements of boys seeking martyrdom, the strong smell of male sweat wafting through the streets, rows of tense muscles, and an apocalypse of dark eyes and olive skins. Always fascinated by “death and the male,” he saw revolutionary Iran as the embodiment of his promised paradise. That’s why he used a theological term to describe the atmosphere of Iran at that time: spirituality. Spirituality was nothing but the moment of realizing a sexual utopia; the moment of merging male homosexual Eros and the heavenly Thanatos of Orientalism.

Years after the Iranian Revolution, Foucault spoke of another utopia elsewhere: a suicide club. He expressed a desire to establish a society where people, specifically men, would gather together and, after several days of complete debauchery and fulfilling all their desires, would commit suicide. This ideal society was not unlike the society of Iran during the revolution for Foucault. Men eagerly and poetically embracing death, infusing the wide and exotic streets of Tehran with spirituality, and of course, the enticing smell of male sweat.

For Foucault, Iranian women were essentially nowhere to be seen. This absence of revolutionary women in his perspective is not coincidental, as he had not paid much attention to them in his works either. As Marie-Jo Bonnet writes, Foucault fundamentally did not “see” women, and his interest in men was so pronounced that he considered them the primary representatives and subjects of history. For instance, in “The History of Sexuality,” a very minimal portion is dedicated to female desire, and in “The Will to Knowledge,” there’s scarcely any mention of female homosexual Eros. It was the revolutionary men in Iran, with their unique fury and bravery, who captivated him, not anything else. Of course, women were also present in the streets, but not for Foucault.

The critiques aimed at Foucault generally fall into three categories: Some relate it to a kind of Orientalist inclination within Foucault himself. Others consider various aspects of his expression, specifically highlighting the author of sexuality’s neglect of issues related to women, homosexuals, and religious and ethnic minorities. The third group directs their criticism towards Foucault’s explicit or implicit support of political-Islam.

Where are the women?

Unlike Foucault, Kate Millett paid more attention to the presence of women in the streets during that time. She, along with a group of Western intellectuals and artists, came to Iran immediately after the revolution’s victory to participate in the first women’s day demonstration in the history of Iran. In addition to her, several other French and American feminists of the time were present in Iran, but many of them left the country after a few days when the government’s pressure on women intensified. For instance, Sylvie Braibant, a well-known French activist and artist, is one of those who gave up on documenting in Iran and returned to Paris, disillusioned and angry, on the first flight after Ayatollah Khomeini’s decree on the mandatory covering of women in government offices. Kate, who also intended to make a documentary about women’s presence in the revolution, stayed in Iran longer than her friends and even ended up being arrested and interrogated.

“Men, men, men, everywhere men.” These are the words Millett uses to describe the presence of men, and in fact their unwarranted intervention, in the streets of Tehran. She sees things in Tehran that part of these society at the time did not notice, namely that revolutionary men intend to claim the revolution that women also participated in as their own.

On March 8th, she is out in the street with other women, but repeatedly sees men either attempting to disrupt the gathering with violence or, with a supposedly compassionate gesture, trying to “educate their sisters” that the current priority of the revolution is other important issues. To her utter disbelief, she observes that even on Women’s Day, women are not allowed to speak, and the platform is constantly given to know-it-all men.

During the march, Millett sometimes becomes so enraged that she angrily asks the Iranian men present on the street to leave: “I wish men would go away… This is a women’s demonstration. Why don’t you get lost.” At another point in the same demonstration, she tells one of the Iranian women, who is arguing with an Iranian man, “It’s really important not to pay attention to the men. They never listen. Why waste your time? You’re in a women’s gathering. Why should you talk to men in a women’s demonstration?”

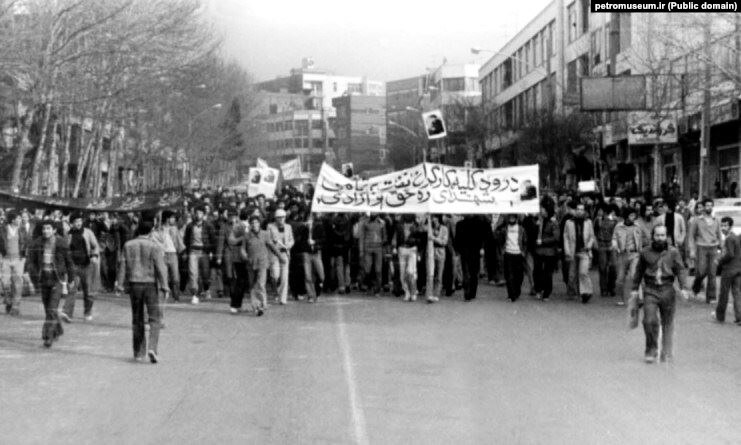

Banner: “Tyranny is condemned in any form.”

Millett was particularly concerned about the mandatory imposition of the hijab. She believed the function of the hijab, especially the black chador, was to erase women from the revolution. The uniform black chadors took away women’s individuality, rendering half of the society invisible by homogenizing them. The most significant crisis occurred when a group of French women activists intended to interview Ayatollah Khomeini. The revolutionary leader would only accept the interview on the condition that all women wore the hijab. The French women were divided: some believed they should not succumb to this imposed condition, especially since Iranian women had just demonstrated for their right to choose their clothing, while others argued that the historical opportunity of interviewing the revolutionary leader was worth the compromise of putting a piece of cloth on their head.

To resolve their disagreement, they called Paris to seek the opinion of Simone de Beauvoir. De Beauvoir, sternly, opposed the interview: “What nonsense is this? Why should you interview Ayatollah?” Nevertheless, led by Claire Brière, who had interviewed Khomeini before the revolution, some of the women went to Qom and wore the hijab for the interview with the revolutionary leader. The conversation lasted only ten minutes, during which Khomeini, with indifference and disrespect, left most of the French women’s questions unanswered. This interview became a significant defeat for the feminists in Tehran. They realized what Ayatollah’s deception meant and were deeply disheartened and disillusioned. The next day, several tickets to Paris were purchased. Millett left a few days later. Iranian women stayed behind, along with several dark decades.

After returning to US, Millett somewhat shifts her stance in her memoirs of her time in Iran, praising the rare group of Iranian men who fought alongside Iranian women towards realizing feminist ideals. From Millett’s perspective, such unity is rarely seen in the West, and Iran could serve as a suitable model for other countries in this regard:

“Being alongside men in the Women’s Day demonstrations is a strange feeling, a delightful one. Men who risk their lives and become the target of merciless ridicule for standing with us. Men who endanger their safe spaces because they will be attacked before we are. No man in America has ever risked his life, or limbs, for his belief in women’s freedom, no man in the West, no man in any world I had known before. And seeing those men in Iran, you had to love them… Men who fight for our cause, on our behalf, peacefully, for the first time in history.”

Foucault viewed the role of religion and the suppression of the revolution in Iran not as an institutional element, constructed from traditional power relations, but as a popular, anti-despotic, and anti-colonial element through which people manifested their will. However, Foucault, of all people, should have been more aware of such potentiality in religion, given how could the author of “Discipline and Punish” and “The History of Sexuality” be unaware of institutional analysis of mechanisms of repression, discipline, and control over sexuality, judiciary, social, and other systems in religious regimes?

Foucault, in some of his articles, attempts to answer that a distinction must be made between fundamentalist Islam and other interpretations of Islam. He and others, while turning a blind eye to the authoritarian potentials of a theocratic state, highlighted these differences to justify their theories, despite the fact that they themselves would not be willing to live under the laws and culture of a Christian theocratic state. It is here that one can comfortably say that he was engulfed in his Orientalist fantasies. Islamists constructed the same image of the East that in his fantasies was nothing more. It seems Foucault had hope that the Islamists in his fantasy behave differently from what the right-wing in Europe claims about them.

My journey in creating this space was deeply inspired by James Baldwin’s powerful work, “The Fire Next Time”. Like Baldwin, who eloquently addressed themes of identity, race, and the human condition, this blog aims to be a beacon for open, honest, and sometimes uncomfortable discussions on similar issues.

Support The Fire Next Time by becoming a patron and help me grow and stay independent and editorially free for only €5 a month.

You can also support this work via PayPal.

.

What you think?