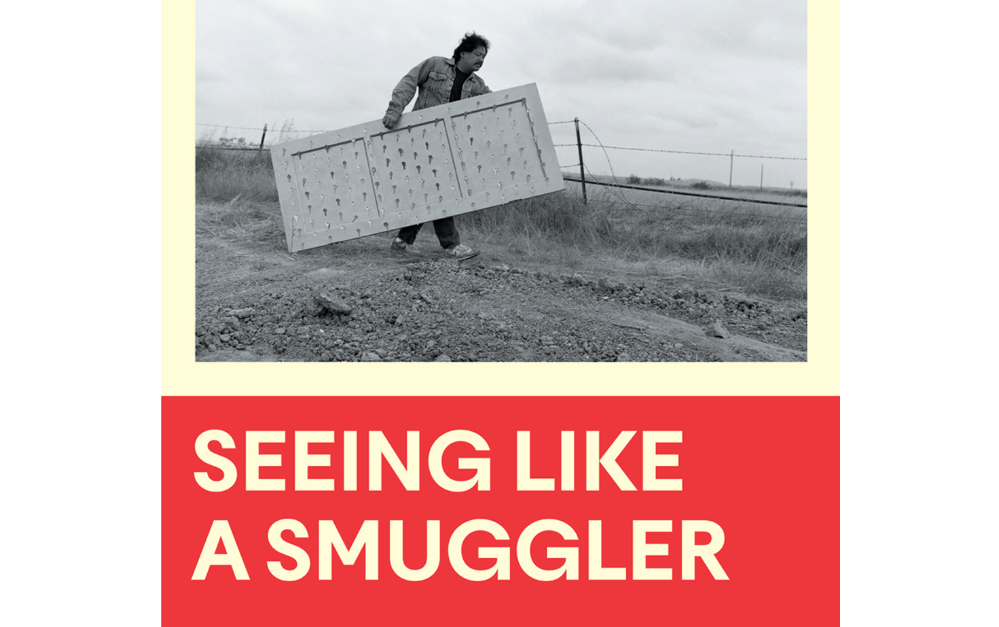

Seeing Like a Smuggler, Borders from Below is a 2022 book by Mahmoud Keshavarz and Shahram Khosravi

Smuggling is given to us as something hidden, under-reported, or else it is overly-evident – transparent – news cameras waiting for migrants on the beaches of southern Europe. But do these simplistic images of a diverse and changeable circulation like smuggling really offer us a sensible approach to the subject?

What is actually offered up to us? This paper will consider the shortcomings of transparency as a socio-political ideal and, in particular, smuggling’s relation to it. Turning this around, the semi-secrecy inherent in it, and partial offerings out of it, might provide us with new subjectivities and critical positionalities that totalizing transparency precludes. What might it show for itself and, by implication, if we see as a smuggler, how are we thereby empowered? I shall work through these issues with some historic and contemporary examples of on-the-ground smuggling before considering how they can offer an alternative track for interdisciplinary research, exchange of ideas, and new knowledge production.

From the book

With the rise of oil economies in the 1980s and the rise of labor mobility, Ethiopia has historically had close ties to Saudi Arabia through trade, religious pilgrimage, and labor mobility. Between 2009 and 2014, nearly half a million Ethiopian labor migrants entered Gulf Cooperation Council countries – mainly Saudi Arabia and the UAE (United Arab Emirates) – of whom more than 90% were women, mostly unmarried and less educated. There are approximately 1 million Ethiopian migrants living in Saudi Arabia at the moment. For the most part, these migrants are believed to have entered Saudi Arabia through smuggling services in Wollo, an area of northern Ethiopia that is predominantly Muslim.

Despite Saudi Arabian deportations of 170,000 Ethiopian migrants between 2013 and 2015, the vast majority of deportees re-migrated to Saudi Arabia using the services of smuggling networks.4 There is a well-established overland migrant smuggling route that links Wollo and Saudi Arabia: the route starts in northern Ethiopia and passes through the Afar region in eastern Ethiopia, it exits through Djibouti, crosses the Red Sea and proceeds to Saudi Arabia via Yemen. The route passes through towns such as Kombolcha, Gerba, Degan and Bati in Wollo then proceeds to Djibouti via the towns of Mille, Logiya, Semera, Whalimat, Desheto and Galafi in the deserts of Afar region, and Tajora and Hayu in Djibouti.

During the 2010s, the Ethiopian government expanded its control of infrastructures and introduced tough regulations and policies to stem clandestine migration. This was mainly due to pressure from receiving countries. However, smuggling has increased since then and complex forms of clandestine international border crossing have emerged. Smugglers provide their services to migrants by generating and using certain knowledge about borders, states and labor markets in destination countries. Contrary to the popular assumption that it is an isolated criminal activity, smuggling is socially embedded and is part of the everyday lives of the local residents in origin countries and migration routes. Family networks, traders, religious leaders, pastoralists in border areas, ordinary people and local officials are all involved in smuggling activities.

This chapter considers migration, the smuggling structures that mediate it, and border control as complementary and co-constitutive processes which produce one another. It is based on extensive ethnographic fieldwork conducted between 2018 and 2019 in various departure and transit locations in Ethiopia such as Wollo, Addis Ababa, and Afar Regional State, as well as along the Ethiopian-Djibouti border.5 Interlocutors included smugglers, potential migrants, returnees, deportees and government personnel involved in migration, facilitation and control processes.

In the next sections, I will first elaborate on smuggling organizations and pathways. Next, the knowledge and networks of smugglers, the sociocultural and community dimensions of smuggling, and its ethical and political implications will be discussed. Finally, I will reflect on the logic, practices, and functions of smuggling, and its relationship to larger structural issues.

The knowledge and networks in smuggling

There are various tasks, positions and actors that function together to facilitate a journey. For example, the lekami (literally ‘picker’) is a contact person who meets potential migrants and collects them in a village or a town. Another actor is wana delala (literally ‘main broker’) who gives general guidance and provides directions from a strategic migration origin, a transit location, or a destination. Agachoch (literally ‘interceptors’) are a group of smugglers, often nomads and armed people in Yemen, who collect migrants arriving by boat on the Yemeni side of the Red Sea shores. Each type of smuggler has their own role, though there is sometimes an overlap. For instance, the wana delala may also act as a recruiter or as a lekami in a village where they have good social relations and trust among the local community. The lekami may perform the roles of agachi and wana delala. The leqamiwoch work at the kebele (local area) and district level. Their main job is collecting contact details of potential migrants and linking them to the wana delala.

Hamud, a man in his late thirties, was wana delala in Dessie town, the capital of Wollo district. I met him in March 2018 in Dessie Town Administration Prison as he was serving a long sentence for human smuggling in the region. He said he worked with many lekami in different villages and districts in both South and North Wollo Zone. He spoke of the specific knowledge and resources of smugglers: ‘lekami knows the migrant. I know the routes and I have contacts at all points.’

The role of the main delala is providing guidance, transport, food and shelter for potential migrants along transit locations. This is the person who knows about timings, routes, borders and control structures along the routes. Hamud states:

I was a wana delala in Kombolcha town for a long time and I used to send different migrants to the Middle Eastern countries. There were different lekami who were working for me. The lekamis used to bring or send their clients to Kombolcha. I have [sic] different mechanisms of hiding potential migrants in Kombolcha. For example, there was one grocery in which I used to hide them. If we suspect staying in the grocery might be risky, we usually shift to hotels, different pensions, compounds, and tea shops. After I receive potential migrants from my lekami, I, in turn, send them to Afar. In Afar, particularly in Deshoto [a town at the Ethiopia-Djibouti border], I had another person who facilitated everything for me. Taking migrants as far as Deshoto was my role.

Bringing migrants to the Ethiopia-Djibouti border is not a simple task as there are several checkpoints along this migration route. Smugglers carefully work with different actors. They may secure support from border agents at various checkpoints, or they may use diverse transport strategies. Smugglers often transport migrants during the night, and they do not always take their clients by themselves, but instead use a variety of methods, depending on the context. If migrants can be transported in one vehicle, smugglers will transport them by themselves, but when their number becomes too few, smugglers transfer them to another delala to take along with his migrants. Migrants claim that smugglers or delaloch have their own style of communication, which is full of codes and difficult for others to comprehend when they communicate and broker with one another. During phone conversations, smugglers often use the language of commodities. As Hamud reports: ‘When I communicate with my agents over the phone, I tell them I have sent them 10 sacks of sugar, instead of 10 migrants.’

Lorries are used to transport potential migrants from Kombolcha to Desheto. When brokers use lorries they do not load them with people alone, but use other commodities as a cover. One delala stated: ‘we make the car to have [sic] two partitions by using rope or wood at the bottom and at the top. We often load people at the bottom and other commodities (bottle cases, egg, tomato, and other things) at the top.’

The agachi wait for migrants on the Yemeni side. The Yemeni and Ethiopian agachi work together. The Ethiopian agachi also serve as translators between migrants and Yemeni agachi during the deals and interactions in Yemen before migrants proceed to Saudi Arabia. The agachis have their own shelters and safe houses in Yemen. They have their own vehicles for transportation, guns and communication devices. Using these resources and connections, they facilitate migrants’ clandestine journeys through Yemeni territory and across the Saudi border, despite the ongoing war, violence and tightening border control apparatus along the Saudi-Yemeni border.

The agachis collect migrants from the seaside and transport them to their camps or safe houses, often by Land Cruiser Toyota, a four-wheel drive vehicle for off-road driving. The smuggling process beyond Yemen is similar to those within Ethiopia. However, this part of the journey requires more resource and knowledge due to the war in Yemen and tough controls along the Saudi-Yemeni border. According to a returnee who was deported from Saudi Arabia, the agachi act like the military soldiers and armed resistance groups in the Yemeni desert:

They put their vehicles in a row. The car in a front line is always intentionally kept empty. It is used as a gatekeeper and guide … the rest of convoy which are behind. … The front car checks and scans the security conditions and passes over information for others. The command is from the front; if they need to retreat or use other short path; all this is determined by the flow of information from [the] front guide car.

This shows one way in which smugglers develop knowledge about the working of borders in a particular location. Smugglers develop these strategies to transport migrants through war-torn and unstable Yemeni territories. Once migrants arrive at the safe house the agachi require every migrant to name the delala they dealt with. They then ask each migrant to pay money in cash or transfer money via hawala agents to pay for the agachi and the meshiwar (lit. ‘smuggler adviser’). The meshiwar is a smuggler in Yemen who guides and transports migrants from Yemen to Saudi Arabia, usually for the fee of SAR (Saudi Arabian Riyal) 6,000 (about €2,000). Transferring money through hawala agents is done by migrants who have anshi, that is, a relative who resides in Saudi Arabia and is willing to collect them by paying the meshiwar in Yemen. For those who have anshi, they are simply requested to give the address and contact number of this person. Other issues like negotiations regarding payment are dealt with by the meshiwars and the anshis.

If a migrant does not have cash to pay, they are first divided into two groups by the meshiwars: those who have anshi and those who do not. Migrants claim that those who have anshi are treated better by meshiwars. The meshiwars leave migrants who cannot pay by cash or through anshi under the burning sun in the desert. If migrants refuse to give an address of someone who can transfer money and pay the smuggling fee, they are beaten. Hamud stated:

There will be no tolerance for such kind of issues. There are people called gerafi [whipping person] who are responsible for beating and torture [sic] migrants. Most people in the beginning used to say, ‘I don’t have anshi’. But when they taste the stick, you find them say that they have many people who can help them.

Under torture, one is forced to fabricate an anshi or lie to save themselves. According to the smugglers, migrants are asked whether they have money or anshi before they get into the Donik (boat) in Djibouti. Boarding the Donik is not allowed if they do not have money or anshi. Hamud stated:

Everybody says, I have anshi when they are taken to the boat in Djibouti, but refuses to pay after arriving in Yemen. We are not providing services for free. They have to pay us! When they fail to pay, we have no other option than to whip them.

Such are the views of smugglers about their violent actions. They justify beating or torturing migrants as a result of a failure by clients to live up to the agreement.

Sometimes migrants run away from the safe-houses of meshiwars and walk to the Saudi border on foot, a journey which is possible thanks to the assistance of local people who offer them food, provide directions and give other forms of assistance. Migrants who had travelled the route previously and have some Arabic-language skills help others with translation and guidance. Migrants take up any employment offered without hesitation once they have crossed the Saudi border. Once they have crossed the border, migrants move towards big cities in Saudi Arabia. Migrants claim that the local people in Saudi border areas are familiar with the arrival of Ethiopian migrants and approach migrants with job offers. Communications and salary deals are done by sign language or writing on the sand when they meet on the streets.

.

.

My journey in creating this space was deeply inspired by James Baldwin’s powerful work,

“The Fire Next Time”. Like Baldwin, who eloquently addressed themes of identity, race, and the human condition, this blog aims to be a beacon for open, honest, and sometimes uncomfortable discussions on similar issues.

Support The Fire Next Time by becoming a patron and help me grow and stay independent and editorially free for only €5 a month.

You can also support this work via PayPal.

.

What you think?