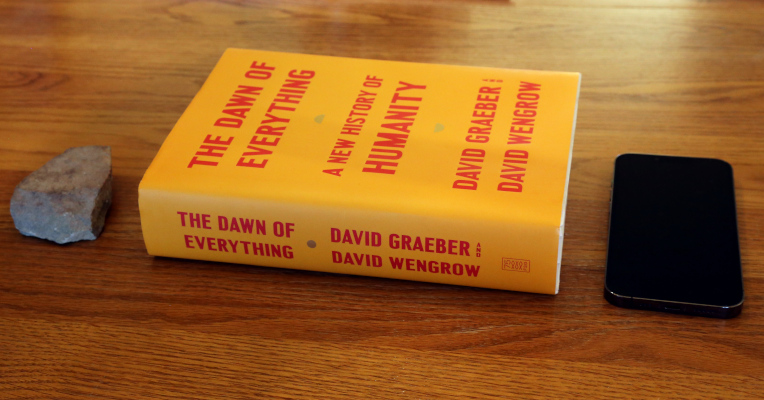

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity is a 2021 book by anthropologist David Graeber and archaeologist David Wengrow.

We like to think that prehistoric humans were simpler than we are. We might even think they were stupid – think cavemen and -women dragging clubs around and gnawing raw meat. Of course, these depictions are far from accurate. The Flintstones is not a documentary. But these ideas point to a deep-rooted idea, an idea long espoused by philosophers and intellectuals – that people in the past weren’t capable of abstract political thought or social organization. We now know that this isn’t true.

New findings show that prehistoric peoples were certainly political. They not only fought about political arrangements; they discussed and debated those arrangements. The archeological and anthropological record paints a clear picture: prehistoric societies were more complex, and more interesting, than we’ve long believed.

When it comes to how human society developed, there are two opposing stories.

The first one comes from the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and it goes like this: Once upon a time, we were all hunter-gatherers. We lived in small bands, and everyone was more or less equal. Then came the advent of agriculture. We figured out how to cultivate plants and animals, and we stopped hunting and gathering. This agricultural revolution led to more complex political structures, not to mention advancements in cultural phenomena such as the arts, philosophy, and literature. It also spawned hierarchical phenomena like patriarchy, mass execution, and interminable bureaucracy.

The other story was developed by a decidedly grumpier thinker, the English writer Thomas Hobbes. His story goes like this: Humans are, at their core, selfish creatures. In the past, life was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Hierarchy and domination, he believed, have always been an aspect of human society.

So which story is true? Most social scientists would answer: a bit of both. But when you look at the evidence, including an ever-increasing archaeological archive, it becomes clear that the bit-of-both answer is also unsatisfactory. You see, both stories posit linearity. That is, they both argue that, from a pre-civilized condition – be it Rousseau’s condition of equality or Hobbes’s condition of hierarchy – we evolved into our current “civilized” state. But when you examine the evidence and think carefully about it, the truth is that human society did not develop linearly. Civilization did not march forward. It marched sideways, it went backward, it stood still. And, anyway, the “marching forward” metaphor is silly and misleading, since it’s not necessarily accurate to think that our society is better than those that preceded it.

So why is it so hard for us to imagine alternatives to the stories of Rousseau and Hobbes?

Early societies were a lot more complex – and interesting – than we’re taught to believe. These blinks seek to restore our ancestors to their full humanity, showing that many more possibilities for political organization and social interaction exist.

In the 1690s, a leader from the Huron-Wendat people in North America sat down with French colonists in Montréal to debate a variety of socio-political topics. His name was Kandiaronk, and his French interlocutors loved him. They described him as both witty and singularly brilliant. A book of his ideas sold like hotcakes throughout Europe, and inspired a response from nearly every Enlightenment thinker.

To put his views very simply, Kandiaronk was curious to understand why people in Europe were so obsessed with money and private property. And – come to think of it – why did their kings have so much power, whereas everyone else had practically none. What’s all this poverty about? Why do people put up with it? He didn’t hold back: “I have spent six years reflecting on the start of European society and I still can’t think of a single way they act that’s not inhuman…”

His criticisms were brutal, and they both shocked and excited Europe’s philosophers. But Kandiaronk’s views weren’t unique. They were shared by many indigenous people after coming into contact with European colonists. They became known at the time as the indigenous critique.

For conservatives in Europe, the indegenoius critique just wouldn’t do. To undermine North American indigenous critiques of European culture, right-wing thinkers began dismissing indigenous people, and their ideas of individual freedoms and social checks on authoritarianism, as “savage.”

European society was simply more advanced, further along the inevitable path toward “civilization.” Indigenous peoples hadn’t even begun marching. Sure, in Europe, there was poverty, domination, and religious persecution. But these losses of freedom represented a much larger gain: the achievement of a true civilization.

The term “egalitarian” became a default to describe societies without the trappings of what these Europeans called “civilization,” a kind of imaginary utopia left over when one strips away things like judges, kings, and overseers. Conservatives even blamed the links of Kandiaronk for the violence of the French Revolution, asserting that they’d introduced new, liberal ideas into a stable social hierarchy.

But of course, lumping together so many communities and societies as idyllically, unrealistically egalitarian tells us less about those communities, and more about the culture that needed to define itself against them.

In the end, if we are to understand how modern systems of domination came about, we need to set aside the question of equality or inequality. Instead, we need to work out why kings, princes, and overseers emerged.