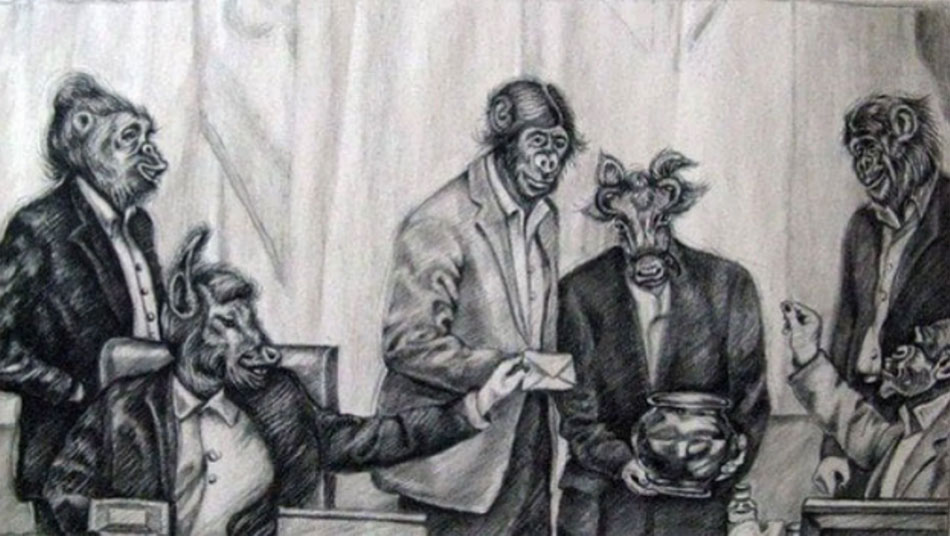

Cartoon: A cartoon depicting the Iranian government as a bunch of dumb monkeys and goats by Atena Farghadani. The cartoonist was imprisoned for over two months for publication of this cartoon.

It is still a question for many why the Iranian Revolution morphed into a clearly antagonistic authoritarian religious government, opposing the freedom-seeking and independence-seeking ideals of the leftist third-worldism, or how the Palestinian liberation movement, which was an inspiration for transnational solidarities globally, turned towards Islamic fundamentalism?

This note introduces the newly published book “The Fate of Third Worldism in the Middle East: Palestine, Iran and Beyond,” which attempts to provide answers to these questions.

Third-worldism represents a political doctrine that surfaced in the late 1940s to early 1950s amidst the geopolitical tension of the Cold War. Its foundational principle was to foster solidarity among the countries that chose to remain neutral and not align with either of the two superpowers of the time, the United States or the Soviet Union.

But the term used in this book as an umbrella term covering a range of related ideas and ideologies connected across time and space to national liberation movements in what was then considered ‘The Third World.’ In the words of Robert Malley, Third-Worldism was ‘a political, intellectual, even artistic effort that took as its raw material an assortment of revolutionary movements and moments, wove them into a more or less intelligible whole, and gave us the tools to interpret not them alone, but also others yet to come.

In the latter half of the twentieth century, a revolutionary idea promised to upend the global order. Anti-imperialist militancy, bolstered by international solidarity, would lead to not only the national liberation of oppressed peoples but universal emancipation, shattering the division between the prosperous nations of the capitalist West and the poorer countries of the Global South.

The idea was Third Worldism, and among others it inspired struggles in Iran and Palestine. By the early 1980s, however, progressive visions of independence and freedom had fallen to the reality of an oppressive Islamic theocracy in Iran, while the Palestinian Revolution had been eclipsed by civil war in Lebanon, Israeli aggression and intra-Arab conflict.

This thought-provoking volume explores the dramatic decline of Third Worldism in the Middle East. It reveals the lived realities of the time by focusing on the key protagonists – from student activists to guerrilla fighters, and from volunteer nurses to militant intellectuals – and juxtaposes the Iranian and Palestinian cases to offer a riveting re-examination of this defining era. Ultimately, it challenges us to reassess how we view the end of the long 1960s, prompting us to reconsider perennial questions concerning self-determination, emancipation, change and solidarity.

Oneworld Academic

This book, adopting a “global history through local history” approach, aims to link the micro-histories of individual, social, and political-ideological movements in Iran and Palestine with their transnational intertwinements, and especially focuses on the late 1970s and early 1980s, to interpret the broader history of third worldism as a global phenomenon from the perspective of the historical context of the Middle East, particularly Iran and Palestine.

“The Fate of Third Worldism in the Middle East: Palestine, Iran and Beyond.” It is edited by Rasmus Christian Elling and Sune Haugbolle and was published in early January of this year by OneWorld Academic, as part of the “Radical Histories of the Middle East” series. The book spans 320 pages and includes 11 chapters, along with an introduction and a conclusion.

Rasmus Elling is a professor of Iranian studies and the head of the Department of Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark. He is also the author of “Minorities in Iran: Nationalism and Ethnicity after Khomeini.” Sune Haugbolle, on the other hand, is a professor of global studies and the head of the Department of Global Sociology at Roskilde University in Denmark, and a researcher specializing in the history of the left in the Middle East, particularly in the Arab world.

The book “The Fate of Third Worldism in the Middle East” is divided into three parts. The first part, consisting of three chapters, deals with the ideas and struggles of third worldism on a transnational (or international) scale. The second part, which includes four chapters, is dedicated to the intra-regional scale of third worldism. The third part, also comprising four chapters, explores this history on a national scale.

From the book’s introduction

The aim of this book is to revisit a time when the power of third-worldism in one of the world regions, which until then had been a strong harbinger for change, reached its peak and then dramatically declined. The period in question includes the historical turning points of the late 1970s and early 1980s in the Middle East. Specifically, this book focuses on two struggles for freedom and national sovereignty in Western Asia – namely in Palestine and Iran – which were significant not only for political developments in the wider region but also for the global solidarity movement.

Asef Bayat, who holds the position of Professor of Global and Transnational Studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and is a distinguished scholar in the field of social movement theories, offers his remarks on the back cover of this volume:

“What happened to the ideology of third-worldism, which once promised to lead the oppressed peoples of the world towards a broad sense of freedom and liberation? In this valuable book, the authors examine the decline of one of the most influential revolutionary ideologies on a global level, the implications of which cannot be underestimated for the practice of radical politics in today’s Middle East.”

According to the book, while the revolutionary discourse across the Middle East was dominated by leftist movements in the 1970s, it became apparent in the early 1980s that Islamism had transformed into a powerful political trend, if not entirely dominant. This shift can be traced in the ideological-political transformations of countries like Iran, Yemen, Iraq, Syria, Libya, Egypt, Lebanon, and the Palestinian movement. In these countries, socialist regionalism and Marxist internationalism were challenged by Islamic revivalist movements.

Marral Shamshiri, the distinguished historian and civil activist, meticulously utilizes obituaries as a lens to dissect prevailing issues concerning gender dynamics within the context of revolution in the fourth chapter of her work. Through a detailed examination of Rafat Afraz’s passing, Shamshiri deconstructs the revolutionary obituary, positing it as an artifact of transnational significance particularly within the scope of Third-Worldist revolutionary discourse. She undertakes a critical analysis of its creation, distribution, and subsequent interpretation.

Shamshiri’s investigation uncovers the intricate interconnections that emerged between Iranian and Arab revolutionary initiatives, thereby probing deeper into the gendered narratives and broader implications for women within the revolutionary milieu. Her argument foregrounds a stark contrast: the public image of the militant revolutionary female starkly differs from the actual political engagement of Iranian women, especially in the context of the Dhufar Revolution. The constructed narratives on martyrdom frequently disregarded the tangible political contributions of these women, instead opting to lay claim to the political symbolism of their deceased bodies.

The initial section of the chapter delves into the nature of the revolutionary obituary as both a historical document and a transnational artifact. Shamshiri tracks its journey across the ideological landscapes of Iranian and Arab revolutionary cells, revealing the relationships and networks formed by Iranian revolutionaries that extended across the Middle East.

The subsequent section is a case study that meticulously traces Rafat Afraz’s obituary as it traverses through networks spanning South-South connections and into the heart of student-dominated urban centers. This exploration sheds light on the contesting narratives that swirl around the legacy of martyrdom and the portrayal of women’s roles and lives in the revolutionary activities orchestrated by various Iranian political factions.

Section goes beyond narratives of martyrdom by exploring the experiences of Rafat Afraz and revolutionary Iranian women in Dhufar, showing that there was a gendered division of labour which was erased in narratives of women’s armed political participation as circulated through the obituary. Finally, the fourth section explores how dead Iranian women’s bodies have become sites of political contestation when claimed in state-funded historiographical debate within Iran.

1979: A Turning Point?

Why did third-worldism, as a liberating and anti-imperialist ideology in the global south, particularly in the Middle East of the late 1970s, experience a decline? What happened to the slogans and ideals of international and revolutionary solidarity with oppressed peoples? How did the secular figure of the ‘Fedaii’ transform into the religious-Islamic figure of the ‘Mujahidin’?

These are some of the questions that the book “The Fate of Third Worldism in the Middle East” seeks to answer, focusing on the late 1970s and the first half of the 1980s.

Haugbolle and Elling explain in the introduction that the general idea of the book is that the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s marked the formation of a new social order in the world, primarily referred to as neo-liberalism. This global situation, in interaction with the historical-social and economic structure of the Middle East, led to a significant transformation in the ideas and political movements of the left in the Middle East, marking the weakening and decline of third-worldism in the region.

The editors believe that while the reconstructive trends of 1979 should be sought throughout the 60s and 70s, the year 1979 itself is a turning point in these global and regional transformations, considered a crucial year for third-worldism in the global south, especially the Middle East. Haugbolle and Elling view 1979 as a turning point not just for the Middle East but for the entire world.

Globally, policies of free market capitalism began in China from December 1978, the wave of socially-conservative and economically-neoliberal policies of Margaret Thatcher – Thatcherism – from 1979, and similar policies by U.S. President Ronald Reagan from 1981, all representing the emergence of a new global politics based on free-market capitalism, deregulation, privatization, weakening of collective agreements, attacks on the welfare state and Keynesian economic policy in Europe.

In 1979, the Middle East also underwent fundamental changes. Egypt, the former leader of Arab nationalism and state socialism, shifted its economy towards foreign investment and made peace with Israel. In Saudi Arabia, 1979 marked the emergence of opposing radical religious currents in the Sunni world, gaining momentum in response to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979. This invasion led to nearly a decade of military conflict between the Soviets and the Mujahideen, among whom future leaders of jihadist terrorist groups like Al-Qaeda and ISIS emerged.

In Iran, the 1979 revolution created an environment for a state project of political Islam that played a decisive role in shaping political Islam in the entire region. Also, Israel’s invasion of West Beirut in the summer of 1982 marked the end of the revolutionary phase of the Palestinian struggle and its main representative, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), leading to its transformation into a state-like institution in the West Bank in the 1990s.

Saddam Hussein became President of Iraq in July 1979 and started a devastating war with Iran a year later, lasting until 1988. In Turkey, a military coup in 1980 led to the marginalization of leftist currents in favor of religious fundamentalism.

upon establishment, different strands of the new Iranian government had their own reasons to embrace open, friendly relations with the PLO. In need of a new regional ally, PLO leader Yasser Arafat, a practising Muslim himself, was happy to highlight the Muslim heritage of the PLO to appease Ayatollah Khomeini and the clerics close to him.9 During Arafat’s trip to Tehran immediately after the February 1979 revolution, Israel’s former embassy in Tehran was handed over to the PLO. The ‘representative of the Palestinian Revolution’, Hani al-Hassan, was in fact the PLO’s official representative in Tehran and the embassy’s incumbent officer.

At the same time, however, Islamists were naturally aware of the PLO’s leftist inclination and its financial and political ties to both Sunni-majority Arab countries and the Soviet Union. While other revolutionary groups such as the Islamist–Marxist Sazman-e mojahedin-e khalq-e Iran (the People’s Mojahedin Organisation of Iran, MEK) and small internationalist groups openly engaged with, supported, and sought assistance from the PLO, the Islamist and domestically oriented Islamic Republic Party (IRP) had to find a more nuanced approach to support the Palestinian cause while refusing to endorse the PLO’s unfavourable history and connections.

and next to Khomeini, his son Ahmed and one of the most notorious Sharia judges, Khalkhali.

The year 1979 marked the end of the heyday of Marxist liberation movements in the world, pivoting the locus of revolutionary power from Third Worldism to Islamist transnationalism. It also marked a confounding turn for the PLO and liberation movements that had thrived in the era of secular and left-wing transnationalism. They came to Tehran with the hope of solidarity against US imperialism and the Israeli occupation. By contrast, for their Iranian hosts, the gathering was a response to a global counter-revolution, led by both Eastern (Soviet) and Western imperialism. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan reinforced their perception that both East and West imperialists sought to surround and confine the Islamic Revolution within the borders of Iran.

Chapter 5, Brothers, Comrades, and the Quest for the Islamist International by Mohammad Ataie

The book “The Fate of Third Worldism in the Middle East,” by examining these global and regional political changes, believes that the weakening of third-worldist movements can be traced back to the late 1970s. This period in various ways returns to the most common themes of today’s Middle Eastern political studies: consolidation of authoritarianism, rise of Islamism, decline of Arab nationalism, bifurcation of regional politics (between the normalization camp led by Egypt and Gulf countries versus the hostile camp led by Syria and Iran), the decline of Marxism, and the emergence of authoritarian-neoliberal powers centered around the Gulf countries.

In scholarship, the year 1979 has interpretive and analytical power as a watershed moment. Even at the time, observers flocked to Iran to witness the revolution unfold over the course of several portentous months in 1978–1979, most famously Michel Foucault, who recorded his observations for Corriere della Sera in the fall of 1978. With the passage of time, 1979 acquired an interpretative power that guided much of the political and intellectual historiography of that period.

In historians’ terms, it became truly an event, ‘a conceptual vehicle by means of which historians construct or analyse the contingency and temporal fatefulness of social life’. With the Iranian Revolution, the Egyptian–Israeli peace treaty, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the seizure of the Grand Mosque in Saudi Arabia, and other events outlined by Elling and Haugbolle in the introduction, 1979 became ‘the year that shaped the Middle East’, with all the violent connotations this entails.4 Its significance seeped into a wider interpretation of shifts in the region, including an intellectual and ideological shift from the radical left to radical Islam.

Iran, Zahedan city. Demonstrations after the victory of the 1979 revolution.

Social Movement or Rhetoric of Authoritarian States?

Based on the research in this book, the reason why echoes of third world ideas are entangled in the quasi-anti-imperialist rhetoric of authoritarian states with colonial and imperialist practices, and quasi-state forces clearly in conflict with the ideals of leftist third-worldism, should be explained in the context of the post-1979 shift in the Middle East.

The book demonstrates that in the early 1980s, Middle Eastern states co-opted and institutionalized the revolutionary spirit of third-worldism within authoritarian regimes. This continues today in the form of anti-imperialist rhetoric promoted by authoritarian governments. Therefore, Haugbolle and Elling believe that by the mid-1980s, the dominant expression of third-worldism was no longer in the form of social movements, transnational solidarities, and revolutionary ideas of dissident intellectuals, but primarily in the propaganda and rhetoric advanced by authoritarian regimes.

The discourse presented in this volume carries not just historical significance and scholarly value with reference to the historiography of the Global South, and leftist movements within the Middle East—specifically in Iran and Palestine—but also provides critical insight for contemporary global and regional leftist factions. These factions find themselves in a state of vacillation, grappling with the dilemma of whether to extend their support to ostensibly anti-Western and anti-imperialist governments, which paradoxically exhibit quasi-imperialist agendas on a regional level and uphold undemocratic frameworks domestically, or to champion the cause of radical democracy in direct opposition to these regimes.

Sure, there’s another thing we’ve gotta chew on: maybe what calls itself the ‘left’ in Western circles isn’t really all that left-wing. Might it just be a piece of the right-wing mentality in a clever disguise, acting all progressive while really just slinging around populist, hypocritical vibes?

The contributions in this book complicate the picture around 1979 in two important ways. First, they shed light on how informal networks stretched out on both sides of the 1979 divide. Second, and in relation to that, they complicate the conceptualisation of the relationship between, on the one hand, the leftism that characterised Third Worldism in the 1960s and 1970s, and, on the other hand, Islamism. The relationship between the two cannot be understood either as a linear development or as a clean break.

Between Iran and Palestine, there were ideological currents and activist networks that persisted after the Iranian Revolution, even as they transformed in the process. The period stretching up until 1982 saw a balancing act and a set of tensions between two political visions that co-existed on the political scene in the Middle East and had reverberations that extended beyond their nationalist descriptives: the Iranian Revolution and the Palestinian liberation movement.

The first was increasingly Islamist, the other remained leftist and secularist in orientation. Yet, while they seem irreconcilable on the level of big politics, the histories traced out in this volume shed light on the tensions as well as the dynamics between the two.

.

You can order the book from Oneworld Publications

Alternatively, you can read the book from Perlego.